ByGeorge W. Elderkin '02. Princeton: Princeton University Store, 1958. 117 pp. $5.00.

In 1931 the Oxford University Press published a book by F. G. Gordon entitled Through Basque to Minoan. This was an attempt to solve the riddle of MinoanMycenaean writing via the almost equally mysterious language of the Basques. At that time neither Minoan-Mycenaean nor Basque was regarded as belonging to the IndoEuropean family of languages. In 1953, however, the late Michael Ventris offered a solution of one form of Minoan-Mycenaean writing (Linear B), from which he concluded that it was Greek of a type similar to that of the Homeric poems.

Professor Elderkin's book constitutes still another phase of the absorbing subject of the Greek language and its relations to other languages of the Indo-European group. It is a very difficult task, for, as he points out, no books in Basque were published until 1545. This fact makes it impossible to trace the changes in the language from the remote past down to that date.

The book is divided into two parts: 1. an introduction dealing with the geographical origins of the Basques and their migrations (Scythia, the Caucasus, Asia Minor, Egypt and North Africa, Spain, and finally Ireland); and 2. sixty-two pages of Basque words in alphabetical order, with suggestions as to their congeners in Greek and other Indo-European languages. There are also, in the first part, parallel lists of words illustrating the author's discussion of cognates in BasqueGermanic, Basque-Greek, and Basque-Irish. The book is bursting with erudition in the fields of legendary history, mythology, religion, and art.

The book is not, and, I feel sure, the author does not regard it as, a definitive study. Here are the disiecta membra, the raw materials which future scholars may utilize in continuing their work in this field. Herein lies the importance of the book. In the opinion of the present reviewer, however, the excitement of the chase has not infrequently led the author into making too imaginative and scarcely tenable suggestions. Mythical history is given too much authority in the attempt to reconstruct factual history. Throughout the book mythological and linguistic parallels are advanced in a tentative, almost apologetic, manner, leaving the reader with a feeling of frustration.

In conclusion, I should like to raise questions on a few specific points. Why Gernica (Gernika) (p. 8) when the form Guernica has been made familiar by the Spanish Civil War and Picasso's picture? Why "Pluto, the god of Hadea" (p. 19) when Hades himself is a god? Why Isodorus (p. 19) for the more correct Isidore (of Seville)? "Tripodos" (p. 46) is not the genitive of "tripos." I find no such word as "specio" (p. 48) meaning "look" in Harper's Latin Dictionary.

In spite of all these criticisms, Professor Elderkin's book is rich in linguistic imagination and lexical material. It should be useful to scholars.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

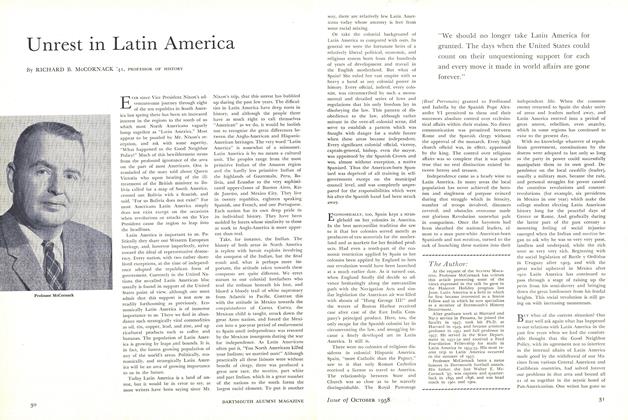

FeatureUnrest in Latin America

October 1958 By RICHARD B. McCORNACK -

Feature

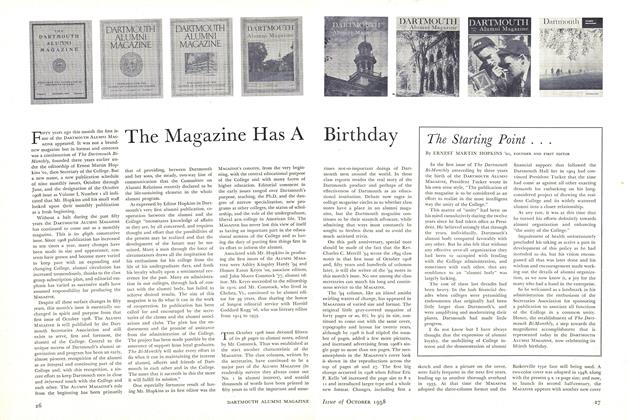

FeatureThe Magazine Has A Birthday

October 1958 By C.E.W. -

Feature

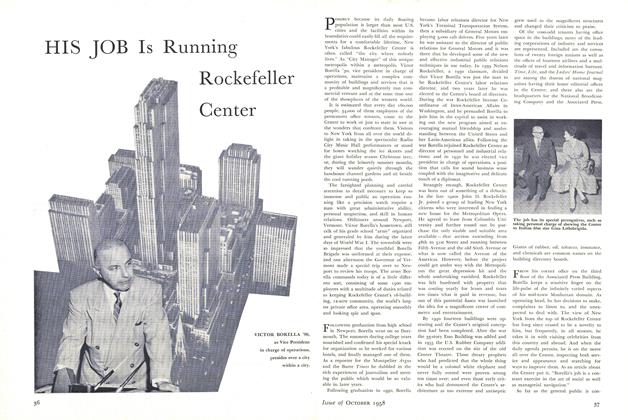

FeatureHIS JOB Is Running Rockefeller Center

October 1958 By JAMES B. FISHER '54 -

Feature

FeatureIndependence in Learning

October 1958 -

Class Notes

Class Notes1953

October 1958 By LT. FREDERICK H. STEPHENS JR., CHARLES B. BUCHANAN -

Class Notes

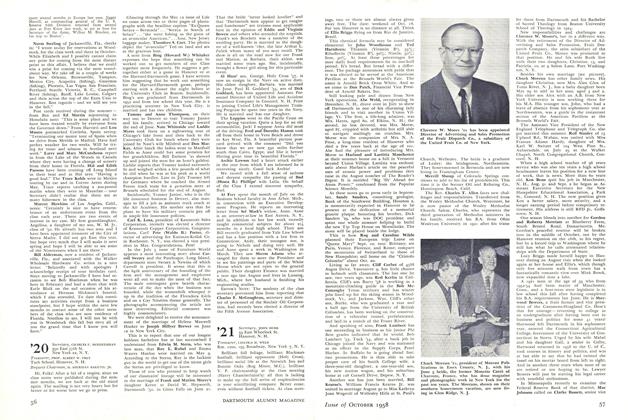

Class Notes1921

October 1958 By JOHN HURD, LINCOLN H. WELD

ROYAL C. NEMIAH

-

Article

ArticleMAY 3, 1923

June, 1923 By Frank L. Janeway, Francis J. Neef, William K. Wright, 3 more ... -

Books

BooksTHE LIFE OF ALCIBIADES

FEBRUARY 1930 By Royal C. Nemiah -

Books

BooksDAS DEUTSSCHE DRAMA IM AMERI KANISCHEN COLLEGE-U. UNIVERSITAETS—THEATER

May 1938 By Royal C. Nemiah -

Books

BooksFaculty Publications

July 1951 By Royal C. Nemiah -

Books

BooksAESCHYLUS, ORESTEIA

July 1953 By ROYAL C. NEMIAH -

Books

BooksDOCTOR WELLS OF VERMONT.

By ROYAL C. NEMIAH

Books

-

Books

BooksAlumni Articles

JANUARY 1970 -

Books

Books"The Geology of New Hamshire"

December, 1925 By E. D. E. -

Books

BooksWINSLOW HOMER.

JANUARY 1973 By HELEN MORSE -

Books

BooksShelf Life

May/June 2003 By Matt Feinstein '04 -

Books

BooksTHE GOOD PHYSICIAN.

JULY 1963 By S. MARSH TENNEY '44, M.D. -

Books

BooksSAINTS ON MAIN STREET.

March 1960 By THOMAS S.K. SCOTT-CRAIG