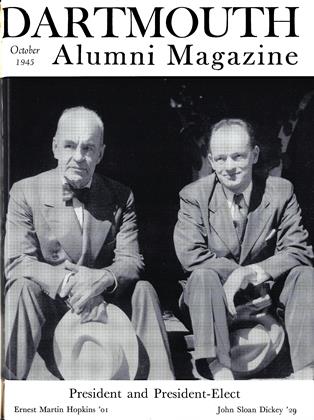

News of the retirement of President Ernest Martin Hopkins as head of Dartmouth College comes as no surprise now that the war is at an end. He had intended to resign upon reaching the age of 65, but the war intervened.

President Hopkins, with the longest service of any college head in New England, has had a notable career. President Tucker of Dartmouth, to whom "Hoppy" was secretary following his graduation from the Hanover institution, had launched Dartmouth upon its era of expansion. But it was Mr. Hopkins who had to finsh the job, by building an adequate physical plant and finding the ways and means of maintaining it, while at the same time preserving the integrity of Dartmouth as a liberal college and curbing tendencies ever recurrent to make the school a university.

Dartmouth has won a unique place in the world of higher education under Mr. Hopkins. It is more truly a national college than any other in this nation, despite its isolated location in one corner of the country. It has led the way in substituting annual alumni fund contributions for the degeneracy of endowment income common to all institutions under present economic and political conditions. It has remained free in a world in which" ideas have strangled both institutions and nations which clung too tenaciously to one or more of them, and so helps preserve the hope that the peoples of the world may work out their salvation in the end.

Dartmouth's very location has aided in all this, for man's perspective is better in the hills than when his vision is encompassed by the artificialities of metropolitan areas. But most of all it has been President Hopkins' own personality which has guided the college to an eminent-place in the whole field of higher education in this nation.

President Hopkins once spoke of "the aristocracy of brains," and brought down upon himself the derisive protests of the increasing multitude bent upon foisting upon humanity the pretension that all men are actually equal. He has at other times become engaged in controversy with lesser minds than his own, as at present with those who would distort the purposes and workings of Dartmouth's selective process of admissions, which he was instrumental in devising and inaugurating. But through it all, including internal and sometimes difficult disputes with the Dartmouth faculty, he has maintained an unperturbed demeanor of leadership.

He still leads in the moment of his retirement, for it is a reflection of his own concepts that Dartmouth turns to a young man as his successor, as he himself was young when he went to Hanover as President 29 years ago. We predict, too, that he will so manage his own affairs that he does not embarrass his successor, who must start his career at Hanover by readjusting Dartmouth to the peace, a task made easier because President Hopkins handled the adjustment to war so well.

We don't believe that "Hoppy" is much concerned about the measure of immortality which may be his. Yet he has left a mark which will not be erased for a long time, as humans think of time. He has advanced the knowledge of many thousands as to the art of living, which is the' objective of all education, or should be. He himself has lived magnify cently, with that tolerance which is born only of understanding and appreciation of other men. His reward has been an affection few this world ever win from their fellows.

But time marches on. President Hopkins who could have died in the office, steps aside voluntarily. He seeks only to assure to the institution from whose leadership he retires a continuation of the freedoms it is dedicated to help preserve. Dartmouth will be more able to remain great because of the foundations he has built.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Article

ArticleHARRY L. HILLMAN

October 1945 By SIDNEY C HAZELTON '09, -

Article

ArticleDARTMOUTH'S NEW LEADER

October 1945 -

Article

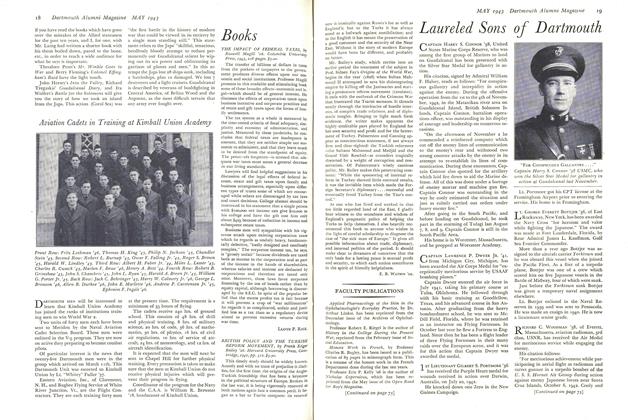

ArticleLaureled Sons of Dartmouth

October 1945 By H. F. W. -

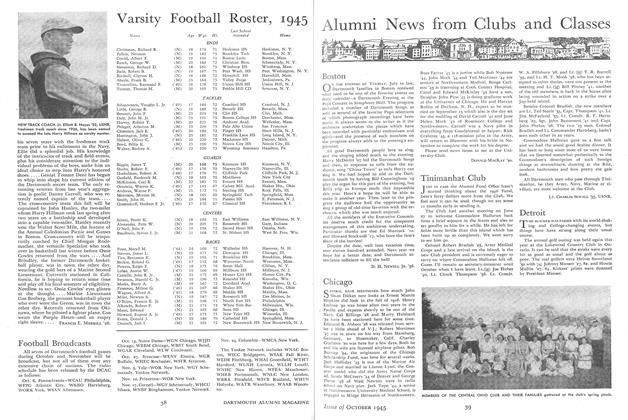

Class Notes

Class Notes1918

October 1945 By ERNEST H. EARLEY, DONALD L. BARR -

Class Notes

Class Notes1917

October 1945 By MOTT D. BROWN, DONALD BROOKS -

Sports

SportsTHE FOOTBALL OUTLOOK

October 1945 By Francis E Merrill '26

Article

-

Article

ArticleAviation Cadets in Training at Kimball Union Academy

May 1943 -

Article

ArticleThe Dean of Whodunits

FEBRUARY 1994 -

Article

ArticleVISITING VOICES

JAnuAry | FebruAry -

Article

ArticleVIEWS ON WAR ARE SERIOUS

April 1943 By George H. Tilton III '44 -

Article

ArticleThe Players

NOVEMBER 1931 By I D. A. Hill -

Article

ArticleFree Speech at Issue

NOVEMBER 1969 By ROBERT B. GRAHAM