After President Kemeny's session with a hundred-odd applicants to the College during the recent spring break, I was introduced as an undergraduate who would be willing to answer any questions the high school seniors might have about Dartmouth.

One, the president of his school government, said that body had recently dissolved itself in favor of a a student-faculty group, and that he had expected his classmates would respond favorably to the move, but nobody had.

"No one really seemed to care. Do you sense a feeling like that at Dartmouth, a sort of ...

"Apathy?" I ventured.

Several years ago this magazine was filled with stories of the political activism on campus. Now it is highly doubtful that what was described could ever happen again. Why this is the case is not easy to explain.

"We had a sense of power then," said Gary Brooks, an assistant dean of the College and a member of the Class of 1970. "But all that we did had very little effect. Nixon was elected, social programs have been cut back ..." Brooks senses an air of resignation, of powerlessness, here and at other colleges. In the current "rush for professional schools he sees a turning inward.

"There's a very strong trend now toward self-gratification ... my gut feeling is that there is less social awareness and social consciousness. The McGovern campaign was the last gasp of the activist movement, and even the turnout for that was not that great."

"Apathy is not necessarily the right word," commented President Kemeny. On a one-to-one basis, I find students are just as concerned as they were three years ago.' Yet he agrees that we seem to be "more self-centered" and that there is a strong emphasis on self-examination" before we try to convince others of the righteousness of our cause.

They seem to be more and more unsure about what to do with their lives ... this is a very disturbing trend." The rush to law school? Simply a desire to avoid deciding what to do for a few more years.

Several factors have brought about this change in attitude, the President feels. Though he admitted it might be a cynical view, the end of the draft, he offered, might be one cause of the decline in student activism. The poor job situation makes for an increasing emphasis on studying harder and getting less involved in radical causes to please the professional schools. Finally, the results of all the work of a few years ago? Not very much, he said.

Cynical is history professor Jonathan Mirsky's word for it. Such examples as the ITT affair in Chile, the Watergate bugging incident, the cutting of funds for colleges and medical schools across the nation are enough to answer for him the question of why there is cynicism.

Students here are basically lazy, said Mirsky. They are pampered too much, not forced to do anything tough. "It's all handed to them," so when things don't work out, when all that effort in the 1960's accomplished very little, they give up.

"They're not even reading newspapers anymore; they get too depressed."

There are some, though, who are optimistic, if that is the right word.

"They are tired," Dean of the Tucker Foundation Charles Dey commented. "The context today is different too. The national mood has changed, we seem to be emotionally spent after the activism of the 1960's.

"But the emphasis, now is on getting the skills and training in order to get into a position where one can do something directly. People will not listen to someone these days unless he has the credentials," and this is what students are trying to do.

Dean of the College Carroll Brewster agreed. "The morale here is of a different order than at other colleges; it's high. And the public morality of our students is as deep as it's been since I went to college.

Students are planning their futures more carefully, he continued, and "there seems to be an almost universal devotion to public service.

"In 1969, the students oversimplified the issues and the ways they could deal with them." Taking over buildings sprang from a "notion that something could be accomplished in a war against universities that are really very frail things, a notion that reflected a unreal view of the world. There's no way that sort of thing could happen now."

So here are two varying sets of analyses — both, it should be noted, based on the same set of facts and focusing on the same body of people: they, or, as I have slipped in this piece occasionally, "us."

There is nothing happening here. Yes, we are studying more; yes, we are applying to graduate school in greater numbers; and yes, I think we are tired, very tired.

Many of us were in high school when the universities "erupted," and many of us turned out then to work for things we believed in, eager to help where we could and where we felt we were needed.

But, too, we have become cynical, which Professor Mirsky defined as "being skeptical that man's actions will have good results." The country as well has become cynical: all of us accept the corruption in government we know to be there. Who now is questioning why things are the way they are? No one, certainly, it seems; not the majority of the American people, in whom so many of us had so much faith just a few years ago.

Unfortunately, all I can do here is state the reality I see about me. I have to be honest and say that I don't feel I can accurately see the forest for the trees.

Nothing is happening though; the situation looks pretty bleak. And now it looks as if it's spreading to the high schools.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

FeatureWhat's So New About It?

May 1973 By Joanna Sternick, A.M. '72 -

Feature

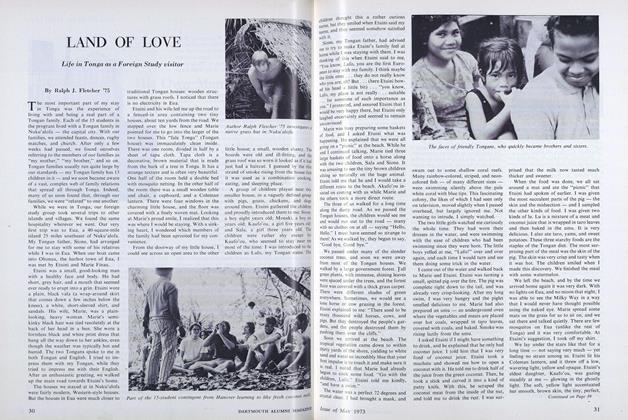

FeatureLAND OF LOVE

May 1973 By Ralph J. Fletcher '75 -

Feature

FeatureSCOPE: Off-Campus Options Made Easier

May 1973 By MARY ROSS -

Article

ArticleThe Indian Yell Revisited

May 1973 By Russell O. Ayers '29 -

Article

ArticleFaculty

May 1973 By ROBERT B. GRAHAM '40 -

Article

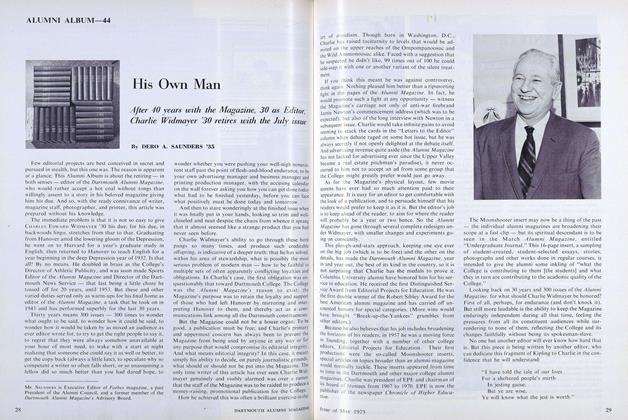

ArticleHis Own Man

May 1973 By DERO A. SAUNDERS '35

DREW NEWMAN '74

-

Article

ArticleThe Undergraduate Chair

APRIL 1973 By DREW NEWMAN '74 -

Article

ArticleThe Undergraduate Chair

JUNE 1973 By DREW NEWMAN '74 -

Article

ArticleThe Undergraduate Chair

October 1973 By DREW NEWMAN '74 -

Article

ArticleThe Undergraduate Chair

January 1974 By DREW NEWMAN '74 -

Article

ArticleThe Undergraduate Chair

April 1974 By DREW NEWMAN '74 -

Article

ArticleThe Undergraduate Chair

May 1974 By DREW NEWMAN '74