Course Typifies College Adaptation to Navy Needs

V-12 HAS CHANGED the appearance of much of Dartmouth. English 1 and a have become E 1 and E 2, the shortening in the name being something like the changes in the courses.

Almost a year ago we began to plan, guided by the Navy's statement of purposes for the basic course in English. We found that we were to attempt to give four kinds of training: in reading, writing, speaking, and listening. We were also to devote some attention to American subject matter and "to extend the student's experience." It was not enough, however, to have these directions pointed out to us, for we had to move in partial darkness because we did not know what kind of students the Navy would send. We guessed what they would be like, and our guesses were not so far wrong that our plans had to be scrapped. We have made a few changes since work started in July, but the description that follows will probably fit E 1 and E 2 for the duration.

In both E 1 and E 2 there are three class hours a week, two in English and one in Public Speaking. Sections remain intact, but there are different instructors for the two subjects. Naturally, in both English and Public Speaking, we feel pressed for time; thirty hours of classroom instruction in Public Speaking during a year, and about sixty in English do not equal the eighty hours or more that either subject would have in a civilian course.

EXPRESSION COMES FIRST

In the English part of E i we devote the first five or six weeks to intensive training in clear and correct expression in writing. The first theme, as for ages past, is the student's autobiography; it is followed by the writing of definitions, of a paper on how to perform some simple (or difficult) action such as abandoning ship, another on how a mechanism is constructed or operates, the writing of paraphrases and prdcis (this gives training in both reading and writing), and the composition of Naval letters and reports. This last is part of the work on Naval correspondence, in which a student learns, among other things, when and when not to begin a letter with a "from" line, how to route a letter,-how to request a change of duty, and how to present a report. He is asked to read, for example, Ira Wolfert's eye-witness account of the Fifth Battle of the Solomons and, assuming that he was present, to write a report on the action for his superior officer.

In E 1 a student reads much of a textbook called Models in Semi-T ethnical Exposition, which contains such semi-official articles as those on "leadership" and on "How to Use Your Eyes at Night," Fletcher Pratt's "Campaign in the Coral Sea," Lieutenant Brodie's "War at Sea," and others less thrilling but equally practical or technical.

When he comes to E 2, the student, who by this time has been trained to write with at least passable correctness, is more free to choose his own subjects for themes. He finds himself in a more cultural course. It is here that -we extend his experience. He reads Churchill's Blood, Sweat, andTears and learns more than he knew before about that great leader, about the early history of the war, about what constitutes fine oratory. Then he comes back across the Atlantic and in an anthology of American poetry is shown that many poets have expressed much of the spirit of his country. Finally, he reads Conrad's Lord Jim, a novel almost sure to interest any young man, especially a Naval trainee.

That is an outline of our subject matter in the English part of E 1 and E 2. It fails to reveal the actual teaching process, which consists of recitations, quizzes, and discussions in sections averaging about sixteen students. They are serious, more so than civilians; they work harder. They come to us with less preparation in English and therefore need more careful coaching, which is given to them in class, in comments written on their themes, and in private conferences.

Supplementary to the work in English is that in Public Speaking, planned by the Public Speaking teachers and ably administered by Professor George V. Bohman. The small sections in E 1 and E 2 make it possible for each student to speak frequently, a practice of great importance in early training. He is taught to appear at ease before an audience, to use his voice and to arrange his material clearly, to catch and hold the interest of his audience, and to listen attentively and intelligently.

Various special exercises impress students with the practical value of the work in Public Speaking. A trainee is taught how to shout orders without straining his voice; he hears one of his speeches repeated to him by a phonograph record which shows him his faults; he practises both giving and receiving orders over the intercommunicator or "squawk-box" system in Wentworth. In this exercise, students in one classroom practise speaking against a background of highly distracting noises to students in another room who also have to concentrate on what is being said and to ignore the sounds of swishing waves, airplane motors idling, machine guns firing, and bombs exploding, all realistically reproduced.

Because a Naval officer has often to instruct enlisted men, trainees are assigned group projects in which they discuss a problem. For example, each member of a class is told that he is Personnel Officer of the USS BROOKLYN. His Executive Officer has assigned him the task of teaching Recognition to a contingent of fifty Seamen z/c-' fresh from boot camp. In class, each student takes part in a discussion of what material on Recognition should be presented in a forty-minute lecture, how the material should be organized, how the Seamen can be interested and made to remember what is said, what visual aids should be used, and other problems.

The courses I have described do not sound like the old English 1 and 2. Fundamentally, however, the English work resembles that of peace time: it aims to teach clear and correct writing and intelligent reading, to give a slight and brief introduction to some forms of literary expression, and to inculcate a taste for good literature. In short, it is both practical and cultural. The work-in Public Speaking, more immediately practical, develops the student's ability to use his voice, his body, and his mind to the best advantage. E 1 and E 2 provide one illustration of how Dartmouth has adapted herself to serving the needs of prospective Naval officers.

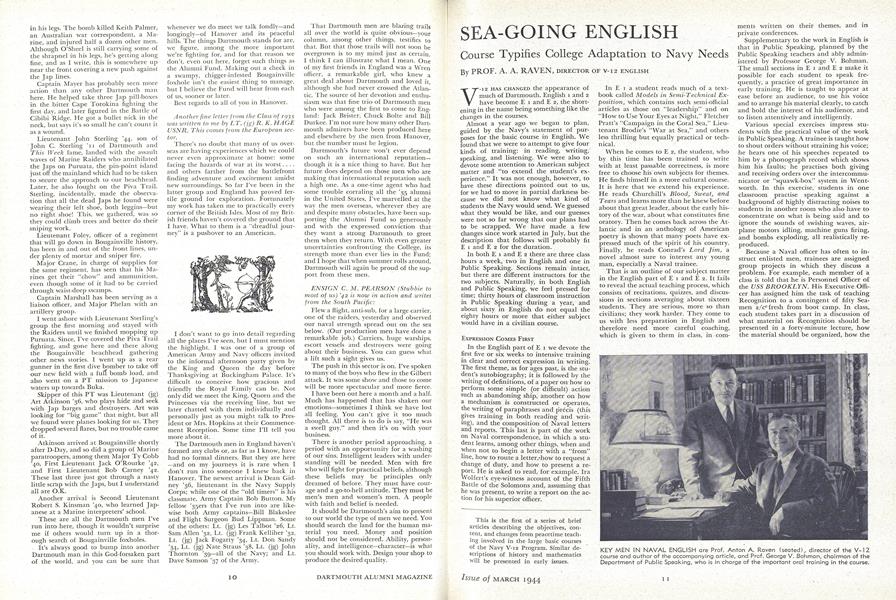

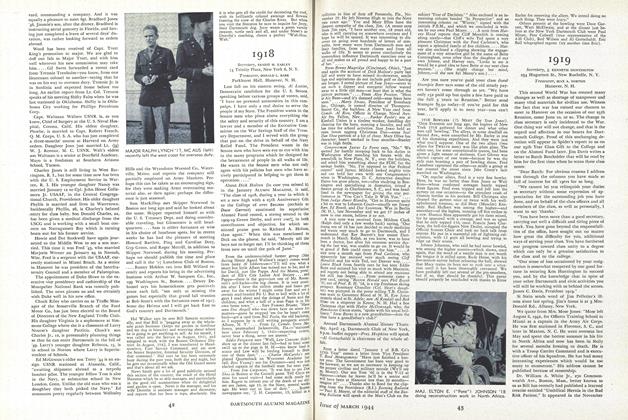

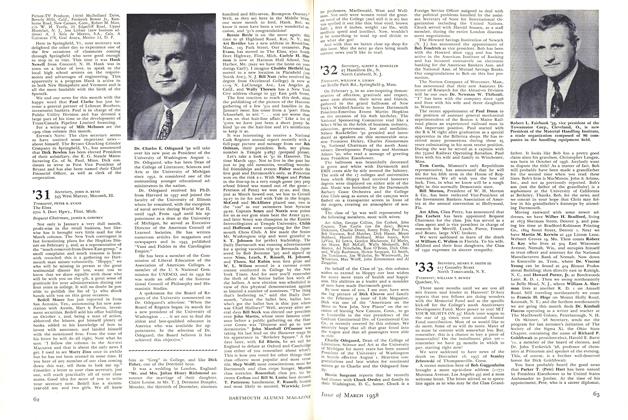

KEY MEN IN NAVAL ENGLISH are Prof. Anton A. Raven (seated), director of the V-12 course and author of the accompanying article, and Prof. George V. Bohman, chairman of the Department of Public Speaking, who is in charge of the important oral training in the course.

DIRECTOR OF V-12 ENGLISH

This is the first of a series of brief articles describing the objectives, content, and changes from peacetime teaching involved in the large basic courses of the Navy V-12 Program. Similar descriptions of history and mathematics will be presented in early issues.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Article

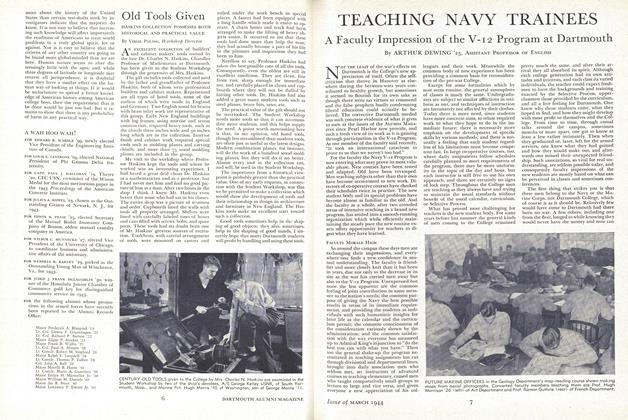

ArticleTEACHING NAVY TRAINEES

March 1944 By ARTHUR DEWING '25 -

Sports

SportsWith Big Green Teams

March 1944 By Dick Gilman '45 -

Class Notes

Class Notes1918

March 1944 By ERNEST H. EARLEY, DONALD L. BARR -

Class Notes

Class Notes1931

March 1944 By CHARLES S. MCALLISTER, WILLIAM A. GEIGER -

Lettter from the Editor

Lettter from the Editor'Round the Girdled Earth

March 1944 -

Article

ArticleARTHUR FAIRBANKS '86

March 1944 By DR. FREDERIC P. LORD '98

Article

-

Article

ArticleENGLISH DEPARTMENT INSISTS ON STRICT REQUIREMENTS

May, 1924 -

Article

ArticleDr. Charles E. Odegaard '32 will take

March 1958 -

Article

ArticleClass of 1967

Jan/Feb 2007 By Bonnie Barber -

Article

ArticleNo Ivory Tower on Costs Either

June 1946 By C. E. W. -

Article

ArticleREAD WORTHY

May/June 2007 By Carolyn Kylstra ’08 -

Article

ArticleTHE FOOTBALL RULES

DECEMBER 1905 By F.G. Folsom '95