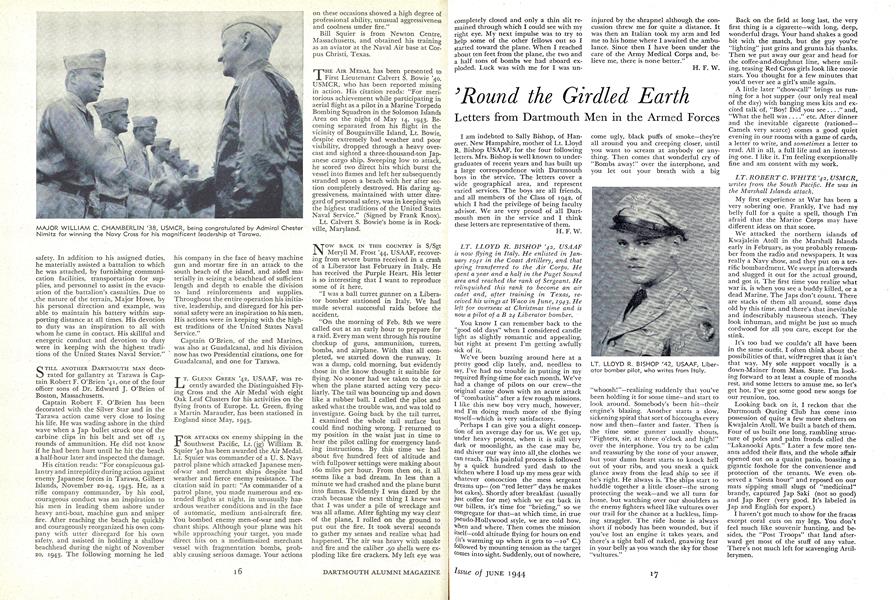

Letters from Dartmouth Men in the Armed Forces

I am indebted to Sally Bishop, of Hanover, New Hampshire, mother of Lt. Lloyd R. Bishop USAAF, for the four following letters. Mrs. Bishop is well known to undergraduates of recent years and has built up a large correspondence with Dartmouth boys in the service. The letters cover a wide geographical area, and represent varied services. The boys are all friends, and all members of the Class of 1942, of which I had the privilege of being faculty advisor. We are very proud of all Dartmouth men in the service and I think these letters are representative of them.

LT. LLOYD R. BISHOP '42 USAAFis now flying in Italy. He enlisted in January 1941 in the Coast Artillery, and, thatspring transferred to the Air Corps. Hespent a year and a half in the Puget Soundarea and reached the rank of Sergeant. Herelinquished this rank to become an aircadet and, after training in Texas, received his wings at Waco in June, 1943. Heleft for overseas at Christmas time and isnow a pilot of a B 24 Liberator bomber.

You know I can remember back to the "good old days" when I considered candle light as slightly romantic and appealing, but right at present I'm getting awfully sick of it.

We've been buzzing around here at a pretty good clip lately, and, needless to say, I've had no trouble in putting in my required flying-time for each month. We've had a change of pilots on our crew—the original came down with an acute attack of "combatitis" after a few rough missions. I like this new boy very much, however, and I'm doing much more of the flying myself—which is very satisfactory.

Perhaps I can give you a slight conception of an average day for us. We get up, under heavy protest, when it is still very dark or moonlight, as the case may be, and shiver our way into all,the clothes we can reach. This painful process is followed by a quick hundred yard dash to the kitchen where I load up my mess gear with whatever concoction the mess sergeant dreams up— (on "red letter" days he makes hot cakes). Shortly after breakfast (usually just coffee for me) which we eat back in our billets, it's time for "briefing," so we congregate for that—at which time, in true pseudo-Hollywood style, we are told how, when and where. Then comes the mission "self—cold altitude flying for hours on end (it's warming up when it gets to —10° C.) followed by mounting tension as the target comes into sight. Suddenly, out of nowhere, come ugly, black puffs of smoke—they're all around you and creeping closer, until you want to scream at anybody or anything. Then comes that wonderful cry of "Bombs away!" over the interphone, and you let out your breath with a big "whoosh!"—realizing suddenly that you've been holding it for some time—and start to look around. Somebody's been hit—their engine's blazing. Another starts a slow, sickening spiral that sort of hiccoughs every now and then—faster and faster. Then is the time some gunner usually shouts, "Fighters, sir, at three o'clock and high!" over the interphone. You try to be calm and reassuring by the tone of your answer, but your damn heart starts to knock hell out of your ribs, and you sneak a quick glance away from the lead ship to see if he's right. He always is. The ships start to huddle together a little closer—the strong protecting the weak—and we all turn for home, but watching over our shoulders as the enemy fighters wheel like vultures over our trail for the chance at a luckless, limping straggler. The ride home is always short if nobody has been wounded, but if you've lost an engine it takes years, and there's a tight ball of naked, gnawing fear in your belly as you watch the sky for those "vultures."

Back on the field at long last, the very first thing is a cigarette—with long, deep, wonderful drags. Your hand shakes a good bit with the match, but the guy you're "lighting" just grins and grunts his thanks. Then we put away our gear and head for the coffee-and-doughnut line, where smiling, teasing Red Cross girls look like movie stars. You thought for a few minutes that you'd never see a girl's smile again.

A little later "chow-call" brings us running for a hot supper (our only real meal of the day) with banging mess kits and excited talk of, "Boy! Did you see ...." and, "What the hell was ... ." etc. After dinner and the inevitable cigarette (rationed-Camels very scarce) comes a good quiet evening in our rooms with a game of cards, a letter to write, and sometimes a letter to read. All in all, a full life and an interesting one. I like it. I'm feeling exceptionally fine and am content with my work.

LT. ROBERT C. WHITE '42USMCR,writes from the South Pacific. He was inthe Marshall Islands attack.

My first experience at War has been a very sobering one. Frankly, I've had my belly full for a quite a spell, though I'm afraid that the Marine Corps may have different ideas on that score.

We attacked the northern islands of Kwajalein Atoll in the Marshall Islands early in February, as you probably remember from the radio and newspapers. It was really a Navy show, and they put on a terrific bombardment. We swept in afterwards and slugged it out for the actual ground, and got it. The first time you realize what war is, is when you see a buddy killed, or a dead Marine. The Japs don't count. There are stacks of them all around, some days old by this time, and there's that inevitable and indescribably nauseous stench. They look inhuman, and might be just so much cordwood for all you care, except for the stink.

It's too bad we couldn't all have been in the same outfit. I often think about the possibilities of that, with regret that it isn't that way. My sole support vocally is a down-Mainer from Mass. State. I'm looking forward to at least a couple of months rest, and some letters to amuse me, so let's get hot. I've got some good new songs for our reunion, too.

Looking back on it, I reckon that the Dartmouth Outing Club has come into possession of quite a few more shelters on Kwajalein Atoll. We built a batch of them. Four of us built one long, rambling structure of poles and palm fronds called the "Lakanooki Apts." Later a few more tenants added their flats, and the whole affair opened out on a quaint patio, boasting a gigantic foxhole for the convenience and protection of the tenants. We even observed a "siesta hour" and reposed on our mats sipping small slugs of "medicinal" brandy, captured Jap Saki (not so good) and Jap Beer (very good. It's labeled in Jap and English for export.)

I haven't got much to show for the fracas except coral cuts on my legs. You don't feel much like souvenir hunting, and besides, the "Post Troops" that land afterward get most of the stuff of any value. There's not much left for scavenging Artillerymen.

PFC DAVID SILLS '4 2who prefers theranks to a commission, writes a fine letterfrom Colorado. He was in the Kiska attack.

Bob White will doubtless be bored when I (figuratively) "sit on my butt and tell tall stories of the Upanishads"; Harry Bond (presumably) will be bored when I make a few geologic comments about Kiska Island, Rat Island Group, Western Aleutians, and Alaska, from whence we have come recently. But Harry is in Italy, B. W. is in the Marshalls, Dave Haze is on some Pacific base, Buddy is in Europe (I guess), Jim Thompson is at I-know-not-where, and Sally is in Hanover—the luckiest by far of the lot, I would say. So this time my comments shall be all for one, and one for all, or something.

I can pass over my personal adventures quite rapidly. In June the Regiment went to Fort Ord, California, which is near the Monterey of R. L. Stevenson and the Carmel of Robinson Jeffers and Sady (Sady's being a rather remarkable bar). There we found ourselves getting amphibious training, and part of a huge task force bound for ?????—except we were given winter clothing and were instructed by training bulletins headed, "Lessons of Attu," and Kiska was being bombed daily. The two outstanding features of Fort Ord were a pier restaurant called "Pop Ernest's," where we would eat abalone steaks and drink wine almost nightly. And the San Diego cruise—our first taste of amphibious living. We had a few passes in San Diego (in steel helmets and leggins) and some wonderful swims in the Pacific and sun baths on the beach in the shade of the artificial palm trees that appeared in "Guadalcanal Diary"' and "Gung Ho" and who knows how many other Pacific war movies.

To continue with the Kiska story, only briefly (for it is a long and involved one), requiring, among other things: a. a long evening of wine and talk, b. the war being over before I can tell all, and c. the showing of my pictures. However, we sailed from the States on a Navy transport, and stopped in at Adak for a while to romp in the mud and listen to the bombers flying overhead to bomb Kiska each morning. We sailed away to conquer the dragons and landed on a questionable beach on the morning of August 15th. John Rand and I shared the same landing boat along with what seemed to be half the American Army. We had a little spiked tea before we landed, and bravely sang, "Beer Barrel Polka"—expecting the proverbial hell to break loose any minute. But it didn't, and we landed on a strangely quiet island, remarkable chiefly for the wonderful rainbow that circled it like a halo, and the steep hill that went up from our beach. Well, after a day or so of hellish foxhole life we discovered that the Japs had left, and for the next month we fought for survival and warmth. Gradually we emerged from the primitive, and even washed and trimmed our beards. For pastime we had fishing, wild flower picking, wandering through Jap positions, finding the inevitable souvenirs, and playing poker.

Then we moved across the island and spent our days more profitably but less pleasurably digging in for, and erecting, Pacific Huts, working on roads, and unloading ships. Then the great day came, November 17th, and we loaded on a ship for the trip to Seattle. This took 18 days because of storms, adverse winds, our 1918 Liberty ship, and our participation in a sea rescue: a 1943 Liberty ship broke in two, and our ship picked up survivors. From Seattle we went to Camp Carson, and then on furlough to such places as the Cafe Society in New York and the Statler Bar in Boston. And now we are back

LT. HAROLD L. BOND '42is in theslogging infantry, and this letter comesfrom the Italian front.

One more rainy day and mud per usual, but I am sitting by a warm stove listening to the rain on the tent roof and happy that I am off the front for a while. I am in a field hospital with a bug that the doc calls "true dysentery" in my system. This little creature did what German shells couldn't do, though they tried hard enough, and after forty days up front he got the best of me. So I have a chance to rest, get gloriously clean again, change my clothes, sleep and read. It is luxurious, and I am not unhappy in the midst of comfort. To sleep in a bed, to get clean clothes, to be able to wash once, twice, or three times a day, to shower, shave and get a haircut, to eat regular food regularly, and most of all to completely relax in every way is indeed a joy. Feeling comes back in fingers and feet—a man is almost civilized once more.

I hope the next time I go back up that Spring will be here. They say that Spring in Italy is beautiful, and I know it can be no worse than winter is. Fighting in these mountains in winter weather is hellish. The only way to dry your thoroughly soaked clothes (that couldn't be wetter if you swam a river in them) is by body heat, and it is a painful process of several days with snow, slush, mud and water covering the ground and filling your fighting hole. However, it is all behind now and like a bad dream. I don't think war will be so impossible when it gets warm. It is always hell, but when your are warm and dry it won't be as bad.

I feel old, Sally, after this last stay at the front, and tired like I have never been before. I haven't got the enthusiasm I used to have. Maybe it's just my illness. In any case it's a bad feeling at my age. I shouldn't be tired at the tender age of twenty-three when a man is just beginning to work on the creation of his dreams. Perhaps it is because I am afraid that things won't change, and that there will always be wars like this one—that as long as men are intolerant and inconsiderate and greedy that they will go on killing each other. At times it doesn't make any sense. I think I would feel differendy if I were killing Japs instead of Germans, but I don't know. I hate the Germans enough to kill them and feel satisfaction—not joy—when I get quite a few. However, if I didn't get him, he'd get me. It is as simple as that, and it doesn't matter how he or I feel about it. It is selfpreservation and that is all. There are no heroics to it at all. Most of us do our duty the best we can and try and live through this war in one piece. You never realize how much of your life is unlived, or not fully lived, until a machine gun cuts a tree in two a foot and a half away from your head. And even then you don't think of it until you get back and think of what might be the case if he had missed his aim, or that piece of shell that glanced off your helmet had gone through instead. I was never so unaware of my life as when it was in the greatest danger and it came nearest to being over. You just don't think along those lines in action—otherwise you couldn't take it, or couldn't do your job. It is when you get back that you start thinking again. At the front you push it all out of your mind as rubbish. There are usually so many bullets and so much shrapnel flying through the air you say, "if I'm going to get it I am, and there isn't a damn thing I can do about it"—and go ahead and do your job without taking any silly chances. Such is the game of war.

I hadn't intended to write all this stuff. But there is little else to write about. The rain continues to pour down and the mud gets deeper every hour. Men and mules slip and curse, but go on fighting just the same. We fought on a mountain about the size of Moosilauke, and I remember thinking at the time how I used to climb them for pleasure in the old days. I wonder if I will again. There are a million things I want to do when I come home—not the least of which is revisiting you and your fireplace where you once told me that the Army would disillusion me. You were wrong on that score, Sally. The Army has built up my tremendous faith in the average soldier—the War has disillusioned menot in little people, but in big ones that cause such things as this to happen. However, this must rest for a while and as I run dry let me urge you to write 'cause I sure enjoy mail.

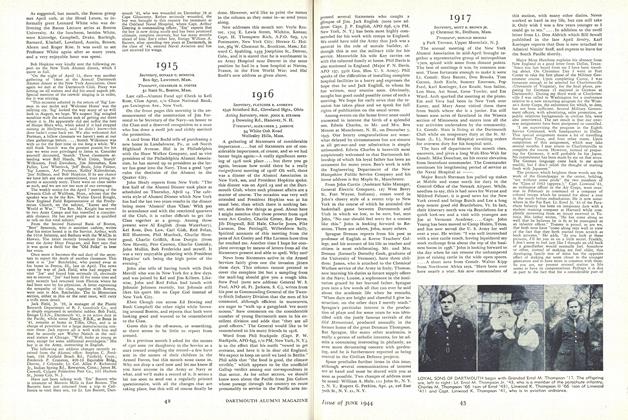

LT. LLOYD R. BISHOP '42, USAAF, Liberator bomber pilot, who writes from Italy.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Article

ArticleLaureled Sons of Dartmouth

June 1944 By H. F. W. -

Class Notes

Class Notes1943

June 1944 By EDWIN A. BOCK, WILLIAM T. MAECK -

Article

ArticleDARTMOUTH'S SKIPPER

June 1944 By HERBERT W. HILL -

Class Notes

Class Notes1917

June 1944 By MOTT D. BROWN JR., DONALD BROOKS -

Class Notes

Class Notes1918

June 1944 By ERNEST H. EARLEY, DONALD L. BARR -

Article

ArticleTHE NAUTICAL LIFE

June 1944 By PROF. RICHARD H. GODDARD '20

Lettter from the Editor

-

Lettter from the Editor

Lettter from the EditorEditorial Comment

FEBRUARY 1929 -

Lettter from the Editor

Lettter from the EditorEditorial Comment

JANUARY 1932 -

Lettter from the Editor

Lettter from the EditorWith Other Editors

FEBRUARY 1932 -

Lettter from the Editor

Lettter from the EditorThe Real World

JUNE/JULY 1984 By Douglas Greenwood -

Lettter from the Editor

Lettter from the EditorContinuing Education

APRIL • 1985 By Douglas Greenwood -

Lettter from the Editor

Lettter from the EditorA Family Affair

JANUARY/FEBRUARY 1986 By Douglas Greenwood