A Veteran Concerned

TO THE EDITOR:

I am writing as a veteran concerned with his own problems in our present society but I think that sometimes one can see the forest

from its trees. This is just the first paragraph of the most recent of several letters from different recruiting agencies in Navy:

"What are the most important qualities 111 a civilian job to a man with a family? Think a minute, and you will realize, as I did after two years of practicing law, that they are opportunity, pleasant working conditions and most of all . . . job security. A man's family must be secure before he can think of himself."

Many of us are just out of the service a short while, many just getting out. All have been subjected to a new type of life in the past four or five years—a type of existence in which there were several factors that were unique.

We were placed in an ordered, well defined social group. We were organized into a type of existence that offered security in exchange for personal liberty in varying degrees. We were part of an organization that gave us social and economic positions with shape, simplicity and order.

Being scions of free enterprise and products of social institutions that still accented individualism, we groused and rebelled within a framework that still carried mass social approval and economic security.

Now we are cast back into the "free" society and many of us are beset with problems. We are attacked with letters from the War or Navy Departments accenting their features of social and economic security.

We have, many of us, acquired families and we are older. Idealism comes harder with age. Nationalism has become International and nations are interdependent. We begin to feel the size of society and the ponderous forces that dwarf us. We get an inkling of what Huxley's native felt in "Brave New World" when his only rebellion was self-flagellation.

We are tugged by the two forces—security and a personal, idealistic striving. If we are purely economic creatures, we can reduce our choice to dollars and cents; if social—to traditions, pensions and social acceptance. We admit we have to live with ourselves and we hate to consider that we may be a social parasite performing a somewhat negative function. But, we consider our families and suppose that two years afloat and four years ashore will not be too painful.

We have our idealistic and our practical side and this period of transition is one in which we are assaulted with choices: adventure with a family or security without adventure.

It is a period in which we are subjected to grave doubts. It is a personal problem and yet it reaches into seven million lives in varying degrees.

I'm back at school. It is a hard decision to hold to eight years after graduation. It is particularly hard in the face o£ more separation from family because of impossible living conditions here.

Against the background of depressions, of average college graduates' incomes, the squeezing $9O per month with rising prices and consequent depletion of family savings it is not easy to maintain ideals. The problem of readjustment is one any veteran has to face. Those of us who retain our belief in a free society and in our ability to produce a greater security for others are making and holding to our decisions in the face of some disruptive forces.

I feel that we can contribute to the peace. We must have a positive belief in that and a personal integrity and grasp of ideal to do it. This is one veteran's problem. It should be common to many. This is a hard period for us. Many need understanding and reinforcement. I believe this is the job of an aggressive faculty and a liberal college.

We are coming back to school in a time of transition and in an effort to shape our lives and our ideals. We are different but not yet jaded. We don't want any part of a "lost generation."

Some colleges are looking for a return "to normalcy" after the period of upheaval. This is not a cyclical but a secular change. It is reassuring to see that Dartmouth is making a real effort.

Cambridge, Mass.

Responsive Ears

To THE EDITOR:

My attention has been called to the letter of Mr. William T. Adams '34 in your March issue in which he expressed the wish that Dartmouth might do more to encourage alumni and others to contribute towards the development of the permanent art collections of the College.

The fact that you printed this letter suggests the propriety of using the same vehicle to remind Mr. Adams (and any other alumni who may be similarly uninformed) that the liberal arts curriculum of the College not only "embraces, among other things, a beginning appreciation of art"—but has been offering a regular major in the subject since as long ago as 1928—and that we do have a quite respectable teaching collection of original works of art representing all mediums of expression and many periods which we hope will continue to grow in size and usefulness as time goes on.

The larger part of this collection has been acquired since Mr. Adams was in college. It is not yet large enough to require a separate museum building to house it but that will doubtless come in time. Indeed Mr. Adams' letter is a most heartening straw in the wind; for no comparable institution depends more than Dartmouth on the interest and devotion of its alumni in this as in other important elements in the growth and prestige of the College.

On behalf of the Department of Art and Archaeology I wish cordially to thank Mr. Adams for his letter and to assure him and any other alumni who may have constructive ideas for improving the art resources of the College that their suggestions will not fall on unresponsive ears.

Chairman, Dept. of Art and Archaeology

Hanover, N. H

Not Typical

I should not want readers of the April ALUMNI MAGAZINE to assume that the opinions expressed by Professor Keir in his article on Labor were typical of those held by other members of the Department of Economics. I do not agree with the conclusions in the last two paragraphs.

Hanover, N. H.

Hanover Episode

To THE EDITOR:

A classmate of mine, Ned Dearborn, tells "some remarkable tales of the apparent intelligence and the indubitable skill of various animals in his Accretions of a Minor Naturalist; among them how the seagulls drop clams from a considerable height upon stones in order to break the shells and get at the meat. I too have seen where shells have been dropped upon stones not over a foot in diameter. Only the mathematical precision of a bomb-sight would enable a human being to do this in flight.

I have, moreover, seen the equal of this in intelligence, if not in skill, in the course of a recent episode. Between the spot where I was sojourning for the summer in Hanover, N. H., and the Dartmouth stadium grounds there stands a high-bush hedge. A pair of birds have a nest there. Sometimes in the heat of the day I carry a chair out with a book or a magazine to read in the shade of a tall elm tree that rises close by. The birds flit to and fro and scold me vigorously.

So this time I scolded back. I spat at them: "You go to tunket. I shall stay right here." But did they stop? Not at all. They kept right on, and finally the big boy flew up and perched far above me on a branch of the elm. Peering down he squawked again at me, and again I retorted: "Go away. I won't move."

For a moment there was silence, and then he let go. He hit the mark, too, right on top of my bald head. I moved.

Intelligent creatures these Hanover birds. This comes perhaps from association with collegians.

New Brunswick, N. J.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Article

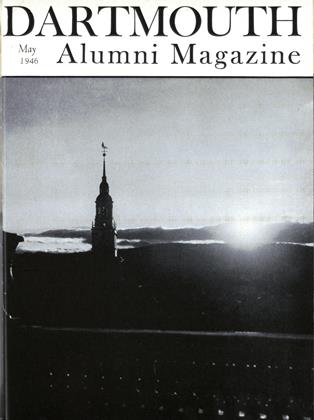

ArticleTHE WHITE CHURCH

May 1946 By PROFS. FRANCIS LANE CHILDS '06 and ERNEST BRAD LEE WATSON '02 -

Article

ArticleMedical School

May 1946 By Rolf C. Syvertsen M'22. -

Article

ArticleTwo Commonwealths: One World

May 1946 By THOMAS S. K. SCOTT-CRAIG -

Class Notes

Class Notes1918

May 1946 By ERNEST H. EARLEY, DONALD L. BARR -

Article

ArticleThe Role of the Humanities

May 1946 By ARTHUR M. WILSON -

Article

ArticleJESS B. HAWLEY '09

May 1946 By SIDNEY C. HAZELTON '09