A Music Review

DARTMOUTH made music in Boston Town on the night of March 23, 1966. Werner Janssen '21 flew from his present home in Munich, West Germany, to hear the premiere of his latest composition, Quintet for 10 Instruments. This work was commissioned by the Harvard Musical Association and was performed from manuscript at the annual Award Concert in the club rooms, 54A Chestnut Street, Boston.

The conventional string quartet was augmented by an exceptional artist who supplied the music Janssen's score required from the piccolo, flute, alto flute, saxophone, Bb clarinet, and bass clarinet. George Humphrey, violist with the Boston Symphony Orchestra, organized this concert and obtained Richard Johnson, Mr. Five of the quintet, to operate the wind instruments. Mr. Johnson was required during the performance to switch from one instrument to another, sometimes with only a slight pause - a decidedly difficult feat to perform expertly. And, in the first performance of this extraordinarily unique work, he performed masterfully.

When Mr. Humphrey first received the manuscript from Janssen he recognized that finding this fifth performer might be the equivalent of looking for the needle in the haymow. Fellow musicians on woodwind instruments in Boston agreed there was just one artist in New England to do this job. Humphrey luckily located Johnson and found him free to rehearse and assist at the performance.

Quintet for 10 Instruments is programmed under the four conventional tempi: (1) Lento sustenuto, (2) Lively, gay, (3) Relaxed blues, (4) Allegro. However, Janssen gave the four movements his own descriptive tags: (1) Theme in search of an instrument, (2) More searching (no break between 1 & 2), (3) Obsequies of a Saxophone, (4) The REST IN PIECES. Publication of the manuscript is presently under consideration.

This Quintet is modern, classical chamber music. It is refreshing in its originality, construction, and musical idiom. To Werner's friends at Dartmouth it is truly thrilling. He is so inseparable from his work that those who know him can see hints of the sophomore at Dartmouth who has become the mature musician of today.

The first reading of the manuscript reveals the music to be as complicated as the dense tonal forests of Hindemith, Bartok or Schoenberg. At times, the rhythms are frantic. A few measures in 7/8 tempo leap into 5/4: after a few bars of 12/8 then you find the strings competing among themselves, the violins at 3/4 and the lower strings at 4/4. These jockey simultaneously with the woodwind speaking a dominant theme. Add to this the complexity of strains at pianissimo, suddenly bursting into a flame of dissonance at double forte, and you wonder if you are hearing correctly. At times it is soothing to see the bows of the quartet weaving in unison at an easy tempo; then, suddenly to break, each instrument going its own way. Your eye becomes as fascinated as your ear. Things happen so fast, you have to admit that you grasped, at the end of the work, only a fraction of what your ear heard but did not successfully register on the brain. You want to hear this Quintet again and again.

How to describe adequately this most original new work? Let George Humphrey, the violist, a musical scholar of the first rank, give you his impressions as they crystallized during practice and performance, which required 27 rehearsals to prepare:

"Hardly knowing Werner Janssen personally, except for two brief meetings I have gotten to know him well as a result of studying and practicing his music for this concert. I was at first struck by the idiom he was using. It was unique and most interesting, in fact dynamic. Its style appeals to me tremendously because my particular musical kama took form during the melodious years of 1910-1925. Janssen and I are contemporaries. His 'atmosphere' recalls so graphically the best musical times of my life. It brings back to memory my younger days in my home town in Ohio when I first discovered the spell of beautiful music. The nostalgia of Janssen's music is a warming experience. As we practiced our parts, I felt strongly the sentiments he was putting into his music and I began to hear the tones and overtones of his musical significance. The more we worked on the Quintet - and it is a difficult composition to play well and as intended - the more I was convinced of one fact. Janssen knew well the contemporary technique of composition. He builds upon more solid ground than most composers today. He has created fetching melodies. Most modern music lacks them and for that reason has little basis for being composed at all. Janssen's melodies are surprising and original. None brings to mind any contemporary music. Yet, they spark the memory of the wonderful days of yesterday.

"Without this knowledge of native American music of yesterday, youthful musicians today have no tangible background to aid them to build an American music of tomorrow with a natural continuity. I wish I could say that Janssen's music might be instrumental in swinging the pendulum this way. We definitely need composers who can write such music. Sadly, the present generation, not acquainted with or deeply feeling and sensing these sentiments, is unable to recognize or accept what Janssen is saying. But those of the adult generations should be able immediately to hear and feel them. But this is not to indicate that Janssen's music is old-fashioned. Any musician will affirm that Janssen knows what he is doing musically. His own identifiable idiom is in a completely modern, classical manner. Undoubtedly he knows whatever 'tricks' are in most composers' bags, but in Quintet for 10Instruments he does not resort to them nor does he have to. In fact, I doubt if he would ever stoop to use effects just for effect's sake. His innate talent to write and delineate his innermost musical thoughts precludes that temptation. Perhaps his idiom might become with time the 'missing link' between yesterday's music and tomorrow's. I have not described all that could be or should be written about this Quintet. Language lacks the vocabulary to describe the thoughts which remain inside me."

Modern music is having a hard time. Some composers, undeniably fine musicians, are so far above the heads of John Public that their music must remain music for professional musicians only. However, one with little technical knowledge of composition and harmony has to admit that hearing the Quintet for the first time is a real musical adventure.

As a freshman at Dartmouth, Janssen composed the music for the Winter Carnival show Heave To, with book and lyrics by Thomas Groves '18. Restricted by the limitations of World War I, it was a great hit for the times. For the next Carnival show, in 1919, he wrote the music and score for Oh, Doctor! The book and some lyrics were written by Gene Markey 'lB, Admiral (Ret.) USNR, Hollywood producer of several successful movies, author of many novels, and now squire of Calumet Farm, Lexington, the stable of some of the finest race horses in the world. Other lyrics were composed by Groves and Edward M. Curtis '20. Dartmouth bred top-flight ability even in those days.

Oh, Doctor! had the distinction in 1919-1920 of being one of the best musical comedies written by undergraduates for a college production. Its nearest competitor was The Fair Co-ed given at Purdue in 1909, starring Howard Marsh {Show Boat 1924), lyrics by George Ade and score and music by Gustav Luders (The Prince of Pilsen). Elsie Janis discovered this show at Purdue, recognized it as a fitting stage vehicle for her, took it to Broadway, and it became a hit, running for 136 consecutive performances. During 1919 Broadway was overstocked with good musicals and the competition was too strong for Oh, Doctor!

After graduation from Dartmouth in June 1921, Janssen headed for Leipzig to begin a rigid musical education. He completed it with distinction back home at Juilliard with additional private tutors. Naturally he veered toward Broadway and his first compositions were popular songs in the vein of the postwar period. The Ziegfeld Follies of 1925 included three of his hits, words by the successful lyricist Gene Buck. His best hit, "Toddle Along," is still remembered. Janssen was in the best of musical company at that time. "Jerry" Kern, one of Werner's best friends, was reaping huge royalties from Broadway's musical block-buster, Sunny, a sparkling circus show with Marilyn Miller. Cole Porter's musics star was nearing its zenith, popularitand prestige accumulating from his hit; in the Greenwich Village Follies. Jam sen found himself in the midst of wh2is now known as the Golden Age c Melody in America. In this milieu, Jans sen's musical idioms first came into be ing. He had the opportunity to learn how his musical concepts could be instrumentally achieved, how he could fashion the instruments in his orchestras to product the effects in his mind. Thus he knew what were sound potentials as well as natural limitations. He wrote his musical ideas with speed and accuracy and composed his own scores. During the time spent on Broadway he learned how to fit his music into the plan of the musical comedy which indicates a natural knowledge and feel for theatre. One ironic note might be mentioned here. For his production of Oh, Doctor! he refused to conduct the orchestra. He compromised by playing the piano in the orchestra. He always says, "I am a shy guy."

After his "stretch" on Broadway, the conductor's baton lured him away from composition except for those rare occasions when his genius burned and forced him to take up his pen. Fortunately, it did from time to time. His New Year'sEve in New York won for him the Prix de Rome in 1930. It makes a nice companion piece, in my opinion, to another fine, typically American work, George Gershwin's American in Paris, made unforgettable by Gene Kelly's interpretive dancing.

Werner Janssen began to command a masterful control of symphonic orchestra leadership. He admits the years he spent with the New York Philharmonic Orchestra under the tutelage of Arturo Toscanini were inspiring and priceless in spite of the discipline and rigorous regimen. He grants the old maestro gave him much fatherly guidance and actually opened the celestial gates of symphonic music. Werner Janssen was an apt and talented pupil. He was humble and teachable. His thirst for music was never satiated and his progress in conducting was early rewarded.

When his "apprenticeship" with the Philharmonic was completed, he began a succession of leadership of many fine orchestras. Most of them he had to build from the ground up and was given the opportunity to do so without restrictions because of executive confidence in his ability to construct a complete symphonic instrument. Among these orchestras were: Baltimore, Salt Lake City, N.B.C., and later his own in Hollywood. He was soon called to Europe where he drilled and conducted fine orchestras in Austria, Germany, Italy, and Finland. He gave to each organization a new approach to the classics, resulting in a freshness and enthusiastic interpretation which only a young American could provide.

One of the great historical musical events took place in Helsinki a few years ago when the National Orchestra within the space of one week performed all the works of Jean Sibelius with the distinouished composer present in the seat of honor. The week was declared a national holiday throughout Finland. The musical world was present in toto.

When Sibelius was asked what conductor he wished to perform his works, after he had declined to do so, he replied, "I want Werner Janssen." Critics stated that probably there had never been a more magnificent musical tribute paid anywhere in the world. The tribute to Janssen by the great master, after the week was ended, was affectionate and most complimentary and American music circles can take much pride in this accomplishment by one of their own. Janssen earned and retained the musical respect and personal friendship of all the conductors in his acquaintance.. Serge Koussevitsky was one of his particular friends and in many letters from the great maestro of the Boston Symphony Orchestra, he expressed the hope on several occasions that Werner Janssen would return home and follow in his footsteps on the same podium.

The last outstanding achievement Janssen contributed to Europe (eventually to show in America) is the exciting and artistic movie in superlative color and costume, Robin Hood. For the production he composed in all 27 songs, the entire musical score, and conducted the orchestra for the final take of the picture. The premiere ran in two parts for two successive programs on TV in Europe on April 21 and 22, 1966. When it is ultimately viewed in America, it will add another "first" to American musical achievement. It is due to appear here this fall, possibly sooner.

Time magazine wrote a few years ago that there were three American musicians - Leonard Bernstein, Werner Janssen, and Alfred Wallenstein. A leading music publisher in New York and a good friend remarked, "He has been too long out of this country. He should come home and put on manuscript the wealth of genuine Americana pent up in his genius." Let us have this music, whether written in America or with our friends abroad!

Werner Janssen '21

Mr. Chipman, who lives in Norwell,Mass., is a businessman who has had alifelong interest in music. His book, Index to Top-Hit Tunes (1900-1950), witha foreword by Arthur Fiedler, was publishedin 1962.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

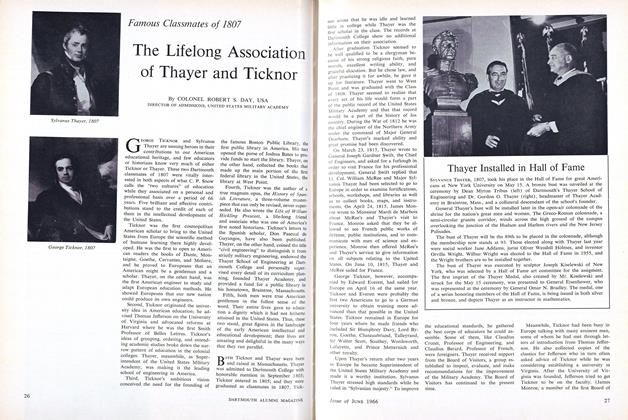

FeatureThe Lifelong Association of Thayer and Ticknor

June 1966 By COLONEL ROBERT S. DAY, USA -

Feature

FeatureRETIRING FACULTY

June 1966 -

Feature

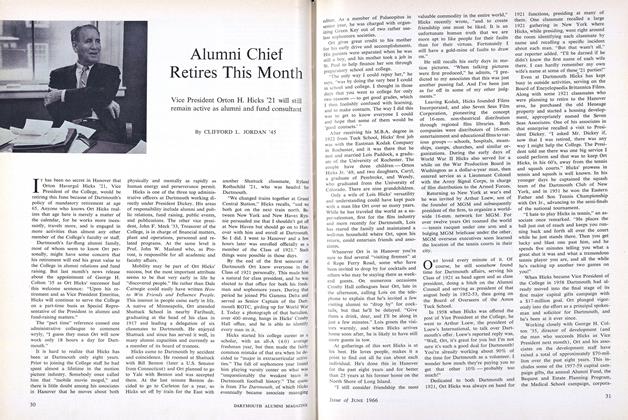

FeatureAlumni Chief Retires This Month

June 1966 By CLIFFORD L. JORDAN '45 -

Feature

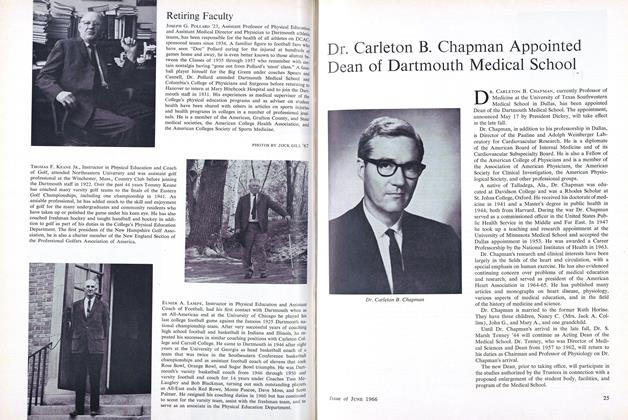

FeatureDr. Carleton B. Chapman Appointed Dean of Dartmouth Medical School

June 1966 -

Article

ArticleWith the Big Green Teams

June 1966 By PETE GOLENBOCK '67 -

Class Notes

Class Notes1932

June 1966 By JILDO CAPPIO, ALBERT C. BONCUTTER