"When a person is confronted by offensive speech, the response of choice should be more speech."

LAST DECEMBER I WAS HONORED to accept the William O. Douglas First Amendment Freedom Award of the Anti-Defamation League. In accepting that award I spoke about Justice Douglas and the importance of the First Amendment to our nation. For William O. Douglas, First Amendment rights enjoyed a preferred position in the constitutional pantheon of values. They were the rights that made all other rights possible. In scores of decisions, Justice Douglas insisted upon the free exchange of ideas as democracy's principal assurance of political freedom, intellectual vitality, individual dignity, and social diversity.

Justice Douglas would have understood that the increased diversity of our nation and our college campuses inevitably brings a certain amount of conflict—conflict that challenges our commitment to the values of the First Amendment and tests the appropriate limits of free speech. As much as any other Justice in the Court's history, Justice Douglas appreciated that the First Amendment was not intended to protect speech that is popular; such speech does not need protection. Indeed, he once wrote that "a function of free speech under our system of government is to invite dispute" and a consequence is to "stir people to anger." As he well understood, the First Amendment was intended to protect the very speech most likely to put tolerance and civility to the test.

Such a high respect for the values embodied in the First Amendment means that colleges and universities, public and private, must respond to speech that is hateful and loathsome in ways that preserve fully the values embodied in the First Amendment. It means that they must resist the expedient lure of disciplinary codes that would limit or chill with vague or overbroad prohibitions the freedom of expression of their students, however abrasive and obnoxious that expression might be.

But it does not mean that intimidation or harassment directed at individual students is acceptable. Nor does it mean that mean-spirited and repugnant rot must be left unanswered. The First Amendment does not require silence in the face of ethnic insult or passivity in the face of racial prejudice. Rather, it guarantees the right to speak out in response to the words of others just as fully as it protects their right to speak. When a person is confronted by offensive speech, the response of choice should be more speech.

Freedom of speech should be exercised vigorously, but with a self-discipline that respects those who hold opposing points of view and with a keen recognition that the pain of being assaulted by the vituperation of ignorant bigotry is profoundly real. My appeal at Dartmouth has been for tolerance and civility for reliance upon the quiet, measured force of reason and for what Learned Hand, a great conservative judge, described as "the spirit of liberty "—" the spirit which is not too sure that it is right."

As our nation becomes increasingly diverse, it needs even more dearly than before the full breadth of the freedoms guaranteed by the First Amendment, precisely because the voices most in need of public protection are those of minorities and of persons espousing unpopular positions.

The growing diversity of our nation and our campuses also requires a greater appreciation that speech most effectively serves its civic and educational purposes when individuals exercise their First Amendment rights with a humane sense of personal responsibility. Civil liberties flourish best in a social environment of civil attitudes.

Perhaps the most important vehicle for attaining true equality is freedom of speech and the values upon which it is based: a belief in the dignity of all individuals, a conviction that reason can lead toward greater understanding, and a faith that the human condition can be advanced.

The values enshrined in the First Amendment, even when free speech rights are exercised with passion, need not fracture our society; rather, those values offer the greatest promise of binding together the pluribi that form our unum a democratic nation of high promise, for ourselves and for the world.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

FeaturePARTYING: A PEER REVIEW

May 1992 By John Scalzi -

Cover Story

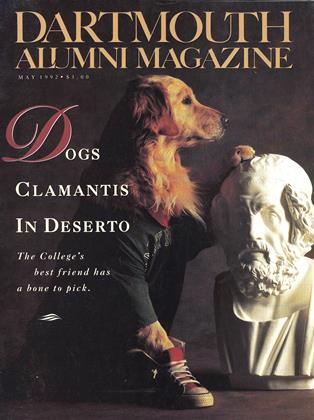

Cover StoryDogs Clamantis in Deserto

May 1992 -

Feature

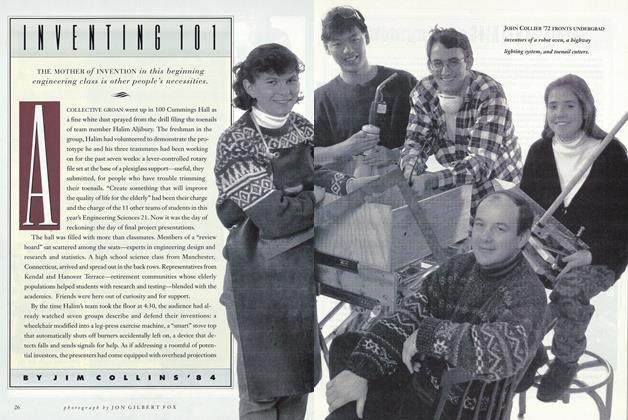

FeatureINVENTING 101

May 1992 By JIM COLLINS '84 -

Feature

FeatureOh, You Shouldn't Have!

May 1992 By JONATHAN DOUGLAS -

Cover Story

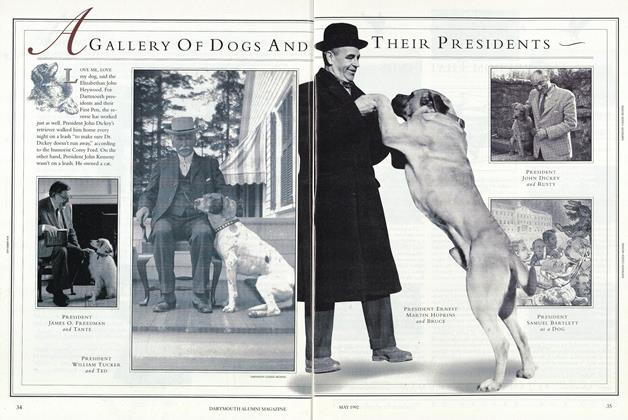

Cover StoryA Gallery Of Dogs And Their Presidents

May 1992 -

Article

ArticleIf Only it Ware Just a Myth

May 1992 By Professor Hans H. Penner

James O. Freedman

-

Cover Story

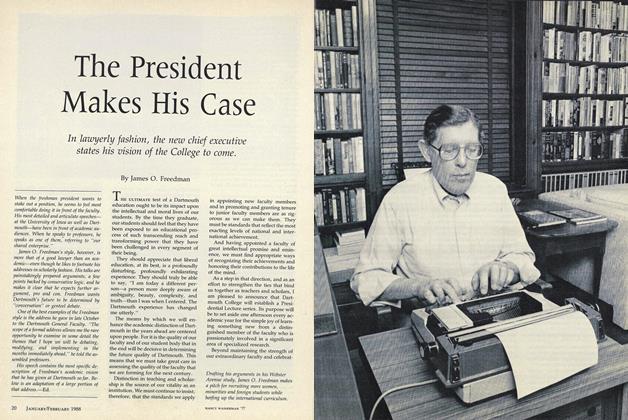

Cover StoryThe President Makes His Case

FEBRUARY • 1988 By James O. Freedman -

Article

ArticleTHE HEROIC OUTSIDER

December 1991 By James O. Freedman -

Article

ArticleCompared to What

June 1992 By JAMES O. FREEDMAN -

Article

ArticleThe Education Gap

January 1996 By James O. Freedman -

Article

ArticleThe Uncertain Future of Medical Education

DECEMBER 1997 By James O. Freedman -

Article

ArticleLibraries Unbound

JANUARY 1998 By James O. Freedman