A Possible Basis for International Accord After the War

The foreign policy of the UnitedStates is not a mysterious game, carried on by diplomats with other diplomats in foreign offices all over theworld. It is for us the task of focusing and giving effect in the worldoutside our borders to the will of onehundred thirty-five million peoplethrough the constitutional processeswhich govern our democracy.

—Cordell Hull

A N OPPORTUNITY for Education seems to be presenting itself. It is already activated by the present war effort: if examined now and proven sound, a plan may be developed and put into operation as soon as hostilities cease. It might be well to review certain affairs which reveal this opportunity and may prove an obligation of Education.

All the while since that Sunday morning attack on the territory of the United States at Pearl Harbor, we have been gearing industry to production feats that have passed all expectations. All the while, too, something has been stirring within the American people. New patterns are taking form in the national fabric of the country. We have learned, among other things, what is the meaning of Democracy. We have more and more a growing conviction that Democracy is the basic ideology of these United States. We are learning that it is not some physical formula for the construction of a government. It is an abstract objective, an ideal, to which we aspire as a nation. Democracy is, in essence, the soul of the American people. This truth is as tangible a national symbol as is the Rock of Plymouth, the Bell at Philadelphia, the Mission at San Juan Capistrano, and the Village at Williamsburg. It works itself out in such results as are typically American. It manifests itself in such fashions and char- acteristics as are denominated under the caption "The American Way of Life" or "The American Way of Doing Things." This could be one result of the working out, during all these years, of that first postulate in the Declaration of Independence-"All men are created equal" .... and are entitled to "Life, Liberty and the Pursuit of Happiness." This is the yeast which has leavened the whole structure of the United States.

The spirit of American democracy is sifting into the most remote corners of the earth. It is within the focus of American good-will to make the right to "Life, Liberty and the Pursuit of Happiness" available to all peoples in all countries. During the past years, this theme has often been enunciated by statesman, preacher, politician and teacher. Now the time seems ripe to stop generalizing and talking platitudes and to evolve and establish a definite plan of action. American stock in world markets (except Berlin and Tokyo) is high right now. It is the better part of wisdom to cash in on this situation. This idea was forcibly called to the writer's attention by a revealing experience.

One evening in Cairo last year, he happened to notice, not far from Shepheard's, three different movie houses. In front of one of them, a large poster, in Arabic and garishly illustrated, advertised the beau and belle of Egypt. Not a customer was seen to buy a ticket at the admission window. Less than a block away, another theatre was showing a French film. A few people bought tickets for this show. On the other corner, a third cinema was showing a recent Hollywood headliner with the usual "all-star" cast. The crowd of people waiting to buy admission formed a queue that trailed along the sidewalk and into the street in rows. The sound sequence was in the same American language as played on Broadway. The audience, consisting, besides the native Egyptians, of Poles, Greeks, Palestinians and French, as well as all allies in uniform, "didn't miss a trick or a wise crack." The gist of the story was flashed concurrently in Arabic, Greek and French on separate boxes to the right and under the screen. Nevertheless, no one was heard to read aloud the foreign captions as children are apt to do—and there were plenty of children, also. American pictures are so much more sumptuous than all the others that even the little Arab urchin waits to beg a few piastres more so that he can get in to see the American film. The same situation exists throughout the Middle East as well as North Africa. All the world, it seems, is learning the American language, and wherever you go natives want to talk about America, expressing their wish to go there sometime soon. A charming French friend of the writer remarked to him one afternoon at a Sunday tea, "French as the diplomatic language must give way to the American language: moil pauvre francais can't stand this competition."

We, as a people, however, must be alert, shrewd, and not lulled into a false state of mind by this and many other similar conditions. Right now it seems to me we are assuming an attitude before the world that is fraught with danger. Further, it appears that the great majority of our people have not the slightest idea of the situation. We do not stop to think that the rest of the world might be different from us and the danger lies in just that fact—that the rest of the world, except for the cousins of ours in the British empire, is entirely different.

The situation is comparable to the preMunich days and the status identically that which so cruelly disillusioned Mr. Chamberlain. His was the school of culture, typical of the genteel Englishman and his distinguishing good manners. He believed in decency and he approached Hitler on that high level. There, however, he encountered only Teutonic arrogance, diplomatic checkmate and the stacked cards of War. Now, on this side, there isn't a thinking American today but what is grateful for our national prosperity and political largesse d'esprit. Because of it, we can conceive an Atlantic Charter and enunciate the doctrine of the Four Freedoms. If all the other countries had this same comprehension, we could expect to see comparable results manifested in the daily lives of their peoples. Such is not the case, desire it as we would. We cannot thrust our God-given but precept-earned heritage upon them. We can be idealistic but we must be realistic too. Therefore we must see just how diametrically opposite to us are other peoples of the world, their governments histories and places. We must stop assuming that all other nations have standards the same as ours. We have been naive in this assumption and our effectiveness in diplomacy will be limited unless we mend our ways at once. We have got to know our neighbors, learn about them, understand them.

MUST KNOW OUR NEIGHBORS

Our neighbors want to buy our goods; they are learning our language and seeking to come here to live. They are learning much about these United States and incidentally are absorbing somewhat the spirit of Democracy. But there is a corollary to this situation. It is incumbent upon us to know our neighbor. This is essential if we are to arrive at a mutual understanding. This is the first requisite in writing a foreign treaty, in formulating a foreign policy, and in furthering the interests of world peace. Times were never more favorable than right now to undertake the study and discovery of our neighbor. We are sending many millions of our soldiers and sailors, both male and female, all over the world. Contrast this, with two million during the War of 1914-18, in which troops gathered mostly in France. Our returning forces will be able to tell us what are sortie of the things that must be done and they will be able to help us do them.

There has already been discussion in government circles on the subject of post- war education for these veterans. Now is not too early to consider a concrete plan to implement such a program and to enlist interest in its support. Building mutual understanding between two nations is to erect a bridge leading from our homes to their homes. Upon crossing it, what a pleasure to receive a cordial welcome on the other side!

Let us consider the merits of a plan o£ "Exchange Education"—a plan to exchange qualified students of university age with those in comparable universities in other countries. This idea is not new but rather has occupied the interest and thoughts of many educators in the past. It has remained only in the theoretical stage because the program lacked an earnest of fulfillment and the necessary financial support to put it into effect. A sound plan of exchange education, inaugurated by the time hostilities cease and sponsored and directed by an authoritative agency, will anticipate an opportunity to foster mutual understanding in international affairs.

CURRICULUM A JOINT EFFORT

It isn't the intention here to outline a curriculum in a definite plan of operation. One person cannot do it. It must be the result of the work of experienced educators. The pooled judgment of selected diplomats, Army and Navy heads, international news agencies, international business executives, and competent educational leaders will be necessary to insure its success.

Adequate coverage should not be over- looked. A group of qualified veterans would be placed in each reputable university in each of the leading countries of the world. Under no circumstances should this plan be interpreted as an opportunity for military espionage. Each foreign government should endorse this plan without reservation, otherwise our college groups in that country could not accomplish their purpose. Each student group must be above suspicion, in order that it may cultivate the spirit of personal friendship which is the foundation both countries are to build by mutual effort.

It would be expected that after veterans complete their studies in foreign countries they would return home. In like manner, students of foreign countries, here in the United States on an exchange basis, would return to their countries when their studies were ended. This is. to prevent their adopting the new country, becoming naturalized and defeating the objective of this plan. Adequate coverage of countries and colleges in each country is desirable. Not only would our leading colleges admit qualified foreign students but we would place our students according to the policy based upon immediate and near-future conditions. For example, right now it would appear desirable to send these prospective students to study in the universities of Russia, China, India and the Near East just as soon as conditions and plants permit. In like manner, we should arrange to solicit students from these foreign countries and place them in American colleges of their choice if they have any. In lieu of preference, we would endeavor to anticipate what the country of each might wish to accomplish from this exchange and accommodate accordingly.

Important questions are bound to arise involving these countries noted above. There are by no means too many Americans who may be considered experts on these countries. Now is when we need them and they are missing. Short-range as well as long-range planning in this program is as necessary as in government or business. Exchange education should be regarded as an investment in American citizenship; its dividends will be the expert services to this country that the recipients of the plan will render in the future. In like manner, the foreign personnel, after returning home, will the more ably interpret the United States to their compatriots. This would appear a practical method of fostering mutual understanding based upon mutual respect and individual friendships. This program, inaugurated as soon as possible, would fill the hiatus between war and peace economies and place a considerable number of veterans in the most valuable kind of "jobs" when fighting stops. This will, in a measure, ease military discharges and contribute to the general preparation for world leadership that the United States must assert after this war. We cannot shirk this responsibility as we did in 1919.

We have nearly eradicated Fascism. We have dedicated ourselves to destroy unconditionally German Nazism and Pan-Japanism. We take more and more confidence in those policies which are building a Pan-American amity. We have arrived at the sober conviction that the more governments there are on earth like that of the United States, the safer will be the continuity and progress of our country. Like begets like and a sense of security is increased by numbers. So long as the American Way of Life follows a policy of precept and not one of coercion, then we can expect progress. Our government and our country are the example, and it is up to us whether or not other countries adopt and work out their concepts of Democracy following our pattern so that their fruits are of the same quality as ours. With the need for improvement in our own country so great, how much more can we be patient with our neighbors and how much more can we be ready to lend a hand! The establishment of perpetual world peace is the "work of eternity" and mutual understanding between nations is the foundation of that peaceful world. Exchange education seems to be a sound institution for fostering mutual understanding among participating countries.

COMDR. JOHN H. CHIPMAN '19, USNR, who outlines in this article the case for exchange education in the postwar world.

A varied business career and as varied a sfervice career in this and the last war quality Commander Chipman as an experienced and sympathetic sharer of the other fellow's point of view. Since going on active duty in the U. S. Naval Reserve-, he has been assigned to foreign and domestic service, has -served as liaison officer to the French North African Naval Mission, and is now stationed at Headquarters, Bth Naval District, New Orleans. In the last war he was overseas with the American Red Cross, American Field Service, and as Lieutenant in the French Foreign Legion, winning the Croix de Guerre and other decorations. He has been in the advertising, book publishing, and food purveying businesses, and served as 1919's class secretary from 1923 to 1924.

COMMANDER, USNR

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Article

ArticlePLANS FOR SERVICEMEN

November 1944 By WM. STUART MESSER -

Lettter from the Editor

Lettter from the EditorLetters from Dartmouth Men in the Armed Forces

November 1944 -

Class Notes

Class Notes1934

November 1944 By WILLIAM C. EMBRY -

Class Notes

Class Notes1918

November 1944 By ERNEST H. EARLEY, DONALD L. BARR -

Class Notes

Class Notes1933

November 1944 By GEORGE F. THERIAULT, LEE W. ECKELS -

Class Notes

Class Notes1917

November 1944 By MOTT D. BROWN JR., DONALD BROOKS

JOHN H. CHIPMAN '19

Article

-

Article

ArticleA Wah Hoo Wah for

OCTOBER 1962 -

Article

ArticleC AMPU S CO NFIDENTIAL

SEPTEMBER | OCTOBER 2015 -

Article

ArticleTAXI? CALL JOHN CASSIN '94

May 1940 By Herbert F. West '22 -

Article

ArticleThe Big Day

July/Aug 2003 By Julie Shane '99 -

Article

ArticleFIVE ADDLED ETCHERS.

DECEMBER 1969 By PETER D. SMITH -

Article

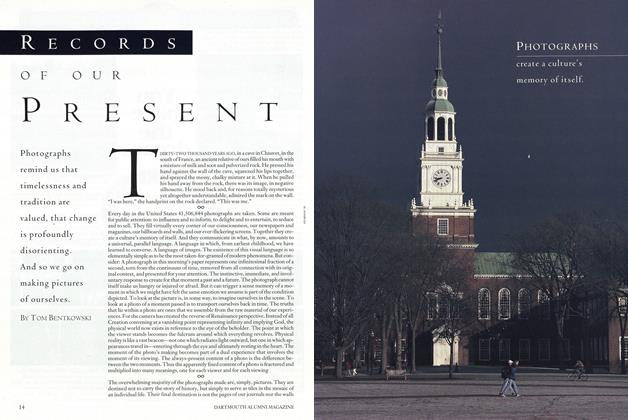

ArticleRecord of Our Present

JUNE 1999 By Tom Bentkowski