The 12 university presidents who object to action now on a bill providing for a year of compulsory military service after the war and who are, perhaps, opposed to the principle of such a program, have been answered by 14 of their brethren, including the presidents of Yale, Dartmouth, M. I. T. and Amherst. These gentlemen warmly advocate immediate enactment of legislation by Congress, to become operative after the war.

The 12 declare that while a war is raging the people are not in the proper mood, for weighing the merits or demerits of a system which would reverse our traditional practice. President Marsh of Boston University emphatically reechoed this judgment in a local radio debate last Saturday. References were made in that discussion to the foisting of the eighteenth amendment on the nation while its thoughts were centered on war problems.

Messrs. Seymour, Hopkins, King, Compton, at als., on the contrary, declare in their letter to the White House that if we do not make up our minds now, when the calamitous results of unpreparedness are obvious, we may "forget it" after the war, as in 1919 and 1920 and indefinitely thereafter. J. W. Farley of Boston restated this opinion vigorously in reply to President Marsh.

The resemblance between enactment of a compulsory service law now and of the prohibition amendment and laws in the first World War is not very close. Prohibition was related only remotely to the war, and probably most of the absent citizens were not drys. Camp training is linked to the ordeals which our men are undergoing, and probably an overwhelming majority of them favor compulsory training. Whether they would prefer a postponement of the decision is not known, but if casual evidence from those who have returned is a criterion they would line up with the 14 rather than the 12 presidents. The servicemen's attitude is presumably reflected in the various popular polls, which show that a large majority of the men and women would welcome compulsory service.

The 26 presidents have spoken for themselves only, of course, not for their alumni and undergraduates and not for the governing boards and faculties. There are indications that, like the clergymen who have spoken, most of the teachers believe that Congress should temporize and possibly refuse to act later. They fear that militarism would result. They would rely for national safety on international cooperation. One of their main reasons is that Uncle Sam should not be allowed to control the lives of young men for a year and expose them to temptations from which they are free now. But is this the conviction of most college graduates and undergraduates, young and old, in and out of uniform, and of their families?

It is decidedly questionable whether there is such a sharp clash of opinion between Yale, Dartmouth, M. I. T. and Amherst alumni, on one hand, and those of Harvard, Brown, Cornell and Princeton on the other as between the two quartets o£ presidents. Nor is it clear yet that the clergymen who would defer action represent a majority of the devoted laymen of the churches. The chances are that if Presidents Conant, Wriston, Day and Dodds should query the alumni of Harvard, Brown, Cornell and Princeton, respectively, the responses would delight Messrs. Seymour, Hopkins, Compton and King.

In 1775 Eleazar Wheelock, who founded Dartmouth College for the Christianizing of the American Indians, reported on his Revolutionary standing, "I esteem my present connection with Canada to be the strongest bulwark under God this new country has." The vulnerable Connecticut Valley was raided only once by Indians during the war, and then by a small party.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Article

ArticleSCHOOL FOR CRAFTSMEN

March 1945 By C. E. W. -

Class Notes

Class Notes1929

March 1945 By F. WILLIAM ANDRES, T. TRUXTON BRITTAN JR. -

Article

ArticleLaureled Sons of Dartmouth

March 1945 -

Class Notes

Class Notes1918

March 1945 By ERNEST H. EARLEY, DONALD L. BARR -

Article

Article'Round the Girdled Earth

March 1945 By H. F. W. -

Class Notes

Class Notes1919

March 1945 By J. KENNETH HUNTINGTON, MAX A. NORTON

Boston Herald

Article

-

Article

ArticleINTERESTING FIGURES GIVEN OUT ON SCHOLARSHIP OF 1927 CLASS

November, 1924 -

Article

ArticleGeorgia Club Trophy

May 1929 -

Article

ArticleOn the February Calendar

February, 1931 -

Article

ArticleThorny Presence

JUNE 1982 -

Article

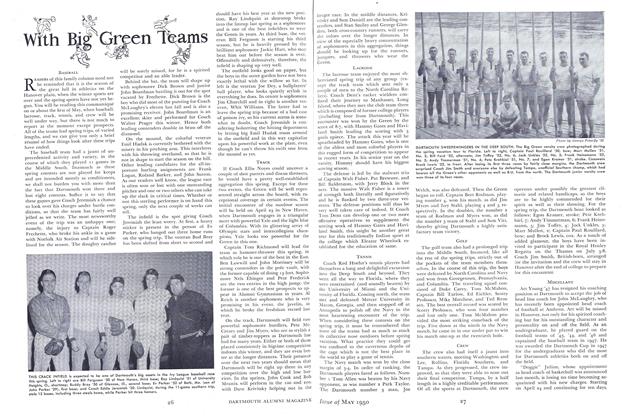

ArticleLACROSSE

May 1950 By Francis E. Merrill '26 -

Article

ArticleAlumni Affairs

January 1942 By The Edrror.