Historic Church at Dartmouth Marks 175th Anniversary

IN AUGUST OF 1770 Dr. Eleazar Wheelock, his sturdy soul filled with zeal for the education of young men who would carry on his lifelong purpose of bringing the heathen Indian into the Christian fold, arrived with his workmen on Hanover Plain to begin his conquest of the wilderness and to build his infant college for which, after years of strenuous effort, he had then recently obtained a royal charter. In September he was joined by Madam Wheelock, her household retinue of children, servants, and negro slaves, and the two score youths, red and white, who were to constitute the first student body of Dartmouth College.

Even in the midst of those busiest days of bustle and toil to fell trees, erect shelters, and conduct classes, their leader's sincere piety and holy purpose so permeated the little group that a notable revival of religion sprang up among the students, and Dr. Wheelock recorded in his diary for 1771 these words: "The 23rd of January was kept as a day of solemn fasting and prayer, on which I gathered a church for this college and school, which consisted of 27 members .... and a solemn and joyful day it was." This group of 27 was made up of members of Wheelock's immediate family, two or three employees of the Indian school, and sixteen students; in other words, it was entirely a family affair, but from that small and intimate beginning has grown the strong and active church that has served for 175 years as the chief religious light of Hanover; and that little room in a rude frame structure on what is now the southeastern corner of the campus green, in which the Church of Christ at Dartmouth College was gathered, is the lineal ancestor of the beautiful building in which the church serves and worships today.

Wheelock's church was gathered independently, without the aid of a council, yet was intended to be Congregational in form. Two years later, however, through Wheelock's efforts, the Grafton Presbytery was set up, and for the next thirty years the Church of Christ was Presbyterian.

Eleazar Wheelock, who headed everything with which he was concerned, as a matter of course and presumably without any formal vote, served as minister of the little but rapidly growing church until his death in 1779. He was succeeded in his pastoral duties by his son-in-law, Rev. Sylvanus Ripley, who had been graduated in Dartmouth's first class, had been ordained as a missionary to the Indians, had served as chaplain in the Revolutionary Army, and had developed into a strong figure in the community and the school. In 178s he was elected by the Trustees as Professor of Theology. He is said to have been a kindly, genial man, loved by all who knew him, and under him the church continued to grow, eighty members being added in four itionths in 1781-82. Mr. Ripley came to a sad and untimely end. Returning in a raging blizzard from preaching at Hanover Center, he was thrown from a sleigh in Etna village on February 5, 1787, and died of a broken neck.

From 1783 on, Mr. Ripley had been assisted in his pastoral labors by Rev. John Smith, Professor of Learned Languages in the College. Upon the former's death, the College was too poor to engage another professor of divinity, whose duties would have included that of preaching to the students and community, and the church therefore invited Professor Smith to become their sole minister. This invitation was renewed annually until 1804, although both Mr. Smith and the church were not entirely satisfied with the arrangement and expected it to terminate whenever a qualified professor of divinity should be appointed to the vacant chair.

Mr. Smith appears to have been a good but weak man. He was a pedantic scholar, who wrote grammars of the Hebrew, Chaldee, Latin, and Greek languages, who taught by rote, and who preached, we are told, without force or animation. Moreover, although weighing over two hundred pounds, he was physically timid, mentally nervous, and totally subservient to the domineering President John Wheelock. Under him, except for the building of the old white meeting-house, the church marked time. His home, which he erected on the lot where the Precinct Building now stands, long since passed away, but his name, like that of Ripley, is attached today to a college dormitory.

Until 1790 the church had held its services in the old College Building on the campus, opposite the site of Reed, which was used also as commons and chapel. In that year a separate chapel had been erected near where Thornton now stands. It may be plainly seen in the earliest views of the College—the Dunham engraving and the Ticknor drawing.

This was the first separate building used by the Church of Christ. The Parish had shared with the College the cost of its erection. It was said to be "a perfect whispering gallery." Across its sixty foot diagonal expanse the "ticking of a watch could be heard." We read also that "it was never profaned by a stove." Neither was it profaned by any manner of student use except for religious, musical, or oratorical purposes.

Of the many unique Dartmouth customs long since forgotten, there was none more amusing than the strange practice of students at prayers. At the first word of a prayer, all rose, turned their backs to the preacher, and sitting on the back rail of the pew in front, planted their feet on the seat from which they had risen. This back-to, chicken-roost praying, believe it or not, continued until 1871, when as a writer in the Aegis reported: "At prayers we have ceased to turn like devout Mussulmans toward the chapel organ." Whether students attending church services chickenroosted during prayers is not stated. It seems likely that they did, for they sat apart from their elders, and no doubt observed their own manner of worship.

The Chapel soon proved inadequate for both Parish and College. It had caused no little friction in its two-fold use. A larger building was needed for commencement and other academic occasions, and the Church of Christ wanted a home it could call its own. John Wheelock therefore proposed that the Parish build a large meeting-house, promising that the College would pay for its use on special occasions. It was completed in two years at the cost of approximately $5,000, raised almost entirely by the sale of pews. The contracts specified that it should be built "according to the rules of good workmanship for a building of such kind including painting of the whole of the outside and so much of the inside as is usual to be painted in wellfinished meeting-houses."

It was dedicated on December 13, 1795. The present year therefore marks a double anniversary: the igoth of the first church building and the 175 th of the church organization. Its architectural glory was a tall slender spire, apparently similar to that of our new edifice and rising to the same height. It was to be ornamented with two balls: the lower made of wood "overlaid with gold leaf": the upper of "metal and gilt also." It threatened to collapse and was removed in 1827, leaving merely its square base, known as the "belcony."

In 1804 the Trustees of the College appointed Rev. Roswell Shurtlefi to the chair of divinity and assigned him the duty of pleaching to the students. The church, expecting that Professor Smith, who had been engaged as pastor on an annual basis, would now withdraw, as indeed he was perfectly willing to do, invited Mr. Shurtleff to become their minister. To their surprise, President John Wheelock, whose dominant trait was a passion to rule, refused to allow this and insisted that Professor Smith remain as pastor and that Professor Shurtleff be his assistant, for he feared that with anyone less subservient than Mr. Smith in the pastorate he could not control the actions of the church as he desired. The church members, however, asserted their independence and summoned a church meeting to vote on extending a call to Mr. Shurtleff. Then President Wheelock played his trump card.

In the early days of the church many settlers from across the river, in the section of Hartford then and now known as the Dothan district, had united with the church in Hanover, but with the passage of time, although retaining their membership here, they had ceased to attend meetings or contribute to the pastor's salary, and in 1799 had erected a meeting-house of their own in Dothan, and in 1800 had tried to settle a pastor there. They were for some reason or other completely at President Wheelock's command, and when the church meeting mentioned above assembled, to the astonishment of the village members, the Dothan contingent appeared in numbers sufficient, with John Wheelock and his two or three supporters in Hanover, to form a majority and to vote against the settlement of Professor Shurtleff. After efforts to effect a compromise had failed, a council which met on July a, 1805, sanctioned the separation of the Hanover members, twenty-two in number, into an independent church, Congregational in form, and connected with the Orange Association. It was named the Church of Christ in the Vicinity of Dartmouth College, in view of the fact that the Dothan congregation persisted in calling their meeting-house the Church of Christ at Dartmouth College.

President Wheelock refused to recognize the new organization and attempted to force the Trustees of the College to withdraw Mr. Shurtleff from preaching, thinking thereby to leave the church without a pastor. The Trustees refused, however, to be drawn into what they considered a local church squabble, with the result that they soon found themselves at open enmity with their President, who quickly carried his fight outside the limits of Hanover. The struggle between the President and the Trustees spread, first to the State Legislature, then to the Superior Court of New Hampshire, and finally, after Wheelock's death, to the Supreme Court of the United States, where Daniel Webster's eloquent plea saved from destruction the small college that he loved.

In the meantime, the church for a few years encountered grave difficulties, but under Mr. Shurtleff's able ministry soon emerged into a period of much prosperity. Only once more was it drawn onto the battlefield. In 1817 the University and the College were both functioning for the first time simultaneously, and each had appointed the same date for its commencement exercises. The College students, who far outnumbered those of the University, heard that the latter planned to be the first to arrive at the meeting-house for their ceremonies. Three days before commencement, therefore, the College students entered the church and barricaded themselves, with guards armed with stones and clubs at every window in the building and in the steeple, and held their ground for three days and nights. The University students wisely refrained from attacking so formidable and well entrenched an enemy, and on the morning of commencement meekly marched into the college chapel, of which the University held possession, and left the College to conduct its exercises peaceably in the meeting-house.

Professor Shurtleff resigned in 1826 because of ill health, but continued to live on in the village on the west side of the campus until his death in 1861, at the advanced age of 88, the last survivor of the active supporters of the College in the great controversy.

Mr. Shurtleff was succeeded both as professor of divinity and as pastor of the church by the Rev. George Howe. Frail health prevented him from preaching much of the time, and Presidents Tyler and Lord supplied the pulpit themselves for months on end, until in 1830 Mr. Howe resigned. The college was unable to fill the chair of divinity at that time, and at President Lord's instigation the whole relationship of church and college was changed by the formation of the Dartmouth Religious Society. Instead of the College furnishing preaching by its professor of divinity, with the church providing only the place of worship, the Religious Society, made up of townspeople and faculty alike, engaged a pastor independently, to whose salary the College contributed a substantial sum, recognizing him as the official preacher to the students. This arrangement continued, with slight modifications, for ninety years.

The first pastor of the church, as distinct from the College, was the Rev. Robert Page, who found the position too great a strain and who resigned because of ill health after a year and a half of service. The brevity of Mr. Page's stay and the peculiar nature of the congregation, composed of the diverse elements of citizens of the village, members of the faculty, and students, had gained for the church the reputation of a difficult one to satisfy, and almost two years passed before a minister could be found who was willing to accept the call. But in April, 1835, the Rev. Henry Wood began a turbulent but efEective pastorate.

Mr. Wood was plunged at once into a turmoil of social problems. The temperance movement was at its height, and the church adopted a resolution declaring the sale of ardent spirits to be a disciplinable offense. At the very next meeting it took action against a certain Mr. Tubbs, and after four months' probation suspended him from membership for persisting in the nefarious traffic. Then the anti-slavery movement burst with violence into the College, and Mr. Wood, who at first wrote an article against slavery highly pleasing to the undergraduates, later tried to follow a middle road and was roundly denounced by the students, who demanded his dismissal. In addition, he offended the faculty by advocating greater democracy in their homes, insisting that domestic servants should be treated as members of the family and given regular seats at the table. In 1840 he was dismissed, to the satisfaction of both himself and the church. But his ministry had been fruitful; additions to the church had been made at every communion but one during his stay—168 in all, and in 1838 the meeting-house had been remodeled without and within.

The improvements in the building included the addition of a somewhat inelegant belfry to the "belcony"; the placing of outside shutters on the windows; a division of the old square pews into "slips," but with the pew doors still retained; and a rearrangement of the pulpit and removal of the sounding board. And—profanation in the guise of progress—stoves were provided. Some eighteen years earlier a student had his feet frozen in church, but apparently no one had been in a hurry to prevent a recurrence of this inconvenience. Two stoves were placed at the south end of the room and two chimneys erected at the north end to draw heated smoke through long iron pipes running under the balconies. They dispensed odor as well as comfort and copiously shed creosote along the way.

With very little change in appearance this bleak and graceless interior served for two services each Sunday and for the major college events through the pastorates of Wood, Richards, and Leeds until the famed transformation planned by Stanford White in 1889. The effect of its unrelieved whitewash on the mind of a worshipper was unforgettably expressed by Mrs. Susan Brown, daughter of Pastor Shurtleff, and one not inclined to speak lightly of pastors. Said she: "When Dr. Leeds preaches, he looks like a fly in a pan of milk." Less subtly the students called it "the College barn." When the vestry to the west of the church was built in 1841, its cozy dependence worked at once on the student imagination; varying their earlier metaphor they now spoke of these houses of the Lord as "the cow and calf."

The Rev. John Richards was the next pastor, serving from 1840 until his death in 1859. Although an uninspiring preacher, he entered actively into the life of the community and won the affection of his flock. He was a quiet, scholarly man with an antiquarian bent, unconventional in manner, and often absent-minded. Once when reading a list of persons propounded for admission to the church, he said, "Kate Smith—comes from up the river, I suppose." At a meeting of the Northern Academy of Arts and Sciences he went sound asleep during the reading of a paper by a member of the faculty. His wife reprimanded him, whereupon he replied, "Humph! He sleeps when I preach."

On December 16, iB6O, Dr. Samuel P. Leeds commenced the longest pastorate in the history of the church, the farewell exercises upon his dismissal being held exactly forty years later to a day, December 16, 1900. He was then by vote of the Church elected pastor emeritus, and continued in that relationship until his death in 1910. Earnest, sincere, benign, he was a beloved figure in the community for half a century, even if the students did protest vocally from time to time against the boredom of his long and theologically heavily

weighted sermons. During his term of service 478 members were received into the church, almost exactly a quarter of whom were college students. He saw many changes take place, not only in the fabric of the meeting-house, but in the nature of the church exercises. During his early days there were, as there had been since the College was founded, two services each Sunday, forenoon and afternoon, at both of which full-length sermons were delivered. Student attendance was required by the College at both these services, as well as at morning and evening prayers in the chapel —four religious exercises in one day! But in 187 a the afternoon church service was given up, to the relief of both pastor and congregation, especially of the students. During the long Leeds pastorate the church building was several times transformed, the most notable changes occurring in 1889. The benevolent Hiram Hitchcock interested his friend Stanford White to design a new interior, which became celebrated as one of the most gracious places of worship in America. Mr. Hitchcock himself bore four-fifths of the expense of the renovation, and also donated Hanover's first full-toned pipe organ for the new alcove that had been built into the lengthened north end of the auditorium.

When the Stanford White remodeling of the meeting-house was made, the church voted to deny the senior class their timehonored privilege of using it for their Class Day exercises, concert, and debate. This caused hard feeling, and The Dartmouth commented with editorial bitterness,

"Thus new paint wins out over the custom of a century." It proved, however, to be only a temporary interruption of the use of the building as a main auditorium for the College. Besides having witnessed uncounted numbers of distinguished men receive honorary degrees at commencements, on its platform, the old church had been the spot where Ralph Waldo Emerson delivered his celebrated address to the Literary Societies in 1838; where Walt Whitman, shockingly garbed in flannel shirt, first read his noble poem, "As a Strong Bird on Pinions Free"; where Matthew Arnold mumbled what was said to be a profound lecture so low that only the front rows could hear him. The largest concourse of people who ever gathered there came on July 26, 1853, to hear Rufus Choate deliver his famous eulogy on Daniel Webster.

Dr. Leeds had long found his many duties an overtax upon his strength and in 1893 had offered his resignation, but instead of accepting it the church worked out an arrangement with the College by which Dr. Leeds would retain all the pastoral work but would preach only eight Sabbaths a year, the pulpit being filled for the remaining Sundays by a board of preachers, chosen and supported jointly by the College and the church.

In 1903 the College abandoned compulsory attendance at church services for the students. It was consequently felt necessary to obtain once more a settled minister, and in 1904 the Rev. Ambrose W. Vernon was called to the pastorate by the church and to the chair of divinity by the College.

Under Dr. Vernon was instituted the custom of receiving into associate membership students who were church members in their home communities, and for the first time in seventy years a change was made in the basis for church membership by a revision of the covenant. For the older formal covenant, which included articles of belief, was substituted the simple declaration of determination to be a disciple of Jesus Christ and to do the will of God as revealed through him.

Dr. Vernon resigned in 1907 to accept a professorship in the Yale Divinity School, and was succeeded by the Rev. Frank L. Janeway, who had come to Hanover the preceding year as associate pastor. His ministry covered five years. The year of his assumption of the pastorate was marked by the final separation of the College and the church in the joint use of the meetinghouse as an auditorium for all important public assemblies in our community. Webster Hall was completed in that year, was dedicated in October, and was used for commencement exercises for the first time the following spring. The Class of 1907 was thus the last of the 112 Dartmouth classes to receive their diplomas in the old White Church.

Mr. Janeway having resigned in 1912, the Rev. Robert C. Falconer, a vigorous young graduate of the College of the class of 1905, became pastor and remained likewise for five years. He had been trained under the newer movements in the theological seminaries, and his sermons reflected this training in their lessening attention to questions of dogma and their greater emphasis upon social problems. Perhaps the most lasting contribution of his pastorate was the revivification of the church school.

Mr. Falconer resigned his pastorate in 1917 to enter Y.M.C.A. work in France. The Rev. William W. Ranney, who came in November, 1917, began a ministry that promised to be most effective but that was cut short in two years' time by his death on February 2, 1920. Out of that brief pastorate, however, emerged two events that deserve mention. After years of increasing difficulty in raising sufficient funds for the support of the church, the Dartmouth Religious Society, which had been founded in 1830 for that purpose, was disbanded; the church was incorporated, and the conduct of its business affairs was transferred to a board of five trustees. The other event was the initiation, at Mrs. Ranney's suggestion and under her personal supervision, of the Christmas mystery, which, first presented in the old white church on the Sunday before Christmas, 1919, has become, as she predicted it would, a beautiful, worshipful, and service-giving adjunct to the holiday season in the community each year.

The Rev. Roy B. Chamberlin came to Hanover in 1921. His installation as pastor on November 7 of that year was the climax of a three-day celebration of the 150 th anniversary of the founding of the church, which had included an evening of reminiscences; a Sunday morning service at which Professor John King Lord had delivered an authoritative historical address; an afternoon service of addresses relating to the connection of the church and the College by the pastor, by President Hopkins, and by the Rev. Henry W. Hulbert, a descendant of Eleazar Wheelock; and an evening service for the dedication of the Runyon organ, a generous gift to the church by another Wheelock descendant.

On the material side Dr. Chamberlin's pastorate was marked by the completion of the parsonage, begun shortly before he arrived; on the spiritual side by a distinct broadening of the thinking and the activities of the church. During his term of service the church budget more than doubled in amount. Dr. Chamberlin was obliged because of illness to relinquish the pastorate in 1927, but his continued presence in Hanover as chapel director, fellow in religion, and professor of English in the College, has been a constant support to the church, the value of which is beyond estimation.

The pastorate of the Rev. William N. Spence began in 1927, to be terminated eleven years later after serious illness had incapacitated him for further active service. It is inevitable that memories of his pastorate should center in the profound changes that occurred in the church plant. On the evening of May 13, 1931, the old white meeting-house, which for 136 years had been the home of the church, the assembly hall of the college and the community, and an architectural landmark at the head of the college green, was totally consumed in the most tragically beautiful fire in the memory of any who stood on the campus that spring evening to watch helplessly as it burned. A mysterious flame in the lower northwest corner was discovered too late, for it had already climbed to the garret timbers from which it shot out in a mighty draft that enveloped the steeple, creating a grand pyre of flame.

For some years previously the plans for the future development of the College had contemplated an open lawn on the spot where the church stood, and after long negotiations an agreement had been reached between church and College by which it was proposed that the meetinghouse should be moved bodily from its site to that occupied by Rollins Chapel, where its colonial proportions would form a completing unit in the "old row" of Wentworth, Dartmouth, Thornton, and Reed Halls. But Providence intervened, and new arrangements had to be made. Finally, the church and the trustees of the College reached an amicable settlement, by which the lot on which the church had stood was transferred to the College in exchange for a sum which, with the insurance on the burned building, made possible the erection free of debt of the new meeting-house. The church was exceedingly fortunate in obtaining the services of the country's foremost church architect, Mr. Hobart Upjohn, and of Hanover's able contractor, Mr. Edgar Hunter, a combination that resulted in a very beautiful and serviceable building. The new church was dedicated with appropriate exercises on November 10, 1935.

With the coming of the present pastor, the Rev. Chester B. Fisk, in 1938, we move from periods of ancient history into one of current events. Mr. Fisk has won the admiration and affection of his parishioners as a most worthy successor in the long line of faithful ministers who have served the Church of Christ at Dartmouth College.

As once the old white meeting-house on the green held the affections of the generations now gone, so today the new house of worship has in one short decade won the loyalty of the parish, and in the years to come will gather to itself, as its predecessor had done, an ever-increasing body of tradition. How much more beautiful and useful it is than the old plant! Mr. Upjohn's architectural genius reproduced in its outward form a building of the Classic Revival period, reminiscent of the days when the church was young, yet perfectly adapted within to the needs of modern times. The auditorium possesses a quiet and peace, a toning down of color by the blending of white with soft blue and gray, a light without glare from windows that suggest the eighteenth century—all in harmony with our Puritan heritage, but completely relieved of the bleak severity that even Stanford White could not entirely remove from the earlier structure.

The diverse and complex activities that keep the parish house buzzing with life seven days in the week make the lectures and concerts of older times seem simple and monotonous. The fact that the meeting-house and the parish house are a single unit emphasizes a closer relation today between Sabbath worship and week-day living. The uses of the plant for community as well as for purely sectarian purposes, by such organizations as the Red Cross, Woman's Club, and Nursery School, mark this church as still a servant of the whole village.

With the moving of the church from its location on the campus to a spot a few rods farther north, it might have been expected that the bond implied in the latter part of the name of the church would loosen, but that has not happened. It is still the Church of Christ at Dartmouth College. It has been almost half a century since student attendance was- required at church services, but many a Sunday morning in term time now there are more voluntary student worshippers in the pews than Eleazar Wheelock ever saw. That little room in the rude structure on the corner of the campus where the church was gathered 175 years ago is but a memory dimmed by time almost to invisibility, but it is still a symbol —a symbol of a high purpose, of a noble beginning. The gleaming spire of the present church, set near the center of the college and the community, is also a symbola symbol of that same high purpose carried through the years to a considerable measure of fulfilment, but still a symbol not of an end, but of a beginning.

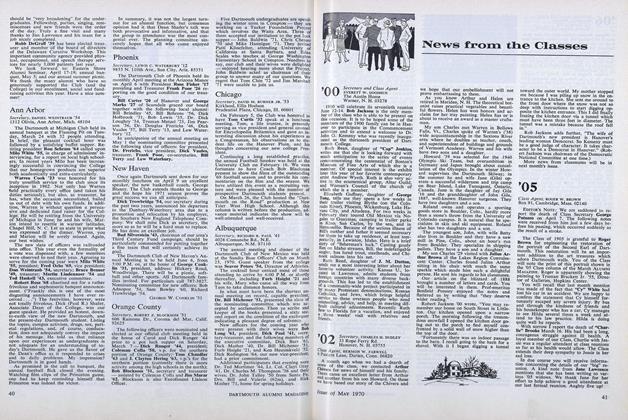

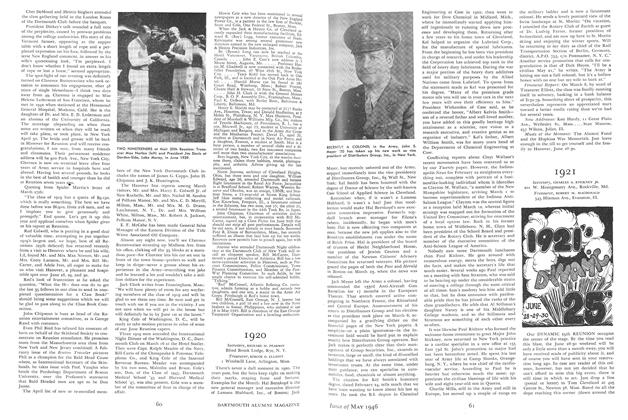

THE OLD CHURCH, VESTRY AND PARSONAGE formed a small cosmos at the north end of the Common. The Church, built in 1795, and the Vestry at the left, added in 1841, were known by early students as "the cow and the calf" and were destroyed by fire in 1931. The Parsonage (right), built in 1787, was moved in 1926 to its present site on North Main St. It was named Choate House after Rufus Choate, who there wooed and married the daughter of its owner, Mills Olcott of the Class of 1790, proprietor of the dam, locks, and mill at Wilder. The campus fence was removed in 1893.

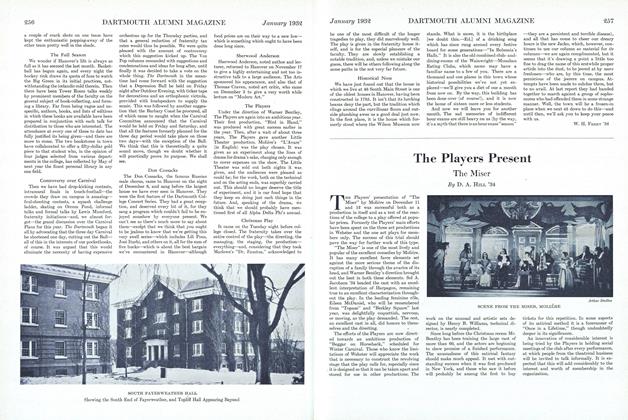

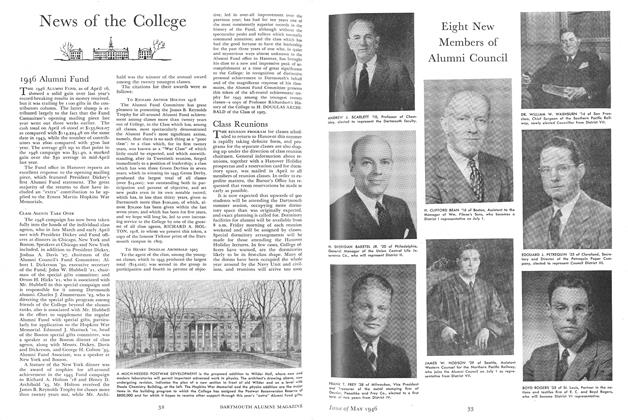

A RARE PICTURE OF A GREAT OCCASION, this shows the main exercises in the two-day celebration of the Webster Centennial in September 1901, as well as the classic design and decorations done by Stanford White, the famous architect, in 1889 when the church interior was remodeled. All important academic exercises were held here. Above, President Tucker is shown on the platform with Edward Everett Hale; Congressman Samuel McCail '74, orator of the day; and other celebrities including Governors, Justices,. Congressmen, and relatives of Webster. The pulpit desk, later rescued from the fire, now serves as the pulpit of the new White Church.

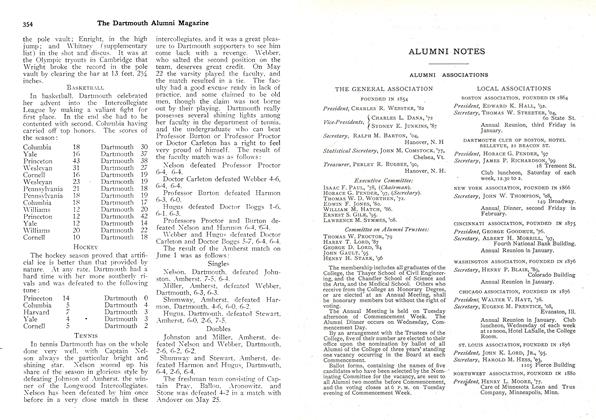

SAMUEL PENNIMAN LEEDS, D.D., nicknamed "Pa," had the longest pastorate in the annals of the White Church. Lasting from 1860 to 1900, it spanned the Lord, Smith and Tucker presidencies.

AFTER THE TOWER OF FLAME had reached the belfry and the historic church bell had fallen, there was a last spectral beauty to the fire which consumed the old church edifice on the evening of May 13, 1931.

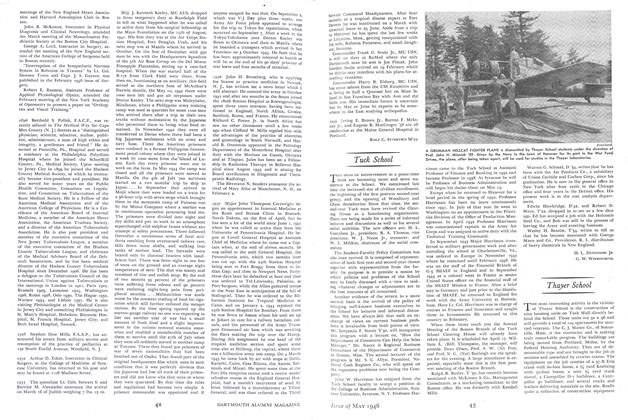

AT THE LAYING OF THE CORNERSTONE for the present Church of Christ, Dean Craven Laycock '96 holds the box containing historic church materials. Other program participants were the Rev. William H. Spence (center), then pastor, and Edgar H. Hunter 'Ol of Hanover (left), the builder.

On the evening of January 20, 1946, theChurch of Christ at Dartmouth Collegecelebrated the 175 th anniversary of itsfounding. The exercises, which were heldin the church building on College Street,consisted of a service of devotion, followedby a presentation by Professors Childs andWatson of a history of the church, illustrated by fifty lantern slides. The presentarticle is based on the manuscript of theiraddresses,, condensed to fit the space andinterests of the MAGAZINE.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Article

ArticleMedical School

May 1946 By Rolf C. Syvertsen M'22. -

Article

ArticleTwo Commonwealths: One World

May 1946 By THOMAS S. K. SCOTT-CRAIG -

Class Notes

Class Notes1918

May 1946 By ERNEST H. EARLEY, DONALD L. BARR -

Article

ArticleThe Role of the Humanities

May 1946 By ARTHUR M. WILSON -

Article

ArticleJESS B. HAWLEY '09

May 1946 By SIDNEY C. HAZELTON '09 -

Class Notes

Class NotesDartmouth Navy News

May 1946 By ARTHUR R. WILSON '47