THE first half of the 1979 football season was a disappointment for Dave Shula. As a sophomore, the split end from Miami Lakes, Florida, was a first-team all- Ivy selection and set three Dartmouth pass receiving records as the Big Green notched its eleventh championship in league play. Through the first four games of the current campaign, Shula had caught only 13 passes for 154 yards, and Dartmouth was still winless. The Green was blanked, 16-0, by Princeton in the home opener, tied the University of New Hampshire, 10-10, at Durham, lost, 13-7, to Holy Cross at Memorial Field, and was once again shut out, 3-0, by Yale at New Haven.

Dartmouth's offense had produced its only points in the UNH game: a seven-yard pass from quarterback Jeff Kemp to Shula and a 29-yard Chris Sawch field goal. The Green's defensive unit accounted for the other lone touchdown when linebacker Rich Salchunas grabbed a tackle-forced interception and raced for 70 yards and six points to close out the first half in the Holy Cross game. The absence of offensive consistency gave Dartmouth its worst start in two decades. The team had not been held pointless twice in a season since 1960 when, coincidentally, Yale and Princeton blanked the Green.

"It's caused by a lot of different factors," says Shula of the team's slow start and offensive difficulties. Inexperience at the quarterback position, injuries, and a breakdown of the offensive line have all contributed to the decline of the defending Ivy League champions. Coach Joe Yukica started Kemp, a junior, against Princeton and alternated Kemp, senior Larry Margerum, and junior Joe McLaughlin at quarterback against UNH. Against Holy Cross, six starters in the first game were sidelined with injuries. Kemp had 18 stitches in his chin and Margerum had mononucleosis, so the starting assignment went to McLaughlin, who saw varsity action last year as a defensive back. Kemp returned as a starter against Yale but completed only five of 17 passes for 31 yards, and the highly touted defense of the unbeaten Yale team held Dartmouth to 53 yards on the ground in 31 rushing attempts.

Shula says the shuffling of quarterbacks shouldn't affect his performance. "I run my route the same every time," he observes. Shula concedes, however, that if a passer and receiver know each other very well, they will be more successful when the onrushing defensive unit forces the quarter- back to scramble in the backfield. "It just takes time," he says of the passer-receiver relationship. "A team that is blitzing a lot puts a lot more pressure on the quarter- back. It really screws up the timing." Shula had a special affinity with Buddy Teevens, last year's star quarterback who graduated in June. "Buddy was just tremendous," he says.

The sure-handed Shula became the team's principal receiver because he always seems to be open in passing situations. His phenomenal 1978 season included 49 receptions, which was nine more than Harry Wilson's 1976 record. Those receptions accounted for 656 yards, ten yards more than the other receiving mark previously held by Wilson. In the Princeton game that clinched the Ivy title, Shula set a single-game reception record of 191 yards to eclipse Tom Fleming's 1976 standard of 173 yards. His eight receptions against the Tigers, one for a touchdown, was only three shy of tying still another Dartmouth record. For his efforts against Princeton, Shula was named Ivy League player-of- the-week and ECAC rookie-of-the-week. He takes the personal statistics and accolades in stride. "My only goal is to play the best I can and help our team win the Ivy League," he says. "Anything else that comes with that will be gratifying, but the team always comes first."

Shula is the son of Miami Dolphins coach Don Shula, who has guided his National Football League club to two Super Bowl victories since 1970. Dave worked for the team during its training camp and frequently played catch during warm-ups with the players, although he never worked out with the club. "Just being around a lot of great players helps," he says. "And Dad has always been there when I've needed any encouragement and advice," he says of his father, who has been unable to see his son play because of conflicting weekend football schedules.

The Floridian ended up at Dartmouth because of Lou Maranzana '70. When Shula was a senior at Chaminade High School, Maranzana, an English teacher, asked him if he had ever considered going to an Ivy League school. "I had never thought about it, but I came up to see the school, liked it, decided to give it a try and apply, and here I am," Shula recalls. "It was the toughest decision I had ever made." That decision caused a stir in his home state because Shula, a defensive back and split end in high school, had accepted a non-binding scholarship .at Florida State.

"I guess they were a little surprised I decided to switch," he says. "But I decided that my education was more important than playing football year-round. In high school, I played baseball in the spring and wanted to continue that. I know now that I made the right choice. Here, I play football just in the fall and can concentrate more on my studies during the winter and spring."

Shula hasn't had any trouble adjusting from a Florida to a Hanover climate, although he admits playing in the snow "may be a bit drastic." He is majoring in history. This winter he will be working for a congressional committee in Washington and will live with teammate Kemp, whose father Jack is a congressman and former quarterback with the Buffalo Bills of the American Football League.

"My main interest will always be football," the 5-foot 11-inch, 175-pound junior points out. "I do enjoy playing two sports, however, and will be out for the baseball team in the spring." Is professional football on the horizon for the son of a NFL coach and former player? "I try not even to think about it," Shula explains. "Some days in practice I can't even get open during one-on-one drills; I drop passes and I'm not too fast. I just try not to think about it."

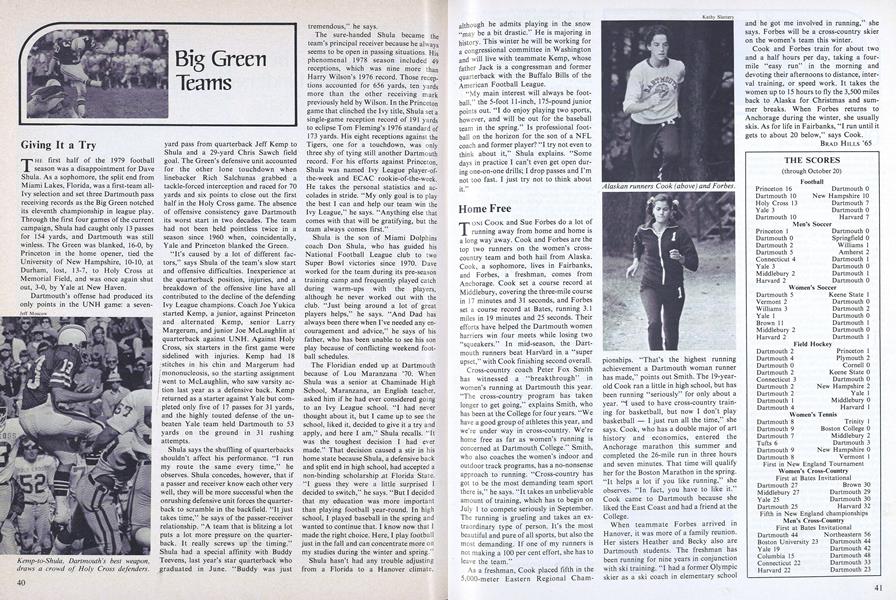

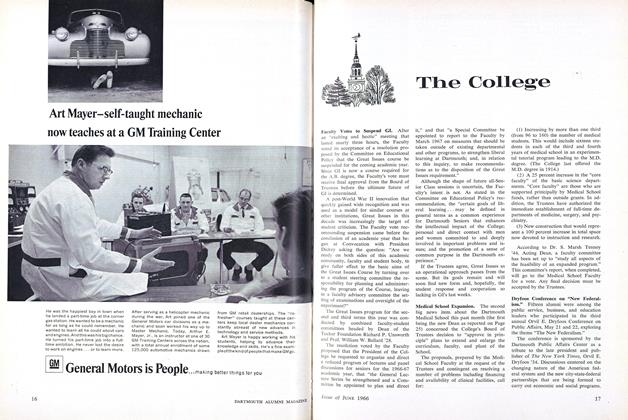

Kemp-to-Shula, Dartmouth's best weapon,draws a crowd of Holy Cross defenders.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

FeatureUncle Sam and Mother Dartmouth

November 1979 By Dan Nelson -

Feature

FeatureIt's Where We're Coming From, Citizens

November 1979 By Jeffrey Hart -

Feature

Feature'A need for someone who holds my views'

November 1979 By William M. Hill -

Article

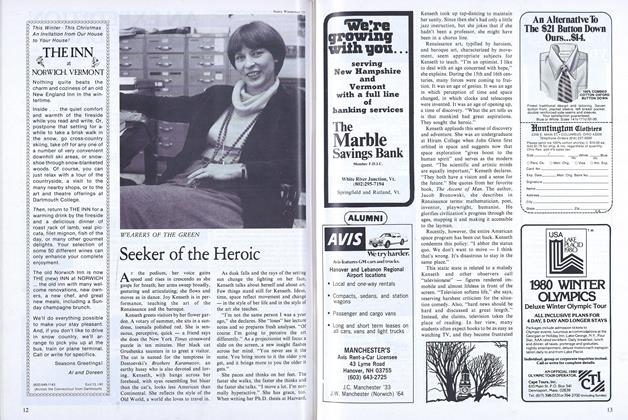

ArticleSeeker of the Heroic

November 1979 By Beth Baron '80 -

Article

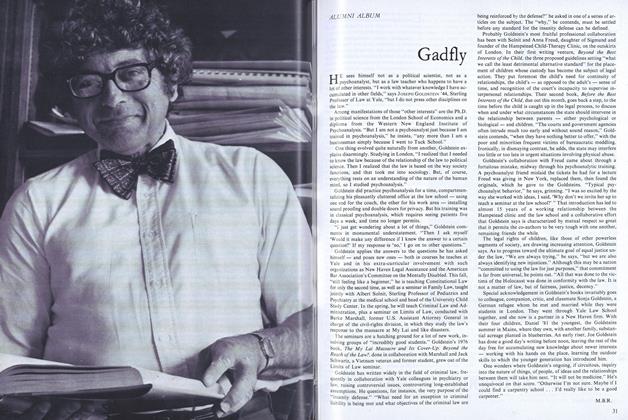

ArticleGadfly

November 1979 By M.B.R -

Article

ArticleA Little More Anarchy, Please

November 1979 By Bruce Ducker '60