COMPARATIVELY FEW, it is hoped, among civilized peoples Will oppose the general idea of world organization to insure future peace. There is evidence that opposition in this country, compared with the opposition of 1919 to the idea of the League of Nations, both in the United States Senate and among the citizens at large, is far less extensive and far less vocal than it was when President Wilson submitted his plan for the League. Our experience with that plan should be instructive, in that it clearly revealed the vulnerable spot. And as discussion is now proceeding it is also becoming clear that this Achilles' heel has not been immunized and probably will not be.

In theory, such plans usually involve the assumption that if 100 nations pledge themselves to abjure war as an instrument of national policy, and if one nation subsequently proves recalcitrant, the other 99 will promptly unite to penalize and fetter the one offender. In practice, the more probable result is that the projected unanimity among the 99 will be lacking and that (as a matter of comparative strength) the split will be more nearly 50-50. This is foreshadowed in the insistence of Stalin on the so-called "veto" power, whereby a nation, bent on what to others seems "aggression," may block united League action against itself and thus make it a matter of individual decision as to what shall be done.

Before criticizing this Russian attitude, it may be well to consider dispassionately if it be not a candid avowal of an attitude which other great and powerful nations would also take in the pinches involving their own interests. The whole success of such an organization rests in the end on the sincere readiness of all involved to live up to their promises in spirit and in truth. There would be little virtue in promising what one did not stand ready and willing to perform. All hands have got to say what they mean, and mean what they say; and what's more they must have what it is fashionable to call the guts to go through with it, instead of finding excuses for not doing so.

In fine, it will be wise if we are realistic in our estimate of what actually can be done in the present state of the world, rather than be idealistically enraptured by what it would be splendid to do, and what could be done if men in the mass were less imperfect. What we are after is insurance of world peace, to the extent that is now possible by international agreement among men as they are—and they are still a little lower than the angels to put it mildly. Nationalism is still a terribly potent force; and we may as well recognize that it is such, instead of pretending that it isn't there, or has been forever abjured by all peace-loving nations. Is there a nation on earth, with any pretense to civilization, that would not describe itself as "peaceloving?"

The real question is, how many of us are willing to surrender our sovereignty? It has to be done—done in spirit and in truth before we shall really get anywhere with international agreements to insure peace. Stalin isn't ready yet. Is anybody else? Until we are, it is to be feared we must keep ourselves in trim to make good against potential aggressors—ready, willing and obviously able to make good—and that is why there's so much to be said for compulsory military training.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Article

ArticleWHAT'S IN IT FOR US?

May 1945 By RICHARD E. LAUTERBACH '35 -

Lettter from the Editor

Lettter from the Editor'Round the Girdled Earth

May 1945 -

Article

ArticleLaureled Sons of Dartmouth

May 1945 By H. F. W. -

Class Notes

Class Notes1918

May 1945 By ERNEST H. EARLEY, DONALD L. BARR -

Class Notes

Class Notes1945

May 1945 By ARTHUR NICHOLS -

Article

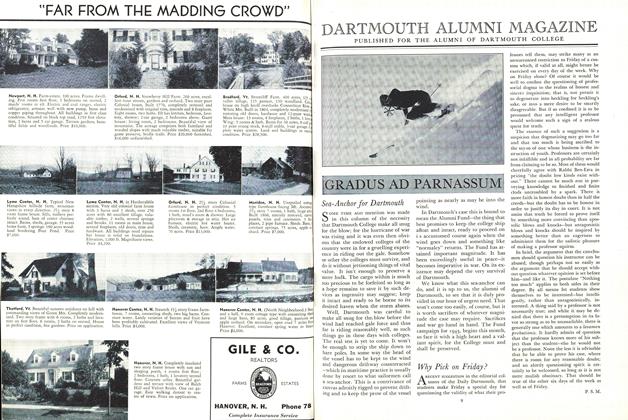

ArticleAMOS TUCK SCHOOL

May 1945 By HARRYR. WELLMAN '07

P. S. M.

-

Article

ArticleSea-Anchor for Dartmouth

January 1943 By P. S. M. -

Article

ArticleLooks a Fertile Field

February 1943 By P. S. M. -

Article

ArticleWhat Are the Liberal Arts?

November 1944 By P. S. M. -

Article

ArticlePost-War Planning

March 1945 By P. S. M. -

Article

ArticleLet Them Eat Spinach?

August 1945 By P. S. M. -

Article

ArticleA Lively Relic

January 1946 By P. S. M.

Article

-

Article

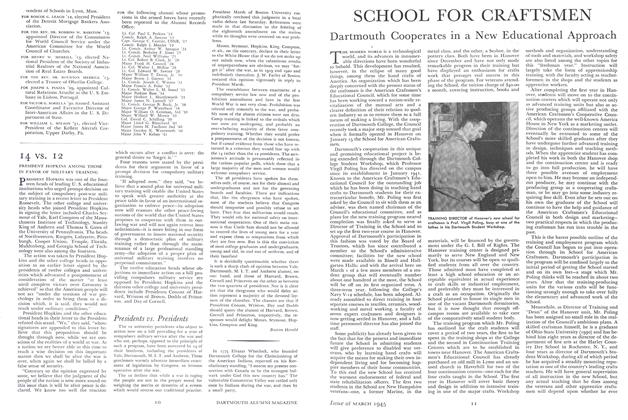

ArticleINFORMATION SERVICE ESTABLISHED IN PRESIDENT'S OFFICE

MARCH, 1928 -

Article

ArticleMorrill Memorial

October 1934 -

Article

ArticleA WAH-HOO-WAH!

December 1941 -

Article

ArticleDartmouth Awards Honorary Degrees to Six

July 1948 -

Article

ArticleMasthead

SEPTEMBER 1981 -

Article

ArticleONE STUDENT TYPE GONE

October 1943 By George H. Tilton III USNR