THE AVIDITY WITH WHICH the returning veteran is pitching into his studies including those in the humanities is an intensely stimulating phenomenon. So stimulating that we teachers sometimes wonder, especially after digesting Andrew M. Scott's remarks in the March issue of the ALUMNI MAGAZINE, whether we are quite capable of measuring up to such great expectations. We are, at all events, trying to, for there among the students sitting before us—every teacher here is having a comparable experience—is a flyer shot down in France and rescued by the underground, a tanker who lost an eye on Saipan, a man who passed as a native and operated behind the German lines in Tripolitania, a man who taught English to Italian prisoners of war, a veteran who served in counter-intelligence in the Pacific, a pre-medic who served OSS in Cairo and Chungking, and another OSS man back from service in Kandy, Singapore, and Batavia. There they are, eager—gratifyingly eager—for learning, provided it be learning for a purpose. There is a new spirit abroad. It has even become difficult to find typographical errors in The Dartmouth! And, seriously speaking, if we faculty have the elemental sense to honor this new earnestness by expecting a great deal from it; if we can be steel to this flint, we can make the era of the returned GI a memorable one in the intellectual history of the College.

The earnestness and seriousness of the veteran is not unnaturally combined with deeply cherished views on what a college education ought to be, views which he sometimes expresses with startling candor. I therefore find myself, in my attempt to answer the editor's request for an estimate of the role to be played by the humanities in the atomic age, analyzing or speculating upon what the veteran thinks about the subject. My own conviction—a cheerful one—is that the humanities and the point of view imparted by a study of them are needed more than ever. And I think that the instinct of the veteran confirms this view. If so, this is a matter of great professional interest to us teachers, and of great interest also to anyone attempting to analyze the trends of thinking in our society. For the veteran is already influential, will become even more so, and, as Lincoln said of the common people, there are so many of him.

It was not many months ago when some educators and many journalists were predicting that the veterans' post-war educational interests would be almost exclusively technological. Well, it hasn't turned out that way, and the citadels of general education are being as much besieged by the returning veteran, as are the technical schools. It is obvious that a liberal education strikes the veteran as something extraordinarily attractive.

Now of course a large part of this attractiveness is really vocational, after all, especially for the thousands preparing for all sorts of professional and graduate schools. Moreover, the veteran gives one the impression, which I am sure is correct, that he is being quite unsentimental about the education he is receiving. He wants to get his time's worth, and he is not treating the GI Bill of Rights as though it were a boondoggle. His return to the campus is inspired by a hard-headed sort of self-interest which is entirely appropriate in the case of men who have already lost so much time. The veteran naturally thinks of his personal and individual needs first. The expectations which society may have of him come second. And why not? Society has already had the benefit of a good deal of his time.

Nevertheless, the veteran today will acknowledge a much greater social responsibility than he would before he went to war. I suppose that this too is just another form of enlightened self-interest. For he knows from hard experience that a free society has to be actively defended. It had to be on the battlefield, and it will continue to need defense inside people's heads. So the return to the liberal arts campus is, at least in part, a recognition of the responsibilities of citizenship, and signifies in part a sort of instinctive assumption that a general education will be helpful in warding off the chaos and destruction which constantly imperil our excessively dangerous age. And if you think I am fanciful in thus interpreting the distinctly serious and sober mood of the campus these days, let me remind you of those articles by undergraduates, published under the heading

"So Little Time" in the March issue of this magazine. For example, William H. Miller Jr. wrote therein that students "are painfully and gravely aware of the urgent need for new and valid ethics of living." Furthermore, the editorial in the first number of the revived Dartmouth flaunted the word "duty"—"lt Is a Man's Duty to Understand His World"—and in the third paragraph from the end referred to "our entire responsibility to ourselves and to mankind... ." We are used to college presidents and commencement speakers using words like "ethics" ancl "duty" and "responsibility," but when you have undergraduates doing it just any day in the week, you can be sure that they have begun to think pretty deeply about what ought to be humanity's reasonable expectations of our social and political and economic institutions.

It is at this point that the humanities, and the point of view which their study imparts, come in. For the humanities, vague as that term is and various as are the intellectual disciplines included in it, have sturdily stood forth through the ages as champions of the view that institutions should serve humanity and that we should not get the cart before the horse. The history of this point of view is a long and comforting one to persons confused, as who can help being confused, by the hurlyburly of contemporary events. And wherever, whether in a college or out of it, views are expounded and subjects taught which are based on the axiom that people are more important than things—to try to state the problem as simply as I know how —there is a writer or teacher who accepts the point of view of the humanities. Socrates would have recognized it, I am sure, as being a very proper concern with "the good".

The veteran seems to me to be thinking along these lines, although perhaps not all of them very articulately or consciously. If this is his line of thought, he is in this respect similar to the scientists who participated in developing the atomic bomb. These chemists and physicists have suddenly become our leading humanists. Reversing in an instant the detachment, not to say hauteur, with which they and their scientific forebears have regarded for the past three hundred years the implications of their discoveries, they have been almost the first to realize that the supreme and ultimate question about the bomb is not a scientific, but rather a humanistic, one. Can the bomb be disciplined so that humanity will be its master and not it humanity's? The desperately serious fashion in which the scientists are trying to warn their fellow-citizens of their peril seems to me to be symptomatic of a general determination, shared by the veterans and revealed by the kind of education they seek, that knowledge shall be judged not by itself alone but by its service to the welfare and destiny of humanity.

The atomic bomb is just one of humanity's problems, of course, albeit the most exigent one. There are others, and they all add up to a truly sporting proposition, for it is by no means certain that the cause of freedom and of humanity will prevail. As Andrew M. Scott said in his article, "the 'race between education and catastrophe' is at its crucial point." Will technology make slaves of us, or shall we be able to make technology subserve human ends, is one of the great unknowns. What may happen to us, even if we avoid sudden vaporization, could be something like the technocracy of Aldous Huxley's Brave New World. Similarly, there is always the danger of the tyrannical state. Leviathan may eat us all up, even though the British and American conviction that the state exists for man and not man for the state be a tenacious one. Everyone worries sometimes, and some people worry a great deal, lest there be fixed upon us somehow or other an American authoritarianism which will be none the less totalitarian for being "100 per cent American."

Talks with students have convinced me that we don't have to make a particular effort to alert the veterans on problems such as these (and I mention the veterans so much because they are setting the tone of the post-war college). They themselves are answering affirmatively the question of whether the humanities, and, indeed, the humanistic implications of all their stud- ies, have become more important in the atomic age. In consequence our students are a college generation interested in seeing that institutions, whatever they be, exist for the purpose of serving humanity instead of enslaving it.

Well, they are not alone in that. Their faculty here cherishes a similar determination. And so, surely, must the alumni and our citizenry in general. For, as Charles Bolte and his American Veterans Committee point out, the veteran is not a creature set off from his fellow citizens (although it may be true that with the sights he has seen still fresh in his mind's eye, he is more urgent about what must be done). The problem is the problem of all of us, and the more confusing because we cannot deal with these overpowerful slaves who threaten to become our masters by simply exiling them. We cannot get along without technology or the state, of course; but the difficulty lies in knowing at what point they become abusive and must be controlled.

The contribution of a faculty to the solution of this problem does not lie in the area of moral exhortation. Besides, from the way Dartmouth undergraduates are now acting—especially those who left Dartmouth to go to war and have now returned to finish out their college courses—it is obvious that they are aware, and that their hearts are in the right place. What a faculty can contribute is the clarification that comes from relating our several specialized subject-matters to the main purposes of life. We ought, moreover, in a critical and objective way to help our students to build up a reliable criterion which they can themselves apply to confusing situations. And what is this reliable criterion? I would venture to say that the criterion would be this: that what is truest to the nature of man is what is best for man—the whole man, both as an individual and as a social being. Liberal education, according to this view, is an exercise in humane letters in which the findings of science; the insights of poetry, religion, and letters; and the conclusions of social studies all converge upon the problem of trying to arrive at a critical understanding of the nature of man and of the ends of man. And to this Aristotelian purpose the four years of our college education should actively contribute.

Something like this, I should judge, is also the opinion of the veterans who wrote in the March issue. In addition, it is plain that the veteran has returned not only earnest and eager, but also critical. Among his virtues is a forthrightness not heretofore so publicly displayed. I have observed this new phenomenon in my own classroom, as I know my colleagues have done in theirs. And there was an extraordinary amount of it in the remarks of Andrew Scott, a young man who is evidently an enfant terrible in a quiet, Caledonian sort of way. (In justice to the faculty who stayed in Hanover during the war, let it be said in reply to accusations of staleness and lack of intellectual curiosity that the drain on faculty energy and vitality, as a result of continuous academic sessions since September 1941 and as a result of having to teach unfamiliar subjects, has been extreme). But as for Scott and his colleague Miller, had it not been for the impact of their remarks, you might now be reading from my pen a redeployment in force of the arguments as to why the humanities ought to be considered important in the atomic age. But I discovered in the nick of time that these gentlemen seem to have assumed as axiomatic all that I was about to adduce and seemed to be taking up at just about the point where I had intended leaving off, so you have been mercifully spared.

The give and take between faculty and students at Dartmouth has always been more than is common elsewhere, as I know from personal experience. And the challenging of the older by the younger keeps both from relapsing too comfortably into stuffed-shirtism. For years we have been telling undergraduates that this and that is their responsibility. Now, it seems, they are telling us what is ours. And what are they telling us, in effect? Is it not to speak out on great issues with more passion and conviction? Is it not to be positive on great issues, instead of just piling up a little heap of facts on the one hand and a little heap of facts on the other and then leaving them there to decay until we come back to rake them over the next time we give the course? Is it not that they are saying these things because they agree with President Dickey that there is so little time?

If that is what they are trying to say to us, who among us can refuse to take the lesson to heart?

WRITING FROM THE HUMANISTIC POINT OF VIEW, Prof. Arthur M. Wilson of the Biography and Government Departments asserts that institutions in the atomic age must serve man, not enslave him.

DARTMOUTH PHILOSOPHER. Prof. Thomas S. K. Scott-Craig of the Philosophy Department, who is less alarmed than some of his colleagues over possible danger to the world from atomic power.

Professor Wilson is a member of two Dartmouth faculty departments—Biog- raphy and Government. After eleven years "of teaching in the former he was named in 1944 to the Department of. Government, in which he will offer next term a course in The History ofPolitical Theory, utilizing some of the material of the war course Componentsof Democratic Thought which he directed. Professor Wilson returned to his teaching duties last November after serving for nearly two years with the OSS in Washington. Before coming to Dartmouth in 1933, rofessor Wilson was Instructor in History and Tutor in the Division of History, Government and Economics at Harvard. He earlier taught at Grinnell College and has been visiting professor at the Universities of Washington and Missouri. A graduate of Yankton College, he was a Rhodes Scholar from South Dakota from 1924 to 1927 and holds the 8.A., B.Litt. and MA. degrees from Oxford. In 1939 he received a Guggenheim Fellowship to write a biography of Diderot, French encyclopedist. One of the most scholarly of Dartmouth professors, he is also one of the most popular with undergraduates. In "Courses in Review" in TheDartmouth he has been described as "a subtle teacher."

PROFESSOR OF BIOGRAPHY AND GOVERNMENT

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Article

ArticleTHE WHITE CHURCH

May 1946 By PROFS. FRANCIS LANE CHILDS '06 and ERNEST BRAD LEE WATSON '02 -

Article

ArticleMedical School

May 1946 By Rolf C. Syvertsen M'22. -

Article

ArticleTwo Commonwealths: One World

May 1946 By THOMAS S. K. SCOTT-CRAIG -

Class Notes

Class Notes1918

May 1946 By ERNEST H. EARLEY, DONALD L. BARR -

Article

ArticleJESS B. HAWLEY '09

May 1946 By SIDNEY C. HAZELTON '09 -

Class Notes

Class NotesDartmouth Navy News

May 1946 By ARTHUR R. WILSON '47

ARTHUR M. WILSON

-

Books

BooksLA GUERRE D'UN BLEU.

October 1954 By ARTHUR M. WILSON -

Books

BooksTHE LITERARY ART OF EDWARD GIBBON.

June 1960 By ARTHUR M. WILSON -

Books

BooksHUMAN NATURE AND POLITICAL SYSTEMS.

November 1961 By ARTHUR M. WILSON -

Books

BooksTHOUGHTS FROM ADAM SMITH.

JUNE 1963 By ARTHUR M. WILSON -

Books

BooksPINE LAKE.

MAY 1972 By ARTHUR M. WILSON -

Feature

FeatureSelf-Evident Truths

May 1976 By ARTHUR M. WILSON

Article

-

Article

ArticleIndicted

Mar/Apr 2013 -

Article

ArticleREAD WORTHY

May/June 2007 By Carolyn Kylstra ’08 -

Article

ArticleThe Undergraduate Chair

MAY 1930 By Craig Thorn, Jr. -

Article

ArticleGREEN NOTES

DECEMBER 1968 By JACK DEGANGE -

Article

ArticleChampions

December 1978 By Joe Yukica, February 1978 -

Article

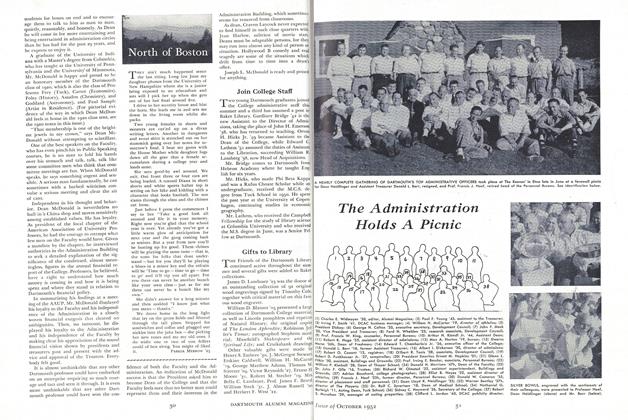

ArticleNorth of Boston

October 1952 By PARKER MERROW '25