THE COLLEGE MIND

President Hopkins of Dartmouth has for some years accustomed us to look to his writings and addresses for frank and instructive views about college education today. Not an iconoclast or hot reformer, he is an intense educational realist, in the sense that he is always anxious to know what the facts are, what is actually happening in our higher institutions of learning, what young men and women are thinking, what can be done by professors and instructors to establish more inspiring and fruitful contacts with students. Yesterday, at the opening of the college year in Hanover, Dr. Hopkins spoke to the assembled faculty and undergraduates with a seriousness and force quite unusual in such welcoming exercises. He took for his subject "The College Mind," which he sought to analyze in its chief manifestations, complex and contradictory as these often seem to be. No one has more closely studied the ways in which the youthful intellect takes or rejects impressions and color when "exposed to culture," as President Wilson used to say grimly that some Princeton students had been without in the least being infected. But President Hopkins, after long and minute study of the various traits which enter into "the true portrait of the American college," thus limns it:

It would show a community in which generosity of spirit and graces of culture are predominant, where eagerness for wisdom and truth pervades the atmosphere, where the cooperative enterprise which we call education is carried on with mutual esteem and respect between faculty and students. It would likewise show, to be sure, some degree of self-seeking and self-indulgence, some effort to arrogate special privilege to individual selves, some pride of opinion, some intellectual arrogance and some close-mindedness, but these would appear, as they are, merely as blemishes upon the portrait. Each college generation has it within its power to refine or to smudge this portrait.

In urging Dartmouth students to seize upon every opportunity and agency for enlarging and strengthening their minds, Dr. Hopkins gave many of the old prescriptions but advanced certain fresh ones. He is as far as possible from being a formalist, and seems constantly to have before his eyes the fear that one good custom may corrupt the world. So he refuses to bind himself, and would not have college boys and girls bind themselves, by any "frozen" definitions of culture that have come down to us from the past. Useful and noble as these may have been, they sometimes fall out of touch with modern needs. It may well be that, while education is still mainly to be derived from literature and science and art and music and the established disciplines something should be added which can be got only from sympathetic understanding of the great movements going on in the world today. Even in the single matter of esthetic appreciation, Dr. Hopkins believes that American young men can get almost as much from observing our great buildings, our imposing bridges, our immense groupings of manufacturing plants, our vast schemes of reclamation, our multiplying and successful plans for making cities more beautiful and the country landscape more resplendent, as from mere attention to painting and sculpture and ancient monuments. His final conclusion is:

A new culture is growing up about us in America, not competitive with the old, but an extension of it, broader in scope, bolder in spirit, and more widely applicable to the needs of our common life. Herein lie new resources for esthetic satisfaction and spiritual inspiration. Herein lie new responsibilities for education. With all our getting in understanding, let us not fail in understanding this!

A DARTMOUTH VALUE

No student will ever be dropped from college because he has no feeling for landscape. It is a shortcoming that cannot be ranked in examination papers, perhaps fortunately, if a faculty happened to be of a Thoreau-like cast. There is not likely to be overemphasis on this phase of academic experience; indeed, it is so seldom mentioned that a few words on the subject by President Hopkins of Dartmouth in his opening talk to the undergraduates are quotable as a rarity:

I would insist that the man who spends four years in our north country here and does not learn to hear the melody of rustling leaves or does not learn to love the wash of the racing brooks over their rocky beds in spring, who never experiences the repose to be found on lakes and river, who has not stood enthralled upon the top of Moosilauke on a moonlight night or has not become a worshiper of color as he has seen the sun set from one of Hanover's hills, who has not thrilled at the whiteness of the snow-clad countryside in winter or at the flaming forest colors of the fall—I would insist that this man has not reached out for some of the most worth-while educational values accessible to him at Dartmouth.

It is probably not President Hopkins's desire that the students shall go about moonily contemplating the scenery. Dartmouth's traditions are as hardy as those of any college. Eleazar Wheeloek, her first president, relates in his journal that the college began in a log cabin eighteen feet square, around which his freshmen, forty red Indians, passed the winter in booths built of pine boughs which opened toward huge bonfires. From their campfires are descended those of the Dartmouth Outing Club, which makes sport of the hard New Hampshire winter. Dartmouth is a great outdoor college. President Hopkins has the Hanover perspective in putting that side of the institution well in the foreground. His thought is applicable to many other colleges of beautiful natural surroundings, which probably have their effect on most boys that are exposed to them, whether they are conscious of it or not.

DARTMOUTH TODAY

President Ernest Martin Hopkins of Dartmouth College has declared that "the primary concern of the college is not with what men shall do but with what men shall be." The spirit of that statement pervades the brochure just issued by the college in behalf of its Alumni Council. The publication itself is beautiful, written in simple and effective English, illustrated with remarkably handsome pictures, and printed in an artistic manner.

Scanning the booklet, we learn that the Dartmouth idea is to realize the cultural aims of the old liberal arts tradition rather than to emphasize especially vocational or professional lines of work. The school aims by the selective process of admission which became effective in 1921 to obtain its student body,, limited in number to about 2200, from widely distributed geographical areas, and today the boys come from 43 states and 13 foreign countries. We further note that "an interest in outside—or extra-curricular—activities has been shown by the majority of Dartmouth students in their preparation for college," and that these interests have been carried to the college campus. So, Hanover has not only the plant and equipment for thorough study, but facilities for development of hobbies, talents, and special interests of many kinds.

Dartmouth is peculiarly a New England institution. There is something especially appealing in the story of the removal from Connecticut to the upper New Hampshire by horseback, ox-team and on foot. Never will the famous argument of Daniel Webster be forgotten, the appeal that saved the school, "It is a small college but there are those who love it." For more than a century and a half the college has done its work well, and there are many outside its alumni who hold it in affectionate admiration.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Article

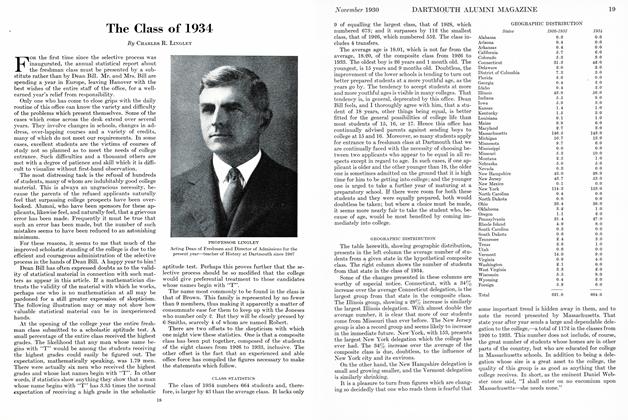

ArticleThe Class of 1934

November 1930 By Charles R. Lingley -

Class Notes

Class NotesCLASS OF 1930

November 1930 By Albert I. Dickerson -

Lettter from the Editor

Lettter from the EditorEditorial Comment

November 1930 -

Class Notes

Class NotesCLASS OF 1913

November 1930 By Warde Wilkins -

Class Notes

Class NotesCLASS OF 1920

November 1930 By Allan M. Cate -

Article

ArticleA Course in the Department of Biography

November 1930 By Harold E. B. Speight

Lettter from the Editor

-

Lettter from the Editor

Lettter from the EditorEditorial Comment

JANUARY, 1928 -

Lettter from the Editor

Lettter from the EditorEditorial Comment

MARCH 1930 -

Lettter from the Editor

Lettter from the EditorEditorial Comment

APRIL 1930 -

Lettter from the Editor

Lettter from the EditorNew Hampshire Letter

APRIL 1932 -

Lettter from the Editor

Lettter from the EditorDartmouth Sea Dogs

March 1940 -

Lettter from the Editor

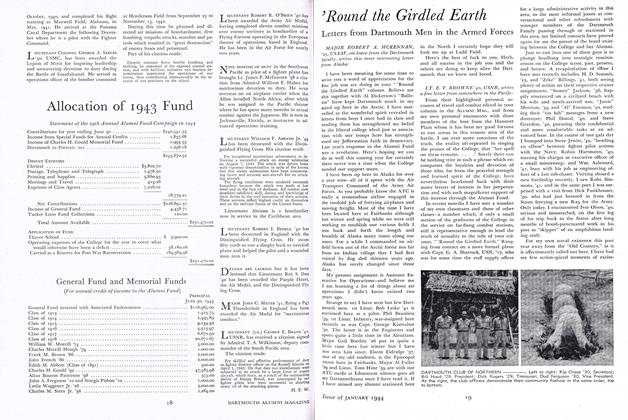

Lettter from the Editor'Round the Girdled Earth

January 1944