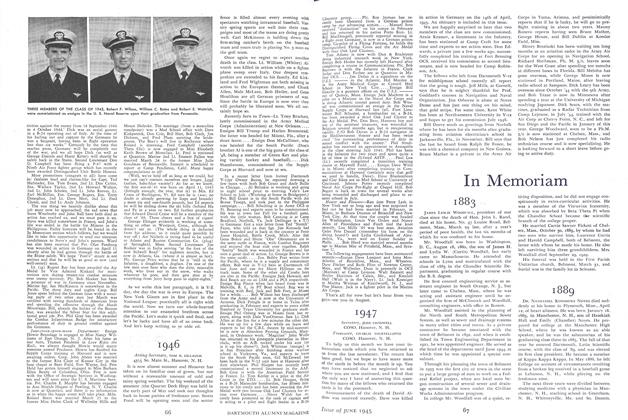

Letters from Dartmouth Men in the Armed Forces

From a foxhole on Okinawa came thefollowing letter written on April 28, 1945, by LT. MERRILL F. MCLANE '42, USMCR.

I have just received the March issue of the ALUMNI MAGAZINE which, needless to say, makes very enjoyable reading. It has started me again on an old train of thought that every Dartmouth man at some time or other toys with—namely, the making of a better Dartmouth. So I've decided to write a few suggestions toward that end. Maybe you can pass some of them on. I've been out of college three years now which should give me some perspective.

Before I begin I am going to give some alibis on this letter. I am literally writing in a fox hole, although it is made more luxurious by a shelter half and poncho erected over it, and a bed of pine boughs. You see, the island is by no means secured. Here goes:

A—ADMISSIONS—

(a) Continue to admit boys from all sections of the country, especially the South.

(b) More scholarships for poor boys, and not just to athletes and scholastic wizards.

(c) Admit more negroes and second generation Poles, etc.

(d) Let's have exchange students with foreign countries. After the war Dartmouth should have from 50 to 100 students in Europe and South America. Have them go after their sophomore year.

B—CURRICULUM—

(a) Continue the liberal arts courses, but after second year more freedom for selecting courses. Not so much emphasis on "majors." More "fellows." Let students follow a special interest even if they are not "B" or "A" students.

C—FACULTY

(a) Retire the "dead heads"—the professors who have outlived their usefulness as instructors. Some younger men fall under this category, too.

(b) Encourage and hire more younger men with fire and drive.

(c) English department is excellent, but can't we have more authors and poets like Robert Frost residing on the campus to give an occasional lecture? Dartmouth has too few visiting intellects to give informal lectures.

(d) Enlarge the music department with more courses for the layman—not technical. Include a course on popular music; why not study Duke Ellington and others as well as Wagner and Beethoven?

(e) More art courses—there were only two that were for the average student when I was in college.

(f) Continue intimate relations between faculty and students.

(g) Have older members of the faculty occasionally attend a class in, let us say, sociology or education. High school principals do it, why not in college?

(h) An accredited course in nature study—a very general one.

MORE THOUGHTS AT RANDOM:

Golf clubs, ski equipment, etc., available—perhaps rent them to needy students.

A bus to carry students out to Occom Pond for skating and skiing in the winter, and golf in the summer.

A big house for Alumni who return to Hanover—rooms at reasonable rates. Something like a flop house. Of course I can hear the Hanover Inn's comments at this suggestion.

Enough for now. I can't say anything about this island as yet.

LIEUTENANT RUSSELL HARTRANFT JR. '42, USNR, writes from the Pacific. Heis gunnery officer on a new U. S. destroyer.The letter is dated March 7, 1945.

At sea on the has been nothing but a continuous non-stop around-theworld cruise without any of the fancy enticements pictured on the travel posters. This past eighteen months has brought us over two-thirds of the way around the world with most of our tracks retraced many more than several times.

And now as we near the end of our long trail across the seas, the going has reached its toughest stage. The contest in the Pacific on its final battle-ground has resolved itself into many weeks of sustained cruising on the same very few square miles of water, sleepless hard-work days and nights when one is never out of reach of enemy strikes, vast invasion armadas—a thousand ships or more, devastating naval bombardments, and the fanatical, inhuman attempts of the enemy to repel us. There is no formula for the Japs, never are their actions explainable on a rational basis.

The vast unbelievable might of our fleet's sea and air power is a great thing to be a part of (and to be on the right side of). Our pattern is fixed, wellplanned, well-rehearsed—bombardment, amphibious assault, total destruction of the enemy, and rapid construction of land-based air facilities with which to relieve the carrier-based air umbrella which makes all of this possible.

And now the ring has tightened to these volcanic islands within the eight hundred mile radius of Tokyo. Our network of air and sea bases reaches over the entire Pacific, making the sphere of our influence safe for as long as we choose to keep it so.

So the end is in sight. Our most modern units are on the firing line, and the old ghosts have come back to do their haunting. The war in Europe is in its climactic stages; British and American Atlantic forces are being added swiftly to our numbers out here. Thus I inadvertently find myself looking beyond the final victory to the "big job." The problem is one which does and will provoke much thought before its solution is entered upon

—and that entry will be forced very shortly. However, our generation is most fortunate in having a perspective which includes the mistakes made at the close of the first World War and the disastrous results.

The proper adjustment of our national community, and personal tempo of living after the peace—so that it is lasting, happy, and productive—will take good leadership and strong-willed men with singleness of purpose. The victory will only give us the right to organize the world on an allembracing and mutually beneficial basis which will insure every man the right to a happy home and a family, a future with opportunities whereby his ambitions may be realized, freedom of speech, worship, and art, and most of all the security of these things that all men may have faith in them and that they may be inherited by our children and their children in full measure.

There are plenty of good things in this world for all and enough sadness in the natural course of human life. We must realize the stupidity of purposely destroying the former and augmenting the latter.

LIEUTENANT CHARLES W. HOLSWORTH '43, USCGR, writing from thePacific, gives a few comments on the valueof College as he sees it in retrospect afterthe experiences of service life. An extractfrom his letter home follows:

It took me about one and one half to two years after getting out of college to really realize that there is something in liberal arts education. At the time I was in college I thought all the talk about liberal arts by President Hopkins and others was a lot of bull. All I wanted to do at that time was just get scientific facts and fill requirements for forestry school. When I graduated I knew plenty of facts and had details down cold. Of course, since then I have forgotten a lot of facts but they come back easily with a little review, just as I have forgotten my French but when I glance at a French book, as I did last night...., it comes right back to me What I am getting at in all this is—there is an indescribable something I picked up in college of which I am becoming aware. It is a sort of general intelligence—perhaps it might be labelled liberal arts—sort of a training to use my mind and to apply things I knew. When I left college I knew a lot of rather disconnected facts, but it wasn't until I studied for comprehensives that I really began to; organize all these facts into a complete picture. In the week I studied for comprehensives, I really got an overall view of Botany. I connected all the courses together and, for instance, I saw how something I learned about a disease in Plant Pathology course had effect on something I learned in Plant Reproduction. Now things I learned in Math tie in with things learned in an English course. But best of all, I think, I have a general intelligence which enables me to grasp diversified situations. For instance, when the Commander was away and I was in charge, several situations arose which one of the officers under me couldn't handle. He could do well anything he'd had experience in but couldn't cope with something new and different. I, for instance, was called away from M's one night to such a case and when I got to work was able to handle it because of my superior education Not that I'd take any different courses if I had college to do over again. I think I got just as much general intelligence in my courses as I would have in any English, philosophy, 20th Century thought or similar courses. I realize that I was stimulated to think by my courses and heard ideas of different students and professors, and also that there was more than just scientific facts in my Botany courses. The whole intellectual (not meant in its bad sense) atmosphere at college, the contact with other educated people and some real geniuses like Professor Hull (he was not just a scientist) did me a lot of good. Just attending college and living there, did me a lot of good, I'm convinced. Nothing can take its place. People sometimes ask me what I got out of college The natural answer is for me to say I received training for the forestry profession and prepared for forestry school. But there's something intangible, something I can't describe to anyone else that I got at college, too. What President Hopkins said made no sense to me then. Now I've had the experience and know.

CORRECTION: The letter in 'Round, theGirdled Earth (April issue) credited to Jack Petrequin '35 was actually written by Captain John F. Jewett '35, Medical Corps, AUS. My apologies to all concerned.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Article

ArticleDARTMOUTH'S RIVER

June 1945 By Alice Pollard -

Article

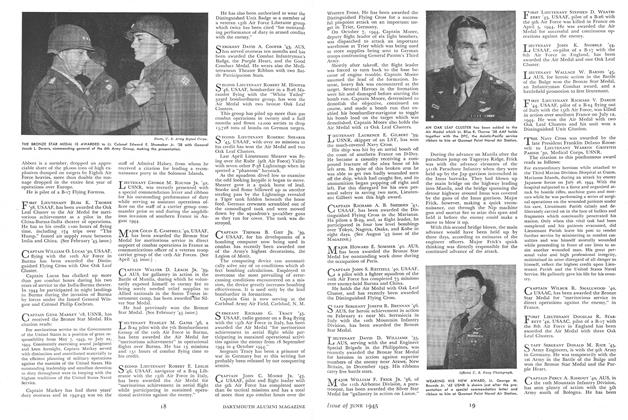

ArticleLaureled Sons of Dartmouth

June 1945 By H. F. W. -

Article

ArticleFOR MILITARY TRAINING

June 1945 -

Class Notes

Class Notes1918

June 1945 By ERNEST H. EARLEY, DONALD L. BARR -

Class Notes

Class Notes1945

June 1945 By ARTHUR NICHOLS -

Class Notes

Class Notes1908

June 1945 By LAURENCE SYMMES, WILLIAM D KNIGHT, ARTHUR BARNES

Lettter from the Editor

-

Lettter from the Editor

Lettter from the EditorCOMMUNICATIONS

January, 1926 -

Lettter from the Editor

Lettter from the EditorEDITORIALS COMMENT ON THE PRESIDENT'S OPENING ADDRESS

November, 1930 -

Lettter from the Editor

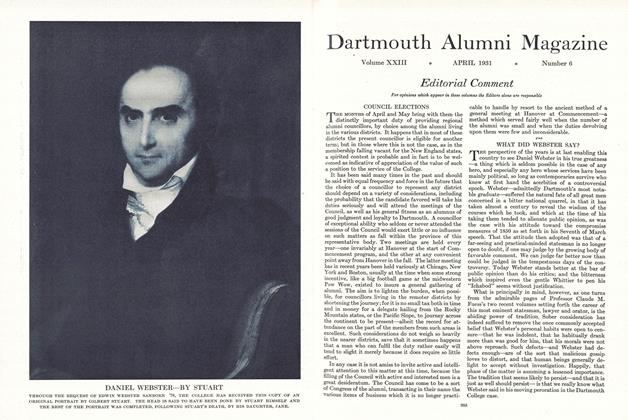

Lettter from the EditorEditorial Comment

April 1931 -

Lettter from the Editor

Lettter from the EditorMemoirs of a Great Editor

October 1937 -

Lettter from the Editor

Lettter from the EditorLetter from Oxford

April 1949 By CHARLES G. BOLTE '41 -

Lettter from the Editor

Lettter from the Editor75 and Counting

OCTOBER, 1908 By Douglas Greenwood