POSSIBLY THE EDUCATIONAL world is confusing itself unduly in its consideration of post-war curricula by exaggerating the alleged conflict between cultural and scientific aspects. At bottom, as we all know, the question does not involve making college education all "practical" or all "idealistic," but only the appropriate proportions of each to be provided for in a truly liberal education.

In that restricted view of it there is still abundant room for acrimonious debate; but at least one should start with the candid admission that the truly liberal education must make due account of what Emerson once summarized as . "law for thing" and "law for man." Study of the so-called "humanities" necessarily looks toward the past, where study of the sciences concerns itself with the future, and each has its pitfalls to avoid. Study of the humanities cannot afford to let itself become mere traditionalism; study of the sciences cannot afford to degenerate into mere experimentation or specialization. Somehow or other a balance must be struck between topics which make for material knowledge and topics which make 'for spiritual character. A ship equipped with the most efficient turbine engines, but without rudder or compass, would be a poor sort of ship; just as one with compass and rudder, but no motive power, would never get anywhere. Why not stop talking as if the one element or the other were of dominant, not to say exclusive, importance?

What liberal education seeks to produce is the well rounded man, equipped to make his way in the world and to enjoy life to the full. Granting that it would be folly to concentrate on worship of the past, it is still true that the past is an important guide to the contemplation of the future. Admitting that history and literature are in large part records of man's misconceptions and mistakes should not imply that therefore they must be ignored. The two elements, so far from being in conflict, are supplementary as adjuncts to the quest for truth. If "law for man" and "law for thing" are (in Emerson's phrase) unreconciled, the one relating to matter and the other to the spirit, at least they may be harmonized for man's greater glory.

Liberal education must be a combination of looking backward and looking forward, for the betterment of that ever-moving scintilla which is neither past nor future, but what we call the present. Roman mythology might have represented it as a Janus-faced affair,-viewing the known road by which we have come, and contemplating the unknown into which we must go, the better to inform our philosophy which as all Phi Betes know is the guide of life. Hence this protest against treating liberal education as something that must be all scientific, or all humanitarian, rather than as some figured flame that blends, transcends them all. May one suggest that extreme scientists and extreme humanists stop fighting—and get together?

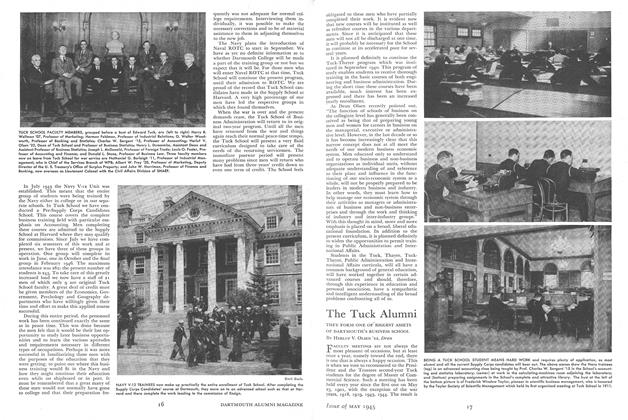

THE RISING SUN OF A SPRING DAY ACCENTUATES THE EXTENT AND CHARM OF THE CAMPUS.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Article

ArticleWHAT'S IN IT FOR US?

May 1945 By RICHARD E. LAUTERBACH '35 -

Lettter from the Editor

Lettter from the Editor'Round the Girdled Earth

May 1945 -

Article

ArticleLaureled Sons of Dartmouth

May 1945 By H. F. W. -

Class Notes

Class Notes1918

May 1945 By ERNEST H. EARLEY, DONALD L. BARR -

Class Notes

Class Notes1945

May 1945 By ARTHUR NICHOLS -

Article

ArticleAMOS TUCK SCHOOL

May 1945 By HARRYR. WELLMAN '07

Article

-

Article

ArticleDARTMOUTH ATHLETES IN THE WAR

January 1918 -

Article

ArticleSTEELE CHEMISTRY BUILDING

November 1921 -

Article

ArticleWORK ALREADY STARTED ON NEW DORMITORY

November, 1922 -

Article

ArticleNew Faculty Members

NOVEMBER 1929 -

Article

ArticleThe Senior Panel

June 1961 -

Article

ArticleRAY NASH AND GRAPHIC ARTS

February 1941 By Robert R. Rodgers '42.