BACK from Pacific and Atlantic, back from the wars which forced on them answers immediate and adult, the veteran-undergraduates have read about atom bombs and the atomic age and have been so much upset that they have put pressure on everyone for answers to questions.

"Are we close to the final catastrophe?" they ask. "Is Russia going to be able to wipe out New York, Chicago, San Francisco, Boston, New Orleans, and Los Angeles in the space of a single evening? Gan a nation small in size but unscrupulous defeat a big and peaceful nation? Are the 2500 bombs which the United States is said to possess going to be enough to secure us from the predatory?"

Though the atom bomb is also described as being one to revolutionize a peacetime world, the veteran-undergraduates fear its destructive influence so much that they talk little o£ a new power age in terms of convenience.

They want to know where the atom bomb fits in with a professor's thinking, with his philosophic and religious values.

Speaking for myself, I believe that the atomic bomb has been overpublicized, that it has not been seen in its true perspective. I see no reason why the atomibomb should not exist without danger in the midst of satisfied and great commonwealths.

The divergence of my point of view and many of those on the Dartmouth campus and elsewhere lies in the difference between our attitudes about physical diversity and human unity.

Let me begin by stating what I believe to be the unrealistic quality of much of the present-day thinking.

Many of my friends seem to be suffering from what I can only call an intellectual hangover. In common with most of the commentators, they talk in terms of a type of political diversity which to me seems so far on the way out as to be practically nonexistent. They speak of sovereign nation states, big and small, as if these still had a factual existence. "Russia" has a dispute with "Iran," which is brought in some sense before the United "Nations." Or "Britain" gets into difficulties with "Greece" and the "United States" with "Argentina." These statements seem to me unrealistic. The discussion of the present political problem—one world, two worlds, or none at all, as the phrases go—might be clarified if we distinguished between the real facts of physical diversity and the still more real fact of human unity. This I should like to attempt to do by associating our physical diversities with the phrase "Two Commonwealths" and our human unity with the phrase "One World."

I happen to hold it for a fact, daily becoming more visible, that basically no nation states exist today; and that, basically, there are no international relations. Human beings, on the contrary, are both grouping themselves and being grouped into Two Commonwealths, diverse and great; the Orient and the Occident; the Commonwealth of the Asiatic Heartland and the Commonwealth of the Atlantic Heartlake. For example, there is (as nobody will deny) a lot of badly needed oil in Persia-Iran. Its existence is not a national but a supranational problem, and is being handled as such. If we call it an "Iranian" problem, using the name that symbolized the attempt to turn the area info a westernized community, we think of the district as both a nation and as part of the Occident. Call it a "Persian" problem, and at once we see the relation to the days when the area was part of an Oriental "empire," itself a fraction of the ancient and ever youthful East. Till the question is really settled, the actual diversities involved might best be referred to as the problem of oil in Persia-Iran.

Or take the question of what for the moment I shall call "Hindustan." If one thinks of the problem in hangover terminology, then it appears as a dispute between "Britain" and "India," within the framework of the British Commonwealth of "Nations," with the emerging problem of national "Pakistan." But when Mr. Churchill referred to that area as the brightest jewel in the crown, he relegated it (intentionally or not) to an entirely new status; up till then it had been part of the state. And under the present British government the jewel will be pried loose and incorporated in a new and functional setting. Indeed, it is one of the unsought glories of Mr. Churchill that his gradually manifest destiny was in fact to preside over not only the liquidation of the British Empire, but even of the British Commonwealth of "Nations." I feel sure he really meant his offer to the French, of citizenship in a new commonwealth, and that offer led naturally to General Smuts' trial balloon concerning a new partial commonwealth on one side of the Atlantic Heartlake: Africa, Western Europe, the United Kingdom. Nor is it without significance how quietly the French dispossessed themselves of one to whom they owed so much, De Gaulle, a noble but antiquarian apostle of the "France" of Jeanne d'Arc.

The chaos of nation states is in fact giving way to the era of Great Commonwealths. With the gradual withdrawal of the British from "India" and of the United States Americans from "China," with the accomplishment of the partition of what was "Europe" and the return of many ethnic groups to the "East," the great SlavicSino-Hindu Commonwealth is being born in the Orient, in the Asiatic Heartland with its Rimlands. Similarly in the territories bordering the Atlantic Heartlakethe old "herring-pond" extended to the South Atlantic, with enormous consequences for the outnumbered AngloSaxons!—the former "nations" are organizing, shaking down, into a great Amerangl i an-Westeuropean-African Com m o nwealth. Hence the real pathos of Argentina, the real pathos of Spain. This, I hold, is the factual character of our diversity.

Several students and faculty have enquired whether I view the prospect of two emerging commonwealths with alarm. I must confess that I do not. I know of no large scale conflicts in which human beings have been engaged in which there were not (among other less admirable factors) real physical causes of war. But, as far as I can inform myself from such books as Spykman's Geography of the Peace or Rentier's Human Geography in the Air-Age both commonwealths will have adequate economic resources for their populations. I am assuming that today politico-economic factors far outweigh financial considerations; for even if, to some extent and in some quite mysterious fashion, the goldhoard in these United States is shipped about to various parts of the globe (and back again), few economists seem to believe that we face anything except managed currencies.

And even though Renner and to a slightly lesser extent Spykman write in a moral and religious vacuum, their information on the whereabouts of wheat and rice, coal and iron, oil and hydro-electric power, and above all of people, would seem to hold good. And if that is so, I can see no crisis arising out of physical diversity within the forseeable future. We can, of course, plan only for such a future. But in so far as we can rationally channel the currents of the time it would not seem too optimistic to plan for the next hundred years. After all, the much-maligned Congress of Vienna laid the foundations of the new Austro-Hungarian Empire; with it "our" Europe rose and with it "our" Europe fell, but that Europe spanned all of a hundred years, 1814-1914.

Passing now from the facts, the far from gloomy facts, of physical diversity, what of the bearing of the fact of human unity on the political problem? How far is that one world real?

There are some encouraging aspects of the situation. Bodies like the late League (of "nations") and the present Organization (of united "nations") do successfully deal with some problems on a human anworld scale. They can work towards certain improvements like a universal notation, or the social control of the traffic in narcotics or white slaves. They can perhaps be the clearing house through which stateless technicians can be exchanged between one commonwealth and another: engineers, linguists and the like. But there are some discouraging and limiting aspects of the situation, one being the notable absence of a world-speech. Orient and Occident will continue to speak to each other in translation, and the underlying (or better, overarching) human unity can be obscured. Are the teachings of the Gita or of the Gospels essentially parabolic, and if so, how does one interpret and apply them? In what sense do United States Americans mean to be good neighbors; do they act the good Samaritan to those who fall among thieves? In what sense is Stalin ruthless; Churchill, a war-monger? When Churchill lauds the English-speaking peoples, does one have to recall that he endorsed "Basic," endorsed British-American-Scientific-International-Commercial?

The chief reality is, however, the moral, intellectual, and religious unity which binds East and West. All the great philosophies, all the high religions, together ereate one world. They are unanimous in showing that the talking-cooking-laughing animal called man is, at all times and in all places, recognizably neither an ape nor an angel but himself. Unanimous, too, of course, that man, though remaining himself, is always in a very parlous condition from which he requires emancipation. Unanimous that, and here I use Occidental terms, man's pride (the Prometheus, the Faust, the Adam in all of us) has already created such fission in the spiritual universe that his destruction of the physical universe would or will come as an anti-climax. Unanimous that biological extinction in a manner more or less painful, more or less protracted, awaits in any case everyone that is or will be alive. Such is man, everywhere, always; a rational animal that can be counted on to try to act like a god and to fall so much lower than the beasts; but still human and not a devil. Any planning, therefore, for a just and durable peace must in great measure mean avoidance of injustice and of as many forms and instances of conflict as possible. Yet, the common recognition of our privilege and our plight, however inarticulate we may be, even if we can only sputter through our vodka "Well I'll be a.. ..," is enough to ensure that our human world will endure at least another hundred years, especially when the economic political facts are what they are.

I hope that the overpublicized atomic bomb can now be seen in what I would regard as its true perspective. All I would. care to add can be put in an anology. We are, in my view, very much in the situation of intelligent and informed Western people in the fourteenth and fifteenth centuries. By the end of that period, it seemed as if the institution of plate-armor had rendered the knight invincible, and clamped on men (in the, to them, known civilized world) the shackles of baronial feudalism and separation. But the knight, that human armadillo, was actually imprisoned in the useless perfection of his armor. Already that scientific monarch Edward 111 of England had abolished the chivalric conventions of feudal warfare and ended the stalemate of the Hundred Years' War. And already the bubo, that dread microbe of the Black Death, had undermined the economic and political institutions of the age. The nation states were aborning; the signs of the times could be read; therefore. the dreadful gunpowder was perfected. So yesterday we built the Maginot Line (the French are part of us, and so of course, are the Germans) in all its plated uselessness; we seemed to have imprisoned men on either side of its great but insufficient length, and to have clamped on them forever the divisions of the nation states. But already the scientific Germans and Japanese were abolishing the far from chivalric codes of recent "declared" warfare. Already our fumbling methods of chemicotheraphy (not to speak of artificial conception-control) had upset the health and population ratios and undermined the economic and political institutions of the times. The commonwealths were coming to birth; and we proceeded to the perfecting of the atomic bomb, the Germans at first with more success than ourselves, though with final frustration on the part of our recent enemies. Gunpowder ended the middle ages; the atomic bomb ended "postmedieval" times.

But despite the munitions makers, gunpowder did not get out of hand in thpost-medieval period whenever politicaleconomic conditions were relatively satisfactory, as in the Europe of 1814-1914. And despite the continued manufacture of the bomb I see no reason why it should not exist innocuously in the coming century of the great, satisfied commonwealths.

I hope also that some equally overpublicized religious irritations can now be seen in a healthy perspective. I would not for a moment deny that the fact of humanunity in and between East and West cannot obscure the real though not dangerous supra-human diversity. I doubt very much whether Protestants, Catholics and Jews mean the same thing by Heaven as their destination, and I think any of them if they arrived at the state of Nirvana would, if still conscious, evince considerable surprise and alarm. But we are concerned only with what the high religions have

and do in common, their emphasis on the dignity of man and their rebuke to the pride and sentimentality in men; we are concerned only with the safeguards they provide for sanity and justice and peace. It is a quite unforeseeable future in which any of our secular cultures will be amenable to the missionary discipline of the supra-human elements of the great faiths. And I find it hard to credit, for example, that the atheistic Stalin really fears a Christian crusade, or that any significant representative of the Latin Church is religiously frightened by atheistic Communism. That would be to set too high a premium on human ignorance and stupidity.

To return to my main topic, the general philosophic and religious significance of the pattern of emerging commonwealths in the coming century and the place of the atomic bomb in that setting. The issue has been very clearly mis-stated by the writer of the "Topics of the Times" (011 April 1; could he have been fooling?). Without reference to the major economic and political considerations, he wrote that, since the invention of the bomb, the physical scientis"takes his place now beside the philosopher, the artist, the teacher, the man of God." But surely the physical scientist must still listen to the independent findings of his colleagues in the social sciences. And although we in the great commonwealths must all become more scientific, surely the scientist in us must recognize above all the fresh relevance of that one world of ancient truth which only those possessed of humane and religious insight have any special authority to proclaim. As the issue has been stated as clearly as possible in a recent Harper's, by Mr. Stimson, the ex-Secretary of War:

The focus of the problem does not liein the atom: it resides in the hearts of men.

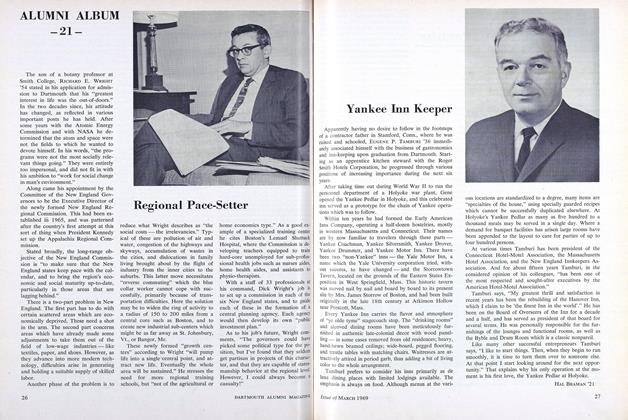

SCIENTIST ON THE JOB. Dr. John Turkevich '28, Associate Professor of Chemistry at Princeton, shown in the University's Frick Chemistry Laboratories, where he was engaged with others in special atomicenergy research which the War Department hailed as helpful to the success of the Manhattan Project.

Owner of the longest name on the faculty, Thomas Stevenson Kirkpatrick Scott-Craig has been Assistant Professor of Philosophy at Dartmouth since November 1944. He teaches a freshman philosophy course on "The Modern Mind and Its Heritage" and also conducts a seminar in religion. Dr. Scott-Craig was at Hobart College for six years, 1938 to 1944, as Assistant Professor of English and Lecturer on Christianity and' Western Civilization. While there he directed a three-year coordinated program in the humanities and married Mary Ellen McCormick, Dean of William Smith College and Professor of Education. Born in Edinburgh, Scotland, Dr. Scott-Craig received his M.A., B.D. and Ph.D. degrees at Edinburgh University. He came to this country in 1935 as Visiting Professor at Drew University and then became Guest Assistant at General Theological Seminary in 1937, before going to Hobart. He is the author of Christian Attitudes to Warand Peace (1938) and of many articles. Professor Scott-Craig, called to Scotland last summer by the death of his father, overcame the difficulty of getting passage back to America in the fall by swabbing decks and sorting linen on a Liberty ship. It took a while for the crew to get over the idea that he was some sort of spy.

ASST. PROFESSOR OF PHILOSOPHY

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Article

ArticleTHE WHITE CHURCH

May 1946 By PROFS. FRANCIS LANE CHILDS '06 and ERNEST BRAD LEE WATSON '02 -

Article

ArticleMedical School

May 1946 By Rolf C. Syvertsen M'22. -

Class Notes

Class Notes1918

May 1946 By ERNEST H. EARLEY, DONALD L. BARR -

Article

ArticleThe Role of the Humanities

May 1946 By ARTHUR M. WILSON -

Article

ArticleJESS B. HAWLEY '09

May 1946 By SIDNEY C. HAZELTON '09 -

Class Notes

Class NotesDartmouth Navy News

May 1946 By ARTHUR R. WILSON '47