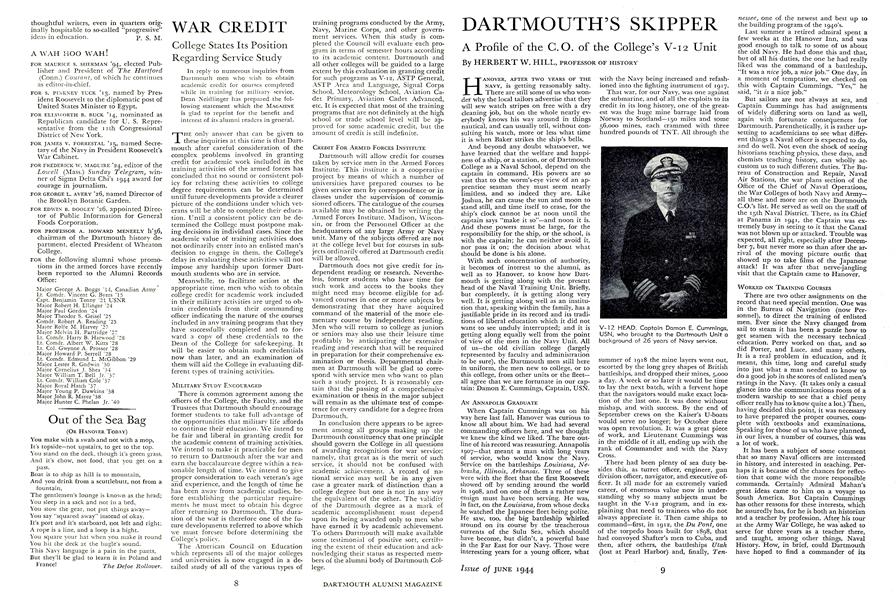

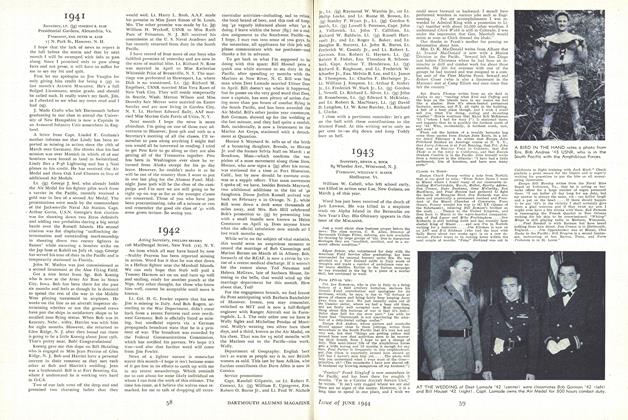

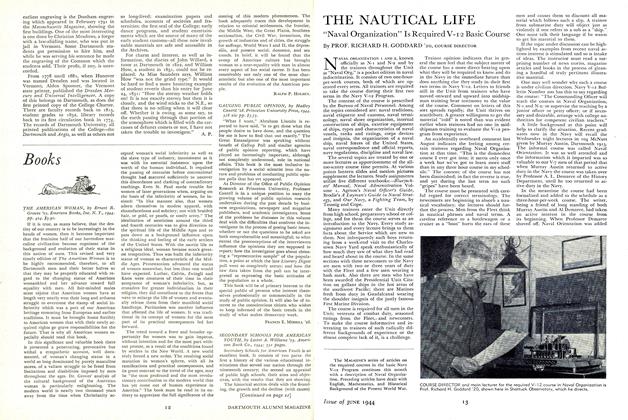

A Profile of the C.O. of the College's V-12 Unit

HANOVER, AFTER TWO YEARS OF THENAVY, is getting reasonably salty. There are still some of us who wonder why the local tailors advertise that they will sew watch stripes on free with a dry cleaning job, but on the whole nearly everybody knows his way around in things nautical, and can usually tell, without consulting his watch, more or less what time it is when Baker strikes the ship's bells.

And beyond any doubt whatsoever, we have learned that the welfare and happiness of a ship, or a station, or of Dartmouth College as a Naval School, depend on the captain in command. His powers are so vast that to the worm's-eye view of an apprentice seaman they must seem nearly limitless, and so indeed they are. Like Joshua, he can cause the sun and moon to stand still, and time itself to cease, for the ship's clock cannot be at noon until the captain says "make it so"—and noon it is. And these powers must be large, for the responsibility for the ship, or the school, is with the captain; he can neither avoid it, nor pass it on; the decision about what should be done is his alone.

With such concentration of authority, it becomes of interest to the alumni, as well as to Hanover, to know how Dartmouth is getting along with the present head of the Naval Training Unit. Briefly, but completely, it is getting along very well. It is getting along well as an institution that, speaking within the family, has a justifiable pride in its record and its traditions of liberal education which it did not want to see unduly interrupted; and it is getting along equally well from the point of view of the men in the Navy Unit. All of us—the old civilian college (largely represented by faculty and administration to be sure), the Dartmouth men still here in uniform, the men new to college, or to this college, from other units or the fleetall agree that we are fortunate in our captain: Damon E. Cummings, Captain, USN.

AN ANNAPOLIS GRADUATE

When Captain Cummings was on his way here last fall, Hanover was curious to know all about him. We had had several commanding officers here, and we thought we knew the kind we liked. The bare outline of his record was reassuring. Annapolis 1907—that meant a man with long years of service, who would "know the Navy. Service on the battleships Louisiana, Nebraska, Illinois, Arkansas. Three of these were with the fleet that the first Roosevelt showed off by sending around the world in 1908, and on one of them a rather new ensign must have been serving. He was, in fact, on the Louisiana, from whose decks he watched the Japanese fleet being polite. He saw, too, the big battleship whirled around on its course by the treacherous currents of the Sulu Sea, which should have become, but didn't, a powerful base in the Far East for our Navy. Those were interesting years for a young officer, what with the Navy being increased and refashioned into the fighting instrument of 1917.

That war, for our Navy, was one against the submarine, and of all the exploits to its credit in its long history, one of the greatest was the huge mine barrage laid from Norway to Scotland—150 miles and some 56,000 mines, each crammed with three hundred pounds of TNT. All through the summer of 1918 the mine layers went out, escorted by the long grey shapes of British battleships, and dropped their mines, 5,000 a day. A week or so later it would be time to lay the next batch, with a fervent hope that the navigators would make exact location of the last one. It was done without mishap, and with success. By the end of September crews on the Kaiser's U-boats would serve no longer; by October there was open revolution. It was a great piece of work, and Lieutenant Cummings was in the middle of it all, ending up with the rank of Commander and with the Navy Cross.

There had been plenty of sea duty besides this, as turret officer, engineer, gun division officer, navigator, and executive officer. It all made for an extremely varied career, of enormous value now in understanding why so many subjects must be taught in the V-12 program, and in explaining that need to trainees who do not always appreciate it. Then came ships to command—first, in 1912, the Du Pont, one of the torpedo boats built for 1898, that had convoyed Shafter's men to Cuba, and then, after others, the battleships Utah (lost at Pearl Harbor) and, finally, Tennessee, one of the newest and best up to the building program of the 1940's.

Last summer a retired admiral spent a few weeks at the Hanover Inn, and was good enough to talk to some of us about the old Navy. He had done this and that, but of all his duties, the one he had really liked was the command of a battleship. "It was a nice job, a nice job." One day, in a moment of temptation, we checked on this with Captain Cummings. "Yes," he said, "it is a nice job."

But sailors are not always at sea, and Captain Cummings has had assignments of widely differing sorts on land as well, again with fortunate consequences for Dartmouth. Parenthetically, it is rather upsetting to academicians to see what different things a Naval officer is expected to do, and do well. Not even the shock of seeing historians teaching physics, these days, and chemists teaching history, can wholly accustom us to such different duties. The Bureau of Construction and Repair, Naval Air Stations, the war plans section of the Office of the Chief of Naval Operations, the War Colleges of both Navy and Armyall these and more are on the Dartmouth C.O.'s list. He served as well on the staff of the 15th Naval District. There, as its Chief at Panama in 1941, the Captain was extremely busy in seeing to it that the Canal was not blown up or attacked. Trouble was expected, all right, especially after December 7, but never more so than after the arrival of the moving picture outfit that showed up to take films of the Japanese attack! It was after that nerve-jangling visit that the Captain came to Hanover.

WORKED ON TRAINING COURSES

There are two other assignments on the record that need special mention. One was in the Bureau of Navigation (now Personnel), to direct the training of enlisted men. Ever since the Navy changed from sail to steam it has been a puzzle how to get seamen with the necessary technical education. Perry worked on that, and so did Porter, and Luce, and many others. It is a real problem in education, and it meant, this time, long and careful study into just what a man needed to know to do a good job in the scores of enlisted men's ratings in the Navy. (It takes only a casual glance into the communications room of a modern warship to see that a chief petty officer really has to know quite a lot.) Then, having decided this point, it was necessary to have prepared the proper courses, complete with textbooks and examinations. Speaking for those of us who have planned, in our lives, a number of courses, this was a lot of work.

It has been a subject of some comment that so many Naval officers are interested in history, and interested in teaching. Perhaps it is because of the chances for reflection that come with the more responsible commands. Certainly Admiral Mahan's great ideas came to him on a voyage to South America. But Captain Cummings has other reasons for these interests, which he assuredly has, for he is both an historian and a teacher by profession. After his tour at the Army War College, he was asked to serve for three years as a teacher there, and taught, among other things, Naval History. How, in brief, could Dartmouth have hoped to find a commander of its Naval Unit who had a background more suitable for a program of educating men to be officers in the Navy?

But a paper record is not, after all, the whole story. Dartmouth men are much more interested in knowing how things are working out, and again it can be saidvery well. The most assiduous gatherers of local scuttlebutt have heard of no occasion when reasonable requests have been turned down or when suggestions for change have not received careful consideration. We are used, by now, to a quiet voice asking if there is any way the Navy can help with College problems, and particularly with the big problem of relating education to Naval needs. Without ever a suggestion, it must be added at once, that the point of view of the liberal college be abandoned. We are also used to the same quiet voice asking if there is room for a visitor in the back of the classroom—and we are delighted that the Captain is interested enough to come and see what is going on. The men in the classes like it, and feel their Commanding Officer is really concerned about what they are doing. It isn't much, perhaps, but it shows something about the spirit of the Unit.

One thing more is worth telling. It is not easy running the largest V-12 Unit in the country, and the Captain puts in long days Yet for two hours on each of six Tuesday evenings he met with some half-dozen novice teachers of Naval History and explained to them how the Navy worked, and some of the problems it had: to face. And it was done with so much readiness, and enthusiasm, and, it seemed, delight, that it is no wonder to that group that Dartmouth has, so it thinks, the greatest possible chance of having not only the largest, but the best, V-12 Unit in the nation.

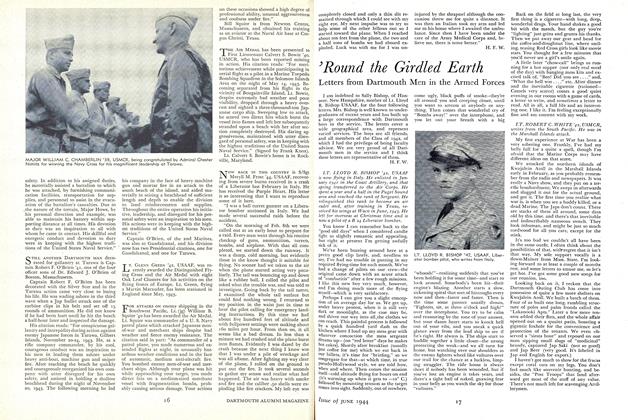

V-12 HEAD. Captain Damon E. Cummings, USN, who brought to the Dartmouth Unit a background of 26 years of Navy service.

PROFESSOR OF HISTORY

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Lettter from the Editor

Lettter from the EditorRound the Girdled Earth

June 1944 -

Article

ArticleLaureled Sons of Dartmouth

June 1944 By H. F. W. -

Class Notes

Class Notes1943

June 1944 By EDWIN A. BOCK, WILLIAM T. MAECK -

Class Notes

Class Notes1917

June 1944 By MOTT D. BROWN JR., DONALD BROOKS -

Class Notes

Class Notes1918

June 1944 By ERNEST H. EARLEY, DONALD L. BARR -

Article

ArticleTHE NAUTICAL LIFE

June 1944 By PROF. RICHARD H. GODDARD '20

HERBERT W. HILL

-

Article

ArticleTHE U. N. RECORD

April 1954 By HERBERT W. HILL -

Feature

FeatureThe 1955 Hanover Holiday Program

April 1955 By HERBERT W. HILL -

Article

ArticleComing: Hanover Holiday 1956

April 1956 By HERBERT W. HILL -

Books

BooksMITRE AND SCEPTRE.

MARCH 1963 By HERBERT W. HILL -

Books

BooksYESTERDAY'S RULERS: THE MAKING OF THE BRITISH COLONIAL SERV ICE.

OCTOBER 1963 By HERBERT W. HILL -

Books

BooksTRAVELS IN NORTH AMERICA IN THE YEARS 1780, 1781, and 1782.

MARCH 1964 By HERBERT W. HILL