BEFORE one can comprehend with any clarity our Inter-American relations he must completely disassociate the concept that Latin-America is a political entity in itself. There are twenty LatinAmerican nations, all sovereign republics, varying considerably in cultural as well as economic background. Although Spanish is the language most widely spoken, Portuguese is the language of Brazil, where one-third of the hemisphere's population dwells, and French is the language of Haiti. Over the years this has tended to preserve cultural and economic ties with Europe rather than the United States. However, native Indian culture has had a lasting influence on the mores of many countries; for lndian dialects are used more than the Romance languages in Bolivia and Paraguay.

Great extremes of climate—even within small countries—tend to divide the political and social economy of many of these republics not only from one another but also within themselves. Anyone who has walked along the hot docks of tropical Guayaquil and then zoomed over the Andes to cool Quito in its quaint setting 9500 feet above sea level, largely untouched since the Spanish colonial period, will better understand the politics of Ecuador. Or if one has felt the tempo of Sao Paolo—the Detroit of South America—moved on to beautiful Rio de Janeiro with its lavish beaches and striking modern architecture, he feels he has been in two different countries; and when he takes the long hop from Rio to Belem, flying over the lush green wastelands .of the Amazon, it is hard to realize that all these different impressions are part of one vast country—Brazil.

There are great extremes of wealth and poverty. While literacy is high in countries like Argentina and Uruguay, it is almost unbelievably low in Bolivia, and in most countries it is not comparable with our own.

Add to these things the fact that at the beginning of World War II there were but 55,000 citizens of the United States in all of Latin America as against several million of Italian and German descent and that all of these twenty proud and cultured peoples had constantly been warned against "The Colossus of the North."

Then one can well ask why all these nations, except one, chose to support the Allied cause in World War 11. What brought it about and what must we do now to continue and expand the hemisphere understanding and solidarity which reached such a high point during 1940-1945?

In the past, most of our schools touched but lightly upon Latin-American history. The first, and too often their last, study of our neighbors to the South dealt with the Monroe Doctrine—although this is where United States hemisphere foreign policy may be said to have begun.

In 1823 our infant republic had gone through a difficult half century trial and error period of Democracy and the LatinAmerican countries were just then becoming emancipated from European domination—notably that of Spain. So our young nation was interested in and sympathetic with these struggles.

In addition to the Monroe Doctrine there are two important general factors which should be borne in mind— (1) All of the Latin-American countries were a quarter to a half a century behind the United States in securing their freedom from Europe. Their people were treated as slaves and their wealth was exploited solely to satisfy the greed of the mother country. On the other hand, the people of the United States were settlers from other lands who had searched for and fought for liberty. This gave the United States many advantages in the development of selfgovernment that its neighbors to the south did not have in this New World political experiment, (2) The development of our Latin-American foreign policy was the work of both our two major political parties. In the post-Civil War period, Secretary of State Blaine, a Republican, was the first to call a successful inter-American conference. On the other hand, another Republican, Theodore Roosevelt, by his tacit aid in the secession of Panama from Colombia, gave credence to the belief that the United States had imperialistic aims in Latin-America. The so-called period of "dollar diplomacy" came into its own after this, culminating in our intervention in Haiti, the Dominican Republic, Nicaragua, Cuba and Mexico. Security was the motivation and perhaps the subsequent military value of the Panama Canal can now justify the ends Theodore Roosevelt sought, if not the means.

Although President Wilson always believed himself to be a non-interventionist, his handling of the Mexican situation before and during World War I left much bitterness and charges of intervention. President Hoover made some moves to rectify past mistakes in our Latin-American policy in the Carribean area, but it was President Franklin Roosevelt who gave the hemisphere the "Good Neighbor" policy of today.

Franklin D. Roosevelt was not only "simpatico", but he also very realistically implemented his understanding of LatinAmerica with a program of action., particularly through the good offices of three unusual men.

Secretary of State Hull set the tone for better inter-American relations and made tangible steps in this direction through his reciprocal trade treaties. Sumner Welles, with years of experience in this area of the world, supplemented the work of Mr. Hull with his diplomatic ability in many conferences, particularly at Buenos Aires (1936) and Rio de Janeiro (1942), where new patterns of international relationship were established. With the appointment of Nelson A. Rockefeller as Coordinator of Inter-American Affairs in 1940, the government had a man of action who not only implemented our foreign policy with the peoples of the other American republics, but whose energy and resourcefulness helped block subversive Axis propaganda and economic influence at a most critical time in our history.

Probably the greatest step forward in inter-American relations during the latter part of Franklin Roosevelt's administration was the almost complete acceptance by the other American Republics of our sincerity in advancing the "Good Neighbor" policy—concretely illustrated by our adherence to the doctrine of non-intervention as finally adopted at the Buenos Aires Conference in 1936 declaring inadmissible the intervention of any of the American Republics in the internal or external affairs of one another. This move was further enhanced by the Act of Chapultepec at Mexico City in 1945 when the American nations pledged themselves to act together against any threats against any American state from any source. The recent proposal by President Truman for an "Inter-American Military Cooperation Act", in furtherance of the Act of Chapultepec and the Charter of the United Nations, is one more step toward full realization of the principles of consultation and joint action.

The story of our Argentine relations by itself is a long case study in United States foreign policy. But here a few brief statements must suffice at the usual risk of omission and over-simplification.

United States relations with Argentina have been difficult and uneven for many years but especially since World War II broke out in Europe. Our sanitary code against Argentine beef has been only one of a series of irritants.

Argentina is the country in South America most like the United States in climate, standard of living, and the fact that it has been built up by immigration from the Old World. Buenos Aires is a charming cosmopolitan city of three million people, about one-fourth of the entire population of the country. The chief exports of the country are wheat and beef. Great Britain is its best customer. British interests control its railroads and some other utilities. Her cultural ties are European and especially French. Its great leader, Jos6 de San Martin, gave the country its independence early, but it was not until 1862 that it had its first constitutional President. In 1943 a coup put a military government in power,—a power which has been reaffirmed in the recent election of Colonel Juan Peron, the "strong man" of Argentina.

At the beginning of the War, Argentina gave "non-belligerent" status to the United Nations, which accorded privileges in the use of ports and waters denied the enemy, and continued to ship food to the Allies, but not until after the Mexico City Conference in 1945 did it declare war on the Axis.

Argentina's fulfillment of her commitments under the Act of Chapultepec and the United Nations Charter has been constantly in question. All of the other American republics, including the United States, have given Argentina every opportunity to return to her rightful place in the community of nations.

In the recent election, the liberal and democratic coalition led by Tamborini made a good popular showing, considering the five years of "state of siege" and political persecution, but could not stem the nationalistic peronista tide. So once more Argentina is the Latin American dilemma.

Our Latin American Policy must have as its continuous objective social and economic progress and a higher standard of living for all the peoples of the hemisphere. This can be the only sound way to insure the growth of free, democratic governments. It can and must be achieved by tangible implementation of the Good Neighbor Policy. From the point of view of the United States this is only enlightened self-interest. Not until the standard of living of the 133,000,000 people of Central and South America is raised can they produce the maximum quantity of goods, largely non-competitive, for exchange for manufactured goods from the United States.

We must continue to exchange technicians and missions in the fields of medicine, sanitation, agriculture, and all others that are mutually desirable—including the military. We must also continue the trend of north-south flow of cultural understanding. We should not try to make Latin Americans like ourselves or vice versa, but we should know each other's problems and appreciate each other's difficulties. Travel needs encouragement and the exchange of scholars should not flag. We have much to learn from the centuries-old universities of our neighbors and they can benefit much from a better knowledge of our educational system and our technological society. Reciprocal trade treaties should be extended and enlarged in scope. Latin America has nearly four billion dollars looking for farm machinery, transportation equipment and other products of our industrial economy. It is to be hoped that our exporters will see to it that some percentage of the goods soon to flow into our consumer market will be earmarked for Latin America, if we expect to compete with other nations as in the past.

Economic development should be encouraged. In raw materials Latin America is rich. She needs our "know how", and some capital. New development enterprises should be on a mutually financed basis and the Latin American countries should be shown that it is to their advantage to remove some present restrictions and that they should guarantee greater security of investments on this cooperative venture basis.

During the dark early days of the War, and especially after the fall of the Far East, our critical and strategic materials came largely from our Central and South American allies. This increased diversion during the war years left these nations with economic and social disturbances as great as our own and it is our duty to help them stabilize their post-war markets and readjust economically so that the burdens of unemployment and inflation will not prove disastrous.

Joint consultation on all matters relating to the security and well-being of the hemisphere should continue to be a touchstone of the Good Neighbor Policy.

Politically we must further the solidarity and human progress of the hemisphere to a point where the nations of the New World will stand as proof to the rest of the world that the Atlantic Charter is not another scrap of paper to be enshrined in a museum. Rather that here is a symbol of what the Charter means—an unparalleled achievement of free peoples in this, our generation, the first of the Atomic Age.

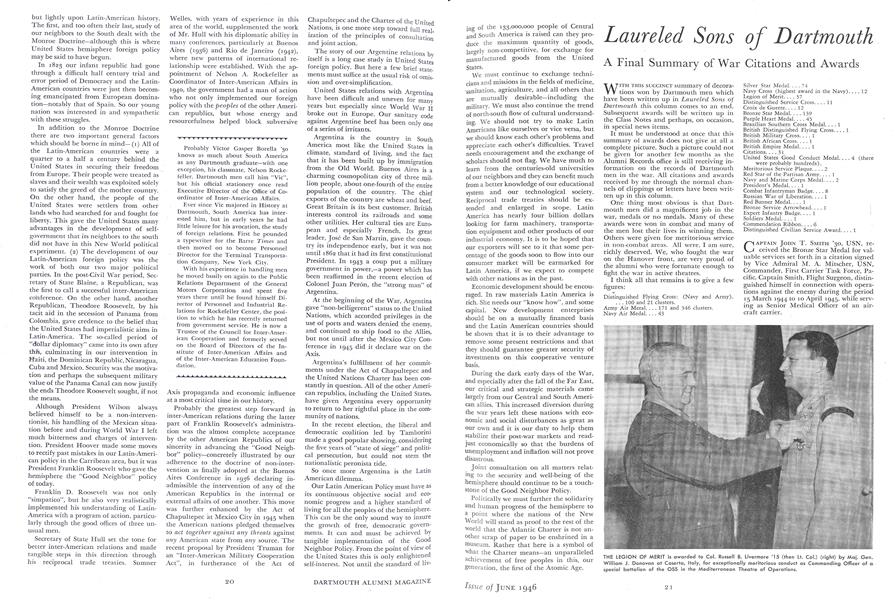

VICTOR BORELLA '30, who writes of Latin America, shown arriving by plane at San Jose, Costa Rica, in June 1945, when he was making an extended trip among our neighbors to the south.

Probably Victor Gasper Borella '30 knows as much about South America as any Dartmouth graduate—with one exception, his classmate, Nelson Rockefeller. Dartmouth men call him "Vic", but his official stationery once read Executive Director of the Office of Coordinator of Inter-American Affairs. Ever since Vic majored in History at Dartmouth, South America has interested him, but in early years he had little leisure for his avocation, the study of foreign relations. First he pounded a typewriter for the Barre Times and then moved on to become Personnel Director for the Terminal Transportation Company, New York City.' With his experience in handling men he moved busily on again to the Public Relations Department of the General Motors Corporation and spent five years there until he found himself Director of Personnel and Industrial Relations for Rockefeller Center, the position to which he has recently returned from government service. He is now a Trustee of the Council for Inter-American Cooperation and formerly served on the Board of Directors of the Institute of Inter-American Affairs and of the Inter-American Education Foundation.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Class Notes

Class Notes1918

June 1946 By ERNEST H. EARLEY, DONALD L. BARR -

Article

ArticleThe Show Went On In Spite of Wartime Setbacks

June 1946 By HENRY WILLIAMS, -

Article

ArticleUnited States Foreign Policy and Europe

June 1946 By JOHN C. ADAMS, -

Article

ArticleA Hard Job of Education A Hard Job of Education

June 1946 By JOHN W. FINCH -

Article

ArticleThe Truth About China

June 1946 By WING-TSIT CHAN, -

Article

ArticleRussia and the United States

June 1946 By OLIVER J. FREDERIKSEN '16