It is a Pity, but the fact seems to be that the apostles of the cultural creed in liberal education and the devotees of the socalled "practical" school too often tend to resort to polemics in proving their pet doctrines orthodox, instead of adopting the tolerant attitude that both elements are necessary to a balanced intellectual diet. Circumstances admittedly have contributed to inspire in each side a distrust of the other, not to say a suspicion on each side that the other would not be sorry to see its opponent obliterated completely. That, however, undoubtedly overstates the case, for surely no one would wish to combat an unbalanced diet for the mind by creating an equally regrettable unbalance at the other end of the arc. Neither school of thought is justified in regarding the other as an instrument of evil; but as Rudyard Kipling once pithily remarked,

"Yearly green is the strife between Jubal and Tubal Cain."

In current conditions, with the world reshaping itself after an unsettling experience, there is bound to be a reconsideration of these two elements in what we now call "liberal education" to the end that there shall be a more equitable distribution of the intellectual vitamins. To change the metaphor, it would seem to be in order to assess the respective elements, not with the idea that either alone should be the central pillar of the educational edifice, but that each should be assigned its appropriate part. The clock equipped with a pendulum would be of little use without its hands—and vice versa.

Who shall say that a science is incapable of being taught as a liberal art? Or that a scholar of science all compact is a more useful man than a scholar with some conception of classical literature as a seasoning for his educational meals? After all, what we are seeking is the well-rounded man, equipped not only to serve, but also to enjoy, the life of his time. Efficiency is not enough, alone and by itself. Man doth not live by bread alone; and though it be necessary that he be fitted to earn his bread, it is also desirable that he be fitted to enjoy to the full the life which bread supports.

It is no doubt impossible to attain the ideal of the man who knows something about everything and everything about something, but it isn't a bad mark to shoot at. It doesn't mean that a man should be a Jack-of-all-trades and master of none; neither that he should be a super-expert in someone chosen line, with no inkling of other things. There's the soul of man to consider, whether one chooses to regard it as immortal, or as important only while breath remains in the body and while reason holds her throne. In the last analysis, liberal education is less concerned with the body than the mind; and the predominant question is that of the food convenient for the latter's development. Still it isn't by any means a one-sided problem, despite a common tendency to treat it as if it were. What we are after is not only an efficient capacity to support life, but a sufficient capacity to enjoy the same. If only the search could be prosecuted without the partisanship of jealousy on behalf of this thing, or that!

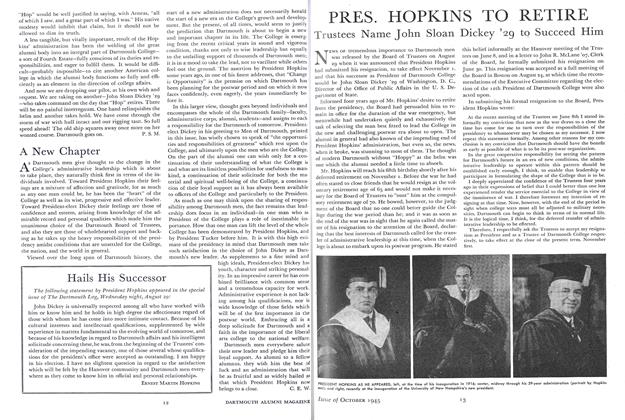

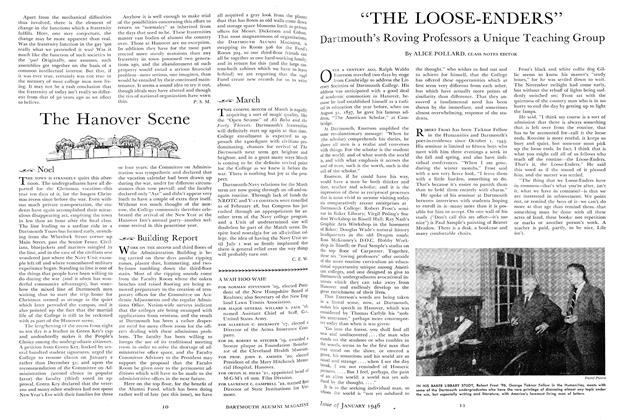

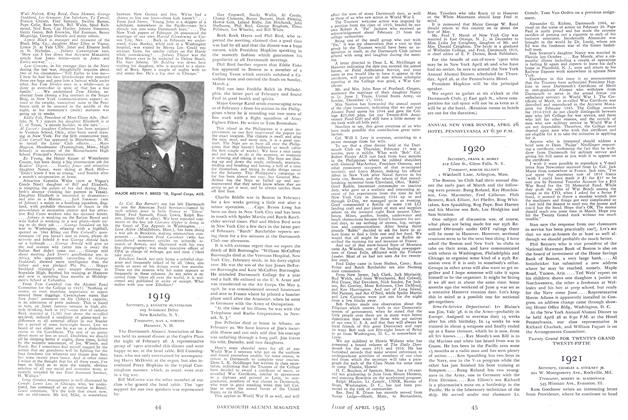

UNDER A MARCH SUN, NAVY TRAINEES LINE UP IN MASSACHUSETTS ROW'S SPRING FRESHETS.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Article

ArticleRADIO WAVES AND RADAR

April 1945 By GORDON FERRIE HULL JR. '33, -

Lettter from the Editor

Lettter from the Editor'Round the Girdled Earth

April 1945 By H. F. W. -

Article

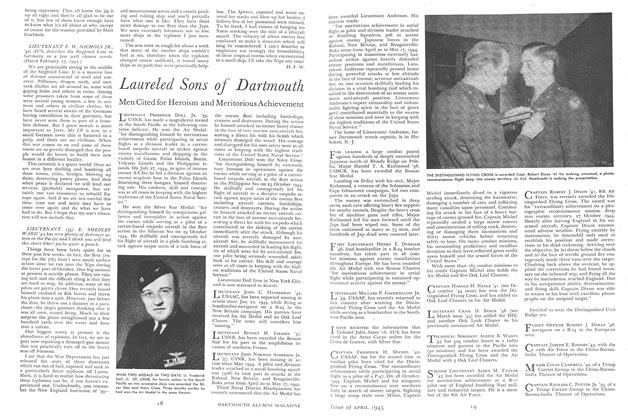

ArticleLaureled Sons of Dartmouth

April 1945 By H. F. W. -

Class Notes

Class Notes1918

April 1945 By ERNEST H. EARLEY, DONALD L. BARR -

Class Notes

Class Notes1945

April 1945 By ARTHUR NICHOLS -

Article

ArticleMedical School

April 1945