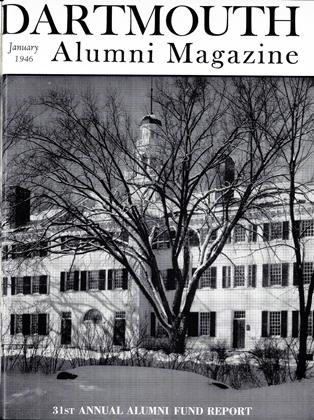

Dartmouth College Faculty Salutes Retired President

Following is the text of the resolution onthe retirement of President Ernest MartinHopkins, adopted by the Dartmouth College Faculty at its November meeting. Itwas read by Prof. Leon Burr Richardson'oo, who served as chairman of the specialcommittee which drew it up.

UPON THE RETIREMENT of ERNEST MARTIN HOPKINS from the presidency of Dartmouth College, after long and highly effective service, the Faculty of the institution places upon its records its sincere appreciation of the value of that service and its admiration for the personality who, for so many decades, has been the center around which the life of the College has turned.

No President of Dartmouth, no President of any college, has more effectively combined in himself the diverse and sometimes contradictory qualities demanded by the almost impossible requirements of the college executive. A leader of vision and resource, he has come to occupy a position in the front ranks of those who have the educational progress of the country in charge. High prestige among the undergraduates he soon acquired and has always retained, and, of far greater importance, he has always possessed their respect, confidence and personal affection. Without effort he has retained the unwavering confidence of successive Boards of Trustees as a result of qualities among which business capacity and financial acumen were not the least. With Dartmouth Alumni he has held a position of influence and a depth of personal affection perhaps unequaled in alumni relationships by any college executive of his time. His value to the institution has come to be considered by the college constituency—the parents and friends of the undergraduates—as perhaps the greatest of its assets. And his utterances upon educational, social and political problems are regarded by the public at large with keen attention, consideration and respect for their thoughtfulness, their wide background of knowledge and experience, and their sane idealism.

It is with his activities as an educational leader of the College, however, that the Faculty has had most to do. Upon his advent to the presidency in 1916 the number of active teachers was about 135; upon his retirement in 1945 it had increased to 275. Of the men now active in teaching, but 33 were in the service of the College at the beginning of his administration. More than nine-tenths of the present Faculty have known only him as head of the College. Even the remainder have passed the majority of their years of teaching under his leadership.

That this is true has been and is a matter of constant self-congratulation to the teaching body of the College. Each of us has regarded himself as highly fortunate that his lot has been to serve so long under so friendly and so effective an executive. The time of his presidency has been a period of change and rapid progress. Alterations in the routine of the College—change, even, in some of its fundamental methods and purposes—have been imperative. Most of the modifications and of the new methods have been initiated in suitable season by the foresight of the President himself, and have been developed, with time for leisurely consideration, well in advance of the pressing necessity for immediate action. With a flair for the choice of men adapted for definite types of work, often seeing in them qualities which they themselves were unconscious of possessing, he has entrusted the development of policies to selected persons who were given full responsibility for the performance of allotted tasks, who were assigned adequate facilities for doing these tasks effectively, and who received his steady and sympathetic support. Seldom were such efforts without fruitful result. To the deliberations of the teaching body he has brought a full recognition of the virtues of the academic point of view and full support of the aims of the professional educator, but he has also brought to them an acquaintance with and an appreciation of other points of view, by the application of which the academic approach to the solution of problems has been strengthened and broadened. Never using the authority of his position to impose the enactment of measures which he favored, if by argument and persuasion he failed to secure their adoption, with regret, but without repining or resentment, he acquiesced in their abandonment.

If painful necessity arose he could be decisive, exacting, even ruthless, but his general attitude was one of patience—the patience, perhaps, of a naturally impatient man in full control of himself. To a most remarkable extent he has had the capacity of getting things done. With him desirable projects involving expenditure upon first suggestion have never encountered, as an instinctive personal reaction, the vain regret that they could not be carried out because of their cost; but rather, the immediate consideration of ways and means by which they might be brought to fruition. And, in a multitude of cases, the ways and means were found. His insight into pressing problems has never been hampered by reservations and inhibitions, coming from dogmatism and preconceived ideas. He has always been courageous in the expression of his opinions concerning issues in which he has believed, whatever might be their unpopularity, and has insisted upon equal freedom of expression for all members of the College family. Most of all, he has been enthusiastic for Dartmouth and for all connected with the College—an emotional bond which has characterized his connection with the institution from his earliest undergraduate days, the inspiration which has been the motive force of his activities during his long service to the College which he loves. Much of the progress of Dartmouth during his administration has been due to his belief in her inevitable destiny—to his confidence that she was created and nurtured to be great.

Nor can the personal qualities of the President be ignored in this appreciation of his efforts. In his association with men, the tact which he has always shown is not a tact that has been developed consciously as an administrative asset; rather, it is the spontaneous and natural reaction of a friendly mind. For he is instinctively friendly, he likes men, he values association with them, he creates good companionship and responds to it. Never imposing the prestige of his position upon others, he meets all men upon equal terms, with simplicity, humor and kindliness. Devoid of pose or pretense, very soon he comes to be regarded by those with whom he associates, officially or otherwise, as a sympathetic and kindly friend.

For all these reasons the retirement of one who for so long has been the very heart of the College, when first announced could but fill with dismay those who cherish the institution. But his work, like the work of his predecessors, will remain, forming the basis upon which, we are confident, the future Dartmouth will rise to even greater heights. We are happy that in his retirement he still remains with us in Hanover, no longer the college official, but always the kindly associate, the helpful friend. We wish for him and for Mrs. Hopkins all the satisfactions that come from well-earned leisure and freedom from responsibility; we wish for them health an happiness in all the years to come.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Article

Article"THE LOOSE-ENDERS"

January 1946 By ALICE POLLARD -

Class Notes

Class Notes1918

January 1946 By ERNEST H. EARLEY, DONALD L. BARR -

Class Notes

Class Notes1945

January 1946 By ARTHUR NICHOLS, JOHN W. CALLAGHAN -

Class Notes

Class Notes1917

January 1946 By MOTT D. BROWN, DONALD BROOKS -

Class Notes

Class Notes1928

January 1946 By LT. OSMUN SKINNER, BRUCE M. LEWIS -

Class Notes

Class Notes1941

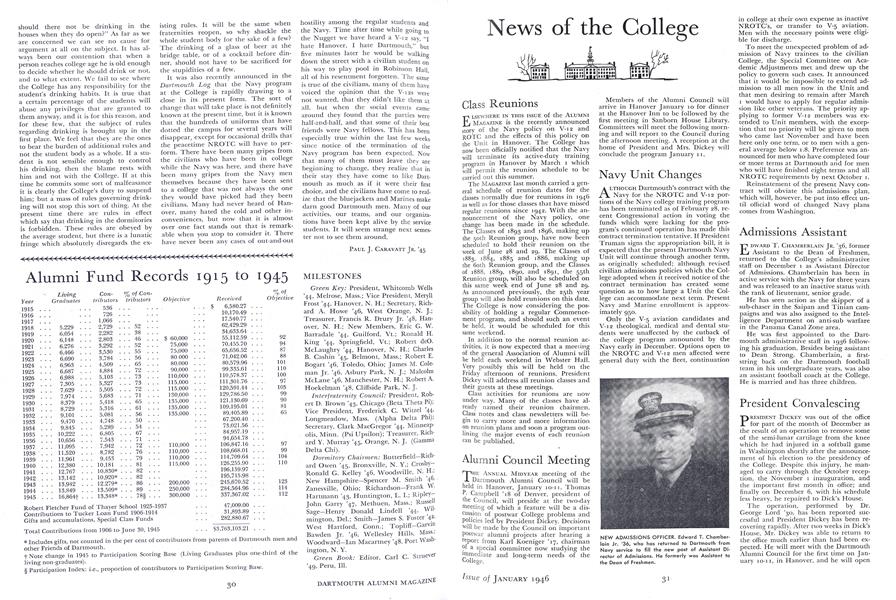

January 1946 By VINCENT R. ELSE, LT. PETER M. KEIR