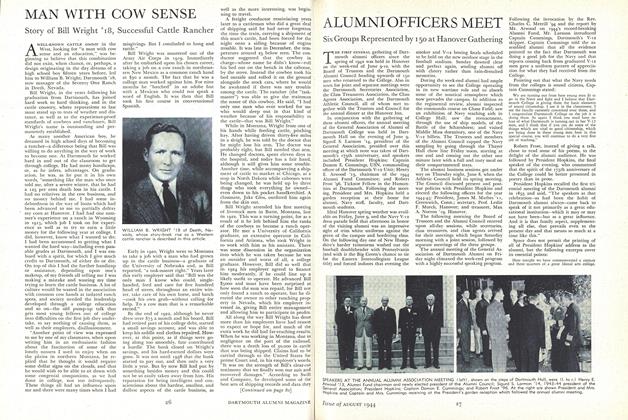

Story of Bill Wright '18, Successful Cattle Rancher

A WELL-KNOWN CATTLE owner in the West, looking for "a man with cow . sense and an education," was beginning to believe that this combination did not exist, when chance, or, perhaps, a design originating in the day dreams of a high school boy fifteen years before, led him to William B. Wright, Dartmouth '18, now manager of the Seventy One Ranch in Deeth, Nevada.

Bill Wright, in the years following his graduation from Dartmouth, has joined hard work to hard thinking, and in the cattle country, where reputations to last must stand up to tests of weather and distance, as well as to the experience-proof standards of cowboys and ranchmen, Bill Wright's name is outstanding and permanently established.

As many another American boy, he dreamed in high school days of becoming a rancher—a difference being that Bill was willing to do anything in the way of work to become one. At Dartmouth he worked hard in and out of the classroom to get through college. He had many handicaps, or, as he infers, advantages. On graduation, he was, as he put it in his own words, "something like the man who once told me, after a severe winter, that he had a 125 per cent death loss in his cattle. I had no relatives in the cow business, and no money behind me. I had some indebtedness in the way of loans which had been advanced to me to partially defray my costs at Hanover. I had had one summer's experience on a ranch in Wyoming in 1915, which job I took on for experience as well as to try to earn a little money for the following year at college. I did, however, know what I wanted to do; I had been accustomed to getting what I wanted the hard way—including even passable grades at Dartmouth, arid I was embued with a spirit, for which I give much credit to Dartmouth, of either do or die. On top of this I had the further handicap or assistance, depending upon one's makeup, of my friends all telling me I was making a mistake and wasting my time trying to learn the cattle business. A lot of culture would be wasted in the association with common cow hands at isolated ranch spots, and society needed the leadership developed through a college education and so on—the old pump-up talk that gets most young fellows out of college into difficulties on the first job they undertake, to say nothing of causing them, as well as their employers, disillusionment.

"Another point of view was expressed to me by one of my classmates, when upon writing him in an enthusiastic fashion about the fascination of some of the lonely sunsets I used to enjoy when on the plains in northern Montana, he replied that he thought it would require some dollar signs on the clouds, and that he would wish to be able to sit down with some congenial companions, as we had done in college, not too infrequently. These things all had an influence upon me and there were many times when I had misgivings. But I concluded to hang and rattle."

Bill Wright was mustered out of the Army Air Corps in 1919. Immediately after he embarked upon his chosen career, taking a job on a cow ranch in northeastern New Mexico as a common ranch hand at $30 a month. The fact that he was a college man worked against him. For nine months he "batched" in an adobe hut with a Mexican who could not speak a word of English. It was then that Bill took his first course in conversational Spanish.

Early in 1920, Wright went to Montana to take a job with a man who had grown up in the cattle business—a graduate of the University of Nebraska and, as Bill reported, "a task-master right." Years later this early employer said that "Bill was the only man I know who could, single-handed, feed and care for five hundred head of steers, throughout an entire winter, take care of his own horse, and batch —cook his own grub—without calling for help. To a cow man that is a remarkable record."

By the end of 1922, although he never drew over $75 a month and his board, Bill had retired part of his college debt, started a small savings account, and was able to keep his saddle and clothes repaired. However, at this point, as if things were going along too smoothly, fate contributed a hurdle. The bank closed on Wright's savings, and his hard-earned dollars were gone. It was not until 1938 that the bank started to pay out, and then only a very little a year. But by now Bill had put by something besides money and this could not be so easily taken away from him. His reputation for being intelligent and conscientious about the hardest, smallest, and dullest aspects of the cattle business, as well as the more interesting, was beginning to travel.

A freight conductor reminiscing years later to a cattleman who did a great deal of shipping said he had never forgotten the time the train, carrying a shipment of this man's cattle, had been forced for the night onto a siding because of engine trouble. It was late in December, the temperature around 25 below zero. The conductor suggested that the cowboy in charge—whose name he didn't know—roll his bed out on the bench in the caboose, by the stove. Instead the cowboy took his bed outside and rolled it on the ground alongside the stock cars, where he would be awakened if there was any trouble among the cattle. The rancher (the "taskmaster") was able to give the trainman the name of this cowboy. He said, "I had only one man who ever worked for me who would sleep out in that kind of weather because of his responsibility to the cattle—that was Bill Wright."

While in Montana, Wright froze one of his hands while feeding cattle, pitching hay. After having driven thirty-five miles in a sleigh, he was told by the doctor that he might lose his arm. The doctor was probably right, but Bill needed that arm. He changed doctors, spent eleven days in the hospital, and today has a fair hand, although it still gives him some trouble. Another time, while accompanying a shipment of cattle to market at Chicago, at a stop in North Dakota while cabooses were being changed, he was held up by three thugs who took everything he ownedeven down to his pocket handkerchief. A classmate, Jake Glos, outfitted him again from the skin out.

Bill Wright attended his first meeting of livestock men in Butte, Montana, late in 1922. This was a turning point, for as a result of it he left behind him the ranks of the cowboys to become a ranch operator. He met a University of California graduate, an extensive operator in California and Arizona, who took Wright in to work with him as his assistant. There was some dissension in the organization into which he was taken because he was an outsider and worst of all, a college graduate. However, Bill did so well that in 1924 his employer agreed to finance him moderately, if he could line up a likely outfit to operate. He advanced Bill $5000 and must have been surprised at how soon the sum was repaid, for Bill not only found a ranch to operate, but he directed the owner to other ranching property in Nevada, which his employer invested in, giving Bill entire management and allowing him to participate in profits.

All along the way Bill Wright has done more than his employers have had reason to expect or hope for, and much of the extra work he did had far-reaching results. When he was working in Montana, due to negligence on the part of the railroad, there was a death loss of 30,000 in cattle that was being shipped. Claims had to be carried through to the United States Supreme Court and, in his employer's words, "It was on the strength of Bill's clear-cut testimony that we finally won our suit and recovered damages." According to Swift and Company, he developed some of the best sets of shipping records and data they had ever seen. He worked up figures of range cattle costs from the time steers were turned loose on open ranges until they were hung up on the hook in the packing house in Chicago. This set of figures was taken as a basis for the outstanding range cattle cost studies subsequently developed by the University of Wyoming. His education was no longer spoken of as a detriment.

Wright moved to Nevada in 1926; he has been there ever since. It would seem that one factor in his steady success has been that what he undertakes is so tough at the start that no other man wants to tackle it. Once Bill has licked the initial difficulties, he maintains his improvements and adds to them. The ranch that he took on in Nevada had been in the hands of a receivership for five years. It was badly run down and run over by trespassing sheep outfits and other neighbors who had encroached upon the private rights of the range. Bill was a newcomer in that part of the country, and getting this property into shape, legally as well as financially, was one of the hardest jobs he had attempted. There were fights in the courts; Bill had to carry a gun as a result of threats he received against his life; and he had generally to stand his ground. However, he achieved his purpose—which was to make his outfit what it now is: one of the most successful in the state, running between eight and ten thousand head of fine Hereford range cattle, an outfit which is well-balanced and commands the respect of neighbors and competitors.

In 1935 Wright organized the Nevada Cattle Growers' Association and was its president for seven years. In 1937 he began to serve on the Legislative Committee of the American National Live Stock Association and made a number of appearances before Congressional committees in Washington. At present he is chairman of the Legislative Committee and Vice President of the American National Live Stock Association.

It is not surprising that Bill Wright has been repeatedly urged to run for election to the United States Senate as the Repub-lican candidate from Nevada. However, especially at the present time, he feels that his job is producing beef, an essential war commodity.

He is the father of two boys. Their mother was a girl Bill had known most of his life. She taught both boys on the ranch, through primary school, and has had no small part in Bill's success. There can be no doubt that Bill Wright's career since Dartmouth is not only unique among his classmates but that in his modest and yet forceful perseverance, he has made his mark in the West against heavy odds, and that his continued success is the sincere wish of numerous friends.

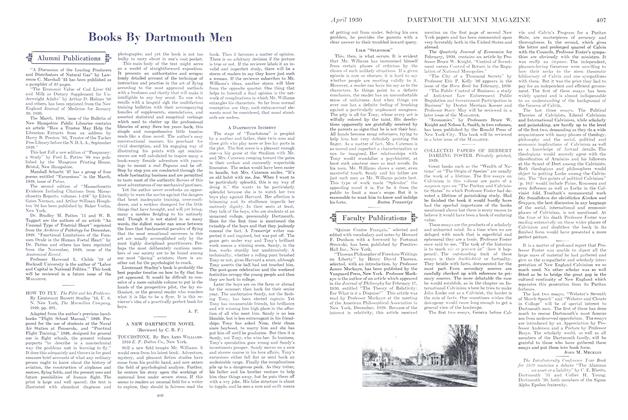

VELVET ROCKS IS A MISNOMER to the Dartmouth V-12 trainees who have to run the Commando Course winding 900 yards up and down the hill of that name east of Chase Field. Using natural obstacles and solid, hand-hewn timbers, Ross McKenney of the DOC directed its construction with student help. Among the 19 obstacles spaced 25 to 50 yards apart are the above (I. to r.) : Top—lo-foot ramp, rock ledge, and hand-over-hand ladder; Center—double tunnel and fence vault; Bottom—lo-foot scaling wall, the belly crawl, and the waterhole swing (for what happens to men not making this one see opposite page). The running time varies from six to fourteen minutes.

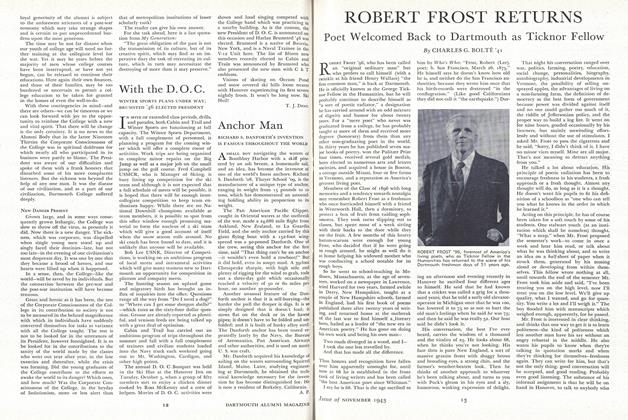

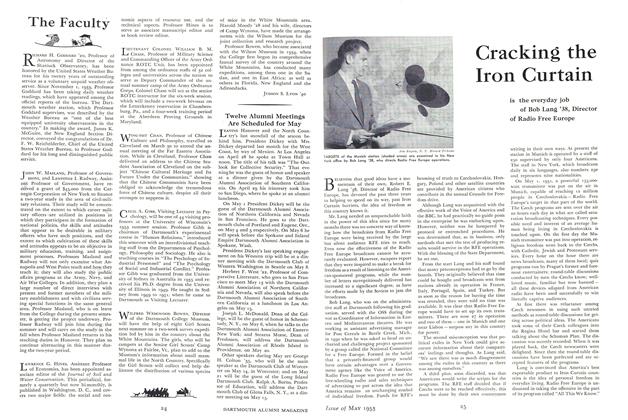

WILLIAM B. WRIGHT '18 of Deeth, Nevada, whose story-book rise as a Western cattle rancher is described in this article.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Article

ArticleA TEACHING LIBRARY

August 1944 By NORMAN K. ARNOLD -

Article

ArticleTHE HISTORIC COLLEGE

August 1944 -

Article

ArticleALUMNI OFFICERS MEET

August 1944 -

Article

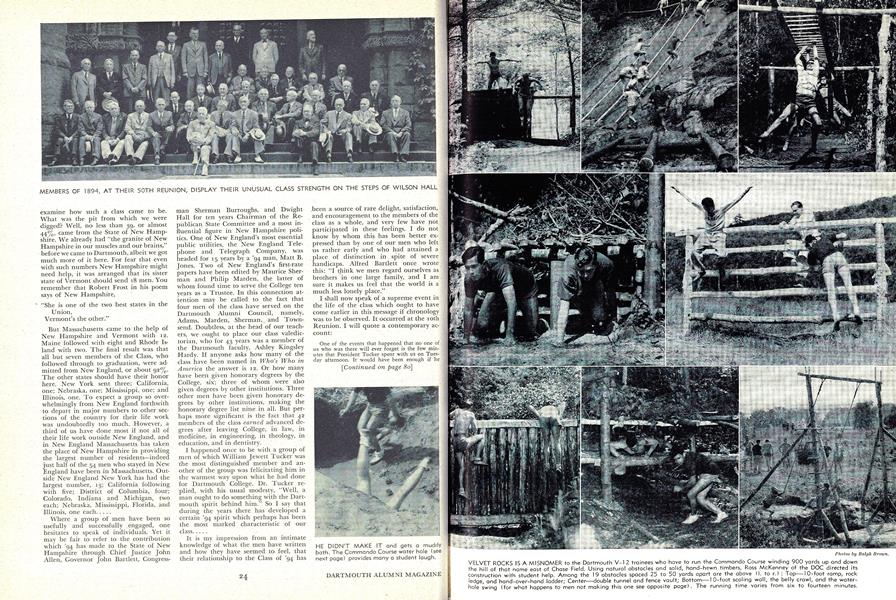

ArticleTHE 50-YEAR MESSAGE

August 1944 By REV. CHARLES C. MERRILL '94 -

Class Notes

Class Notes1904

August 1944 By DAVID S. AUSTIN II, THOMAS W. STREETER -

Lettter from the Editor

Lettter from the Editor'Round the Giridled Earth

August 1944 By H. F. W.

A. P.

Article

-

Article

ArticleASSOCIATED SCHOOLS HOLD COMMENCEMENT

June, 1914 -

Article

ArticleClimbing Mt. Olive

MARCH 1929 -

Article

ArticleClub President of the Year

NOVEMBER 1965 -

Article

ArticleImproving Potential

Jan/Feb 1981 -

Article

ArticleMichael Lempres '81 Chosen For White House Fellowship

SEPTEMBER 1988 -

Article

ArticleTHE UNDERGRADUATE'S RELATIONSHIP TO THE COLLEGE

November 1921 By ERNEST MARTIN HOPKINS