Inflexible Requirements of Wartime Training Programs Induce Students to Give Deeper Thought to Liberal Arts

A MAN'S THINKING ABOUT liberal education in the postwar world is ofte clouded these days by concerns which college catalogues generally grouped under the heading "Social Life" rather than those which appeared under "Courses of Study." The sight of a fast, shiny convertible, or a girl playing tennis in the sun, or sailboats on a lake, are not conducive to thoughtful meditation on the objectives of college education after the war. And yet, the question remains. The kind of upheaval we are going through now leaves no aspect of our life immune from re-examination, and the experience we're having with going to college in wartime has excited among students more interest in the nature of higher education than ever seemed to exist when we were civilians.

The war has properly caused a revolution in our curriculum. The urgent need for technically trained men must come before anything else. Most of the men who are studying here now are taking courses which in peacetime they might never have considered. They are working hard on fully prescribed programs which very often contain as many courses they dislike as they like, because it is necessary to win the war, and right now nothing else counts. It's pretty hard for a great many of the men who are in these courses. Liberal education at Dartmouth has by no means closed up for the duration. Side by side with men taking full technical courses, some others are still attempting to get a liberal education.

Men who are wholly absorbed in the intricacies of descriptive geometry, heatpower engineering, and spherical geometry, may have roommates who are able to elect several courses from the regular curriculum. The effect of this kind of experience is to give practically everyone an overwhelming desire for freedom of choice in education.

This desire manifests itself in many ways. The news of proposals to offer veterans a free year of education was not received with the unanimous acclaim which on the surface it would seem to merit. While very few of us would dispute the rationality of government financial aid to those who need it, the extent to which the government would control the courses we took is a real concern. But it does seem that the colleges themselves are fully aware of this kind of danger, and that the government will probably be working with the colleges and not against them when the time for administration of laws promoting veterans' education comes around. However, what seems to many men to be another threat comes right from institutions of education in many parts of the country.

Our ideas of what constitutes "liberal education" vary between widely ranged extremes. One segment of thought seems to hold that the only well-educated man is one who has read and discussed a certain number of specified books, omitting not one, nor including any other. A little bit, but not very far, to what one might call the "left" side of this opinion, is that which holds for the re-constitution of the one "true university," where in the tradition of the medieval university we are told the fundamental things we must know and then proceed to learn them as directed on the box. The pendulum swings in the opposite direction too, and there are proponents of a wholly elective system which seems to bring the college and the progressive nursery school very close together. The theory here being that if little Willie's fondest wish is to hurl mud-cakes at sister Suzie, he'll be best educated by being permitted to fling to his heart's content.

To the average student who hasn't thought very much about theories of education, it seems that any of these schemes, if wisely carried out, may have equally good results. But most of us who return to college after the war will probably be taking a middle way in education. And it seems important to us now that the inflexibilities of the wartime curriculum should not be permitted to have an undue influence on postwar education. We don't have to train warriors in peacetime. If we can judge from the men who are leading us now, most of them were men who did not have specific technical training for the jobs they hold, but whose education fitted their minds for the kind of training which was necessary when the emergency came. The middle road which we take should be slanted toward freedom rather than toward restriction. If a man appreciates his subjects and his teachers, he will be educated. When more restrictions are applied, the chances of prescribed courses and teachers coinciding with the needs of individual students become more remote, and men of real liberal education are only accidental products of the system. A man must be permitted to seek and find his own best education. He'll need a good library, good teachers, and good counsel, but where the goal is discovery of one's self and one's relation to the world, rather than a mastery of mechanical ideas, over-direction is almost as bad as no direction at all.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Article

ArticleTHE GREEN FLIES HIGH

May 1944 By ARTHUR SAMPSON -

Class Notes

Class Notes1914

May 1944 By DR. WALLACE H. DRAKE, JOHN F. CONNERS -

Lettter from the Editor

Lettter from the Editor'Round the Girdled Earth

May 1944 -

Class Notes

Class Notes1917

May 1944 By MOTT D. BROWN JR., DONALD BROOKS -

Class Notes

Class Notes1934

May 1944 By WILLIAM C. EMBRY -

Class Notes

Class Notes1918

May 1944 By ERNEST H. EARLEY, DONALD L. BARR

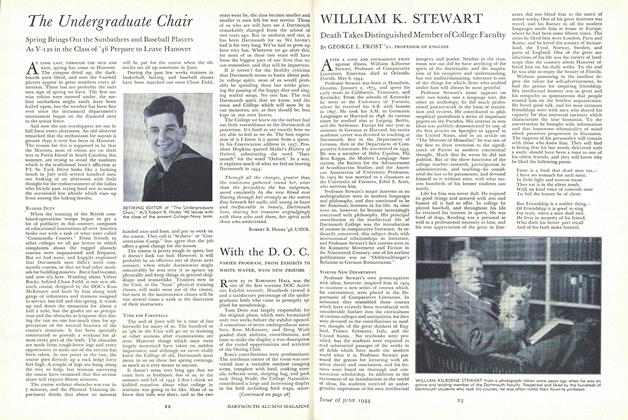

Robert B. Hodes '46, USNR

-

Article

ArticleSOME CAN DO IT

January 1944 By Robert B. Hodes '46, USNR -

Article

ArticleMILESTONES:

January 1944 By Robert B. Hodes '46, USNR -

Article

ArticlePARADISE FOR ESCAPISTS

March 1944 By Robert B. Hodes '46, USNR -

Article

ArticleFEBRUARY EXODUS

March 1944 By Robert B. Hodes '46, USNR -

Article

ArticleThe Undergraduate Chair

June 1944 By Robert B. Hodes '46, USNR -

Article

ArticleTIME FOR FAREWELLS

June 1944 By Robert B. Hodes '46, USNR

Article

-

Article

ArticleNORWICH OUTING CLUB TRAIL WILL CONNECT WITH D. O. C

November, 1922 -

Article

ArticleALUMNI HAVE CHANCE TO BECOME RESERVE OFFICERS

April, 1925 -

Article

ArticleFoundation & Corporate Relations

OCTOBER • 1987 -

Article

ArticleAn Honor for Fritz Alexander '47

SEPTEMBER 1988 By FRANCIS R. DRURY '48 -

Article

ArticleWith the Outing Club

June 1931 By N. E. Disque -

Article

Article"We Can't Take It"

November 1935 By The Editor