The Opening Year

New Year's, for the colleges, comes with the opening of the fall term, in late September or early October as the case may be. It is the time of inaugurating another year's work, with a wholly new class just starting on its career.

As usual, it is a time of reassessment in our own case, with about the usual things to say of the situation. The incoming freshman class is forced to a somewhat smaller size this year, because the space is limited and because the numbers dropped from the upper classes have been so much fewer than in the recent past as to leave less room for taking in freshmen. That is to say, we are pretty close now to the normal condition in which each class must number about 500 men out of a total of 2000, instead of tapering gradually from about 600 freshmen to about 300 seniors.

This we believe should be welcomed as one of the most encouraging of indications, mainly because it reveals a distinct benefit ensuing from the present system of selecting candidates for admission. That the men admitted as freshmen are proving so much more generally capable of remaining in college throughout the course is exactly what one hoped to find to be true. Naturally the back-pressure reduces the volume of the incoming classes, and the tendency is to make 500 a sort of canonical expectation, so long as Dartmouth adheres to her determination not to encourage expansion beyond the 2000 total.

During the summer a great advance has been made in the building of the new Baker library. The process naturally militates for the moment against Hanover's traditional beauty, because there remains much to and tearing down as well as much building up—which must inevitably produce a transitory chaos. The comfortable certitude is that when the new emerges from the remnants of the old the appearance of our campus is going to surpass the most glowing dreams which the seers ventured to formulate in Dr. Tucker's pioneering day. The quadrangle at the northerly end of the ancient common should become notable for all time; and although one accustomed to the familiar row of ancient houses that used to line the street east of the white church will miss them hereafter, there is satisfaction in knowing that something infinitely finer and more useful has come to take their place. Butterfield, the first of the new buildings marking the advent of the New Dartmouth, has had to yield to the march of progress after 30 years or so of service—but that in turn will speedily give place to a habitation even better adapted to the present needs of the scientific departments which were housed therein.

This is not the place in which to detail all the architectural and other changes which those who come to the next Commencement will find to marvel at. One merely speaks of the more obvious instances in which the old order changeth, yielding place to new—and better. Dartmouth, having grown to her present size in point of students and faculty, must now provide facilities reasonably adequate to their accommodation. This she is doing, but it would be a serious mistake to suppose that everything needful is already either completed or well under way. It will be remembered that the Alumni Council, in response to a request from the Trustees, made a recent survey in which was published a statement of the numerous activities which it is either imperative, or highly desirable, to undertake before the physical plant can be deemed properly suited to the work it has to do. This Magazine has further pointed out the tremendous element of advantage which is involved in the fact that President Hopkins should have, in the normal course of nature, many more years of active life to devote to the development which benefactors of the instition may enable. What is now on the way to accomplishment is but the earnest of what is yet to come. The result will be a monument, not only to those who have had the most intimate part in its later building, but also to that long succession of noble and far-seeing men to whom we owe the foundations beneath it all.

The Fund in 1927

The completed report of the Alumni Fund committee for 1927 reveals the fact that for the first time in four years the subscription fell short of the assigned quota. Despite this failure to come fully up to the mark which had been set for the campaign, it should be noted that the gross amount of money actually raised was over $7OO beyond the sum realized the year before; that 224 more alumni contributed than in 1926; and that, while the gross sum contributed is a little more than $3500 short of the hoped-for $115,000, it at least suffices to wipe out the deficit for the year, enables the addition of $7036 to the principal of special class funds, $579 to the principal of the general fund, and allows $lOOO to cover the Tucker fellowship fund.

The quota set, $115,000, might still have been reached had there come to hand a single large individual contribution which had figured in other years, but which circumstances required this year to be omitted. As it is, the total secured (together with accrued income) was over $lll,OOO, collected at an overhead cost of only a trifle over 6 per cent., from rather more than 73 per cent, of the living alumni of the college—a most creditable showing. It represents the interest on considerably mare than $2,000,000 of endowment.

Once again, therefore, the College has been enabled by the open-handed and warm-hearted generosity of its graduates and non-graduates to close its books for the year without any item in red ink; and to Chairman Morris and his army of coadjutors in this arduous task is owing a hearty vote of thanks and appreciation for unremitting and highly successful toil. It remains to face the task of yet another year, strong in the confidence that the alumni spirit will be fully equal to the task of equalling, and hopefully of improving upon, the record made in 1927. The solicitation of so many thousand scattered alumni and non-graduate mem- bers of our enthusiastic fellowship is a prodigious work; and to marshal nearly three-quarters of the total number thereof as givers to the fund is an achievement which we believe is not even remotely approached by any other similar organization in any other American college.

Is It Worth While?

Repercussions of the questions raised by recent critics of American colleges continue to be found—among them surveys undertaken by curious folk among the undergraduates, east and west, with a view to discovering their ideas of what college education is all about and of how much it is seeming to them to be worth. Naturally the answers vary from the deeply pessimistic to the extremes of optimism. One is not surprised to find a few who affect the attitude of self-abasement, confessing that they feel they are wasting their own time and their parents' money, in quest of a degree which may not have much meaning for them after it is won. By some this appears to be regarded as evidence of a superior intellectual discernment, although it might be quite as plausibly regarded as no more than proof that the commentator in question really is out of place and should give ground to someone of less hopeless outlook. At least one, whose views are quoted, states that he feels the A. B. degree is merely useful as conferring the right to go farther and seek the A. M. and Ph. D. degrees—which latter apparently are regarded as having some gen uine merit of their own. Others aver their conviction that time spent in seeking the humbler academic distinction is not wasted at all, but is hardly to be measured by dollars and cents. And perhaps the best answer of any is that which would boil itself down to the convenient formula, "It all depends."

Every year, and especially at this season of new beginnings in the various colleges, there is heard a reminder that it would be well to remove the dead wood from the field and confine the work of the year to young men and women who have a real purpose for being in college and who offer some ground for believing that they will not wholly waste their opportunities while there. While this is a consummation devoutly to be wished, it is one which will never be more than approximated. in fact. We suspect it is folly to shed many idle tears over this, and folly also to devote too much effort to making surveys of the field, because the questions involved are, in several senses of the word, "academic." It is fairly certain that through many years to come there will be manifested an almost universal desire on the part of young people to go to college if they can, and on the part or parents and guardians to send them. It is further probable that there will be no lack of zeal on the side of such elders as themselves enjoyed this privilege in their own youth to see that their offspring have it too—despite the effort of occasional pessimists to reveal their low estimate of their own personal benefits therefrom.

Of course it necessitates smatterings and a sort of veneer, and this not unnaturally irritates those who would rather educate a chosen few very thoroughly than a multitude very imperfectly; but there is room for the belief that in the current situation of the people of the United States it does no harm, but rather much good, to go on very much as we are going. The most one may reasonably ask is that the raw material received thus at wholesale shall be straight-grained and sound, capable of being rounded into a wholesome citizenship for an intelligent, though not erudite, country, even though instances in which an exceptional scholarship is possible be but few and far between.

There is a steady increment of leisure time among us, remember, as industrial developments curtail the time required for the satisfaction of the world's material wants. It is well to strive for a widespread knowledge of how best to use that leisure, and how best to live in harmony and usefulness with one's fellows. That, perhaps, is the great function which a college serves in a country where the students are so appallingly numerous as they now are with us Americans.

The Late Professor Worthen

The death of Thomas Wilson Dorr Worthen, which came suddenly in the latter days of September, removes a man personally known and long held in the highest esteem by two generations of Dartmouth men. Identified as he had been since 1874 with the faculty of the college as a teacher of mathematics, Professor Worthen came into contact with almost every student in the days when mathematics formed a major requirement —a contact far more comprehensive than that of the teachers in many another department—and thus became a thoroughly familiar figure.

In addition he served for a considerable proportion of the time as an instructor in gymnastics, in the days before winter sport became the order of the day, during which an anxious faculty felt that some form of bodily exercise must be devised in order to keep sedentary students in reasonable winter condition. Later classes never knew that side of "Tute" Worthen—to give him the nickname by which he was universally, and one may add affectionately, known—and that is a pity, because in his avocation as an athletic instructor this mathematician gave demonstrations of his bodily vigor which were little short of marvellous. It was among Professor Worthen's accomplishments to seize two iron staples fastened into the wall of the old gymnasium in Bissell Hall and by the main strength of his two powerful arms hold his body and legs out rigidly horizontal above the floor—a feat far beyond the prowess of most students, even when fairly athletic. Just how long he could maintain that difficult posture, and at just what age he ceased to be capable of it, is not clear; but surely there are many among us who have seen him do it when he must have been nearly SO. He died at 82, but no one would have imagined that to be his age from anything in his appearance or from any slowing up of his activity. One always expected to see that alert, wiry man tripping energetically along the Hanover streets—as briskly in 1927 as in 1874.

It has been stated that at the time of his death Professor Worthen had served Dartmouth for more years than any other man then living. Graduating in 1872, he had come back to Hanover as a tutor in Greek and mathematics in 1874; and while he had given up active classes according to the retirement schedule some ten or a dozen years ago, he was still professor emeritus, and still a frequent visitor in Hanover, even after official duties connected with the State of New Hampshire led him to make his residence in Concord. To Dartmouth men he was always "Tute"—a reminiscence of his first teaching days—and by one and all he was sincerely beloved. He had been especially adopted into the honorary fellowship of the Class of 1891, but was equally honored and esteemed by every other class as well. Incisive, efficient, just, good humored, "Tute" Worthen has left behind him a memory in all our hearts which will never fade. He never courted popularity, but'popularity was his in fullest measure; and no other Dartmouth teacher, past or future, could be more sincerely mourned than he.

An Idea Taking Root

The deliberations reported early in the recent summer from a meeting of the institute for officers of administration of the higher institutions of learning seem to point toward a feeling very similar to that which some, years ago led Dartmouth College to devise and apply the selective process for determining admissions. It was the consensus at this summer gathering that there was urgent need for some method designed to eliminate from among the 850,000 or so of students in American colleges those matriculants whose seriousness of purpose is manifestly questionable, to say the least of it. The problem is to reduce, by forestalling their entrance, the number of those usually described as "wasters," or "loafers," whose attendance at the colleges is primarily a matter of idle pleasure; and the problem appeared to the above mentioned institute so important that it was spoken of as a problem on the satisfactory solution; of which depended the whole future of higher education in the country—whether it should continue to serve, or should break down.

Now Washington is a long way from Hanover, so that it is not altogether surprising to find the editors of the Washingon Post soliloquizing in this rather tvopless tone:

''When it comes to applying the test, however, the difficulty of the problem becomes apparent. How best can the American college and university go about limiting its enrollment by confining it only to serious students? Surely, not by today's intelligence tests, which have been tried and found wanting. Surely, not by more severe admission examinations or by more strict preparatory school standards, as a substitute for which the intelligence tests originally were offered. So far, science has not been able to grade satisfactorily the combination of preparation, ability, seriousmindedness, power of application and the other attributes so desirable in the ideal college student. This constitutes the problem of the age for the American college and university, for until a method is devised by which college admissions can be intelligently limited it is folly to anticipate any improvement over present conditions.''

Very possibly the Post would feel less acutely apprehensive if it studied for a brief space the selective process as used at Dartmouth, in connection with the recent developments in Dartmouth statistics indicative of a very creditable amount of success in attaining the objects referred to in the editorial Jeremiad above quoted. Reference has been made in these columns before to the evidence afforded by the past year's record, in which the "mortality" among the four classes due to deficiences in scholarship revealed a pronounced, and indeed an unexpected, recession from the distressingly high figures of some previous years. When it is shown that this is a regular thing, rather than a sporadic phenomenon, it will be perhaps safer to start the cheering; but the indications at present are that the system pioneered by Dartmouth really will work pretty well, if conscientiously served by both the college authorities and the alumni in co operation with them. It would be well to bring the Dartmouth instance to the attention of the editors of the Washington Post as a harbinger of hope that the problem is not so nearly insoluble as the pessimistic tone of its editorial comment might imply.

Who Shall Steer?

It may be a conclusion forced by the prejudices of crabbed age, but on reading the undergraduate suggestions with respect to reforms in the College curriculum as lately heralded in the press, many an alumnus is fairly certain to feel that we have had about all the undergraduate enlightenment that is good for us, so that it may be time to abandon the quest for information and let the college affairs be guided by the officers of instruction. The most recent survey conducted by the students suggests a great variety of amendments, ranging from the manner in which courses should be conducted and examinations given, all the way to a highly exotic flower in the groves of Academe to be denominated a "vagabond course," under which a student not a candidate for any degree should have free access to all the college facilities to use as he may see fit. As between the ultra-perfections demanded by the student body, and the imperfections alleged to inhere in the older fashion of direction by the president and faculty, one may be tempted to prefer the latter. It may be very nearly time to enunciate the principle that the College should be run by those whose professional business it is to run it, and that any who find the regime intolerable be given leave to withdraw to some more agreeable clime. To a certain extent we are ready to sit at the feet of the youthful Gamaliels; but there are limits and there is a pardonable suspicion that they have been reached.

Particularly inconsistent appears to be the demand that admission to Phi Beta Kappa be based, not on the work of an entire college course, but upon specially conducted examinations. If that idea is valid, our present theories at Dartmouth as embodied in the Selective Process are manifestly wrong. We cannot agree to that for a moment. We certainly cannot treat examinations as unsatisfactory criteria for admission to college, and then say that they are the only satisfactory tests for membership in Phi Beta Kappa. Further, we suspect that if the examination system were now in vogue, a clamor would be heard for changing to the system actually now employed—and with infinitely better sense.

Taken by and large, we cannot find in the most recent exhibit of undergraduate theories as to the proper running of a college very much reason to believe that merit is to be acquired in that way.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Article

ArticleTODAY'S RESPONSIBILITY OF THE AMERICAN COLLEGE

November 1927 By President Ernest M. Hopkins -

Article

ArticleDICK'S HOUSE

November 1927 By Eugene Francis Clark '01 -

Class Notes

Class NotesCLASS OF 1899

November 1927 By Louis P. Benezet -

Article

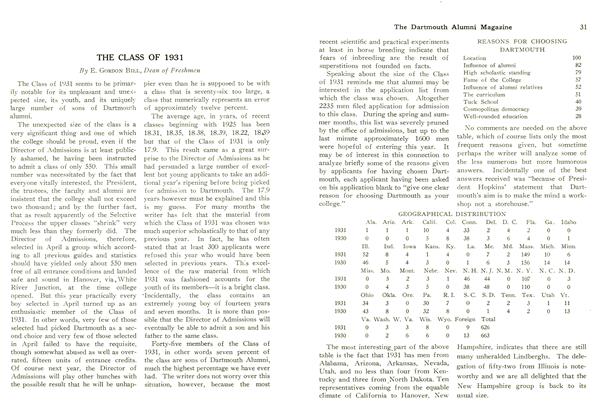

ArticleTHE CLASS OF 1931

November 1927 By E. Gordon Bill -

Class Notes

Class NotesCLASS OF 1911

November 1927 By Prof. Nathaniel G. Burleigh -

Class Notes

Class NotesCLASS OF 1921

November 1927 By Herrick Brown

Lettter from the Editor

-

Lettter from the Editor

Lettter from the EditorBolte Letters

February 1943 -

Lettter from the Editor

Lettter from the Editor'Round the Girdled Earth

May 1943 -

Lettter from the Editor

Lettter from the Editor'Round the Girdled Earth

August 1943 -

Lettter from the Editor

Lettter from the EditorRound the Girdled Earth

June 1944 -

Lettter from the Editor

Lettter from the EditorLetters from Dartmouth Men in the Armed Forces

April 1944 By H. F. W. -

Lettter from the Editor

Lettter from the Editor'Round the Giridled Earth

August 1944 By H. F. W.