As OF TODAY there is a staggering list of points of conflict between ourselves and Soviet Russia. There is the deadlock over the government of Germany; Russia's refusal to accept joint withdrawal of occupation troops from Austria; Russian insistence upon control of the Dardanelles, bases in the Dodecanese Islands, and sole trusteeship over Tripolitania; Russia's backing of Yugoslavia and ours of Italy in claims to Trieste; American and Russian sympathy for opposite sides in the Chinese civil war; the installation of Communist regimes in Poland and the Balkans; the split occupation and Russian stripping of Korea; Russia's insistence upon the overthrow, at the cost of civil war if necessary, of Franco's regime in Spain; pernicious meddling through Communist Party leaders and Soviet spy rings in the internal affairs of ourselves and our friends; the boycotting of United Nations decisions by Russia when her proposals are overridden; provocative announcements in the Soviet press and by Soviet authorities of an intention to press forward to a vast re-armament program. When protests are forthcoming, Russia complains that her intentions are purely peaceful and insists that she is misunderstood. But she clamps down across Eastern Europe a rigid barrier of censorship behind which no foreign observers can penetrate to learn the facts upon which an understanding could be based.

What, one is inclined to say, can America do but accept the challenge and make full use of her financial resources and her armed might to align herself with other powers which find Russia's intransigeance intolerable, and settle matters once and for all.

Fortunately for the peace of the world, Russia represents a combination of material and moral forces too powerful for so shortsighted a solution. She has a population of two hundred million in the Soviet Union alone, and controls an additional one hundred million in the border states of Eastern Europe under Soviet tutelage. Beyond she holds the allegiance of many devoted, if sometimes bewildered, Communist Party members and their left-wing sympathizers in every country in the world. She can count upon strong support among the colonial natives of the Western empires, to whom a fresh outbreak wouM be a new indication of the madness of the Western world. Economically, Russia has an immense advantage in her centralized direction of resources and management and men and machines.

One of the most significant additions to Soviet Russia's strength has resulted from the abolition of national distinctions in cultural and political life. By her acknowledgment of the equality of the Ukrainians and White Russians and Tartars and the rest of the more than one hundred and fifty nationalities which make up the Soviet Union, Russia has won the support of millions of non-Russians. She has turned a liability into an asset, and by educating her minorities and offering them opportunities for advancement to positions of responsibility she has added immensely to the human resources of the Soviet Union. In the border states, while she has made many enemies, she has also won many friends by her sponsorship of a long overdue economic and social revolution.

There are, of course, serious weaknesses in Russia's position. While she has the advantage of a centralized direction over her great resources and population and over those of her neighbors, there is in backward Russia with its millions just emerging from illiteracy and with its lack of democratic checks an astounding amount of waste and inefficiency, both at the top and at the bottom. What she gains in flexibility in over-all planning is largely lost in the fear of responsibility and the discouragement of experimentation on the part of the individual. The absence of strikes and the avoidance of unemployment are to a great extent offset by the periodic draining off of Russia's most energetic and independent-minded citizens into labor camps or worse. And finally, as far as the puppet states are concerned, it was one thing to channel in Russia's favor the pent-up dissatisfactions of national minorities, depressed peasants, and sufferers from religious obscurantism and intolerance. Now that the revolution has been accomplished, the task of cashing in on the gratitude of the fiercely nationalist and perennially turbulent Poles and their Balkan neighbors may well be beyond Russia's ability. And in the outside world, Russia's attempt to overplay her hand in the game of power politics has undoubtedly strengthened the effort of the United States to call a halt.

On balance, it is certainly true that Russia is far behind the United States in the productive power and the international goodwill which are the determining factors in the play of modern world politics. But Russia is too strong to be simply disregarded.

If we cannot simply disregard or override Russia, what can we do? Certainly it is not in the American tradition for us to sit back and wring our hands while we blame others for our troubles and wait for someone else to provide a solution.

In the first place, we can keep our heads. Russian-American relations are by no means in as hopeless a state as some commentators would seem to believe. The vacuum between the American, British, and Russian spheres of influence has by now become pretty well filled, and it was chiefly the existence of this vacuum which led to the alarming expansion of Russia's area of domination. It seems obvious that Russia will not let herself be driven by financial pressure or military threat behind the line which she now holds, and it is equally obvious that we will not permit her to advance beyond the line which we have set up. There will be stubborn jockeying for the last inch, in Trieste and in Manchuria, in the Dardanelles and in Tripolitania, but neither side can or will permit these minor issues to be settled otherwise than on a basis of compromise. Both the United States and Russia will in the end stand firmly behind the United Nations, for both have incomparably more to gain by the maintenance of the status quo than by a serious struggle over what are now matters of comparative unimportance. Our chief concern here is to make clear exactly where we stand, and to make it clear also, both to ourselves and to Russia, that we are more interested in a stable peace than in monopolizing world power.

We can also make greater efforts than we have made in the past to understand what it is that Russia wants. Any action on our part that fails to take into account what Russia feels to be her needs will be vigorously, and rightly, resisted by Russia. Stalin has said that Russia will accept no decisions in which her point of view has not had consideration. It is no more than what we ourselves have said.

What is it that Russia wants? Whatever her long-range views, Russia wants for the present exactly what we want—security. She wants and needs it much more desperately than we do because she has suffered infinitely more human and material loss from world insecurity than we have. Even for her ultimate aim of world Communism she needs a period of peace, for another world war would surely mean the collapse of Russia, and an end to the experiment of "Communism in one state."

If we expect Russia to rest her future in the United Nations, we too must be willing to take the gamble. If we insist upon playing a lone hand in the Pacific, we can hardly demand of Russia that she abandon power politics and entrust the fate of her people to the mercy of the world. We, it should be remembered, insisted no less firmly than Russia upon the right of a great power veto. Or if we make use of our financial power purely as a means of expanding American markets regardless of the effect upon other economies, or as a political weapon to impose upon weaker states our particular brand of political and economic life, we cannot expect Russia to refrain from drawing what advantage she can from our shortsightedness.

International relations should be far more than mere diplomatic jockeying for position. American policy toward Russia should cease to be chiefly negative and should "accentuate the positive." It should include a strong program for cultural and economic exchange. We are proud to know that there is much that Russia can learn from us in the field of industrial production, and in the areas of political democracy and respect for the individual. Here, particularly in so far as political democracy is concerned, we could increase Russia's appreciation if we could improve the working of our own model. We could also add to the attractiveness of our economic system by showing that it can work in peace time as well as in war. But it is not Russia alone that has much to learn. We in America can take lessons from Russia in the value of a coordinated and cooperative approach to the problems of national economy. I know no sadder commentary upon American intelligence than the belief that national planning is impractical just because in Russia it was imposed from above by force. Among other lessons which we can learn from Russia is that of equal opportunity for women. Russia can also teach us how to profit by using the human resources now going to waste through our failure to educate and give stimulating economic opportunity to our negro and other depressed groups.

An exchange of goods and services between Russia and the United States could be highly profitable to both. In fact, the most important single factor in getting Russian-American relations on a satisfactory basis for the next few years would be to get America herself into production. But when we do develop business contacts with Russia they cannot be made conditional upon Russian acceptance of political or social terms or used as weapons in power politics.

In looking to closer cultural, economic, and political relations with Russia, we will need many more persons acquainted with the Russian language and with Russian life and traditions than are now available. There should be a great expansion of courses on Russia and her language in our universities. Russian is now taught in nearly one hundred institutions of higher learning in the United States, but the total number of students is still comparatively small. Russian should also be taught in our high schools at least to the same extent as French and German. Only then will it reach the degree of popularity it deserves in our colleges.

For the longer view, the solution of Russian-American conflict depends upon a radical revision of people's thinking—upon the abandonment of dependence upon individual or group or even national selfsufficiency and the frank acceptance of the fact of world interdependence. There is, to be exact, no such thing as a problem in Russian-American relations. There is only a Russian-American phase of a problem in world anarchy. The root cause of our troubles is our futile efforts to live disconnected and isolated lives in a shrunken world. Such problems as the rise of pressure groups at home, and the emergence on a worldwide scale of international Communism and cartels and alliances and spheres of influence are half-conscious efforts to seek order in the midst of chaos. It is not necessary to point out that in this as in all else the solution is not one which we can bring about by ourselves. We are as dependent upon the rest of the world in finding a solution as we now are in sharing the strains before the solution is found.

I should like to add a few suggestions as to the role of Dartmouth. Through the system of selective admissions Dartmouth has broadened out from a New Hampshire college to a college for the whole nation. Why not for the world? As it becomes possible I should hope to see many Russian and other Eastern European students brought to Dartmouth, through exchange fellowships and otherwise. And Dartmouth undergraduates should go out in increasing numbers for a year abroad or in service apprenticeships to United Nations organizations. The GI Bill of Rights offers veterans the opportunity of taking courses in approved foreign institutions on the same basis as in the United States.

Dartmouth pioneered in the field of Russian studies with the courses taught a generation ago by Mrs. Isabel Hapgood and is still in the forefront with those given by Professor von Mohrenschildt. But is the number of students encouraged to study Russian culture and the Russian language commensurate with the importance of Russia to America?

Is full use being made of Dartmouth's magnificent library? It would destroy Dartmouth's character to make of the college a graduate institution, but the Library is too good for undergraduate work alone. The Hanover Holiday is a fine extension of the use of Dartmouth facilities. And so is the informal gathering of professors and students from other colleges who spend their summers in Hanover browsing in the Baker Library. Could not a more definite effort be made to encourage the use of the Library through some kind of international summer institute?

EXPERT ON RUSSIA, Prof. Oliver J. Frederiksen '16 of Miami University, Oxford, Ohio, served for two years with the OSS during the war.

PROFESSOR OF HISTORY, MIAMI UNIV.

Professor Oliver Jul Frederiksen '16 was the principal expert on Baltic, Ukranian, and Polish affairs in the Foreign Nationalities Branch of OSS, Washington, from 1943 to 1945. He is now back in Oxford, Ohio, in the Department of History, Miami University. Mr. Frederiksen, a true cosmopolite, learned Russian in 1921, went to Honolulu for a year's training in the Y. M. C. A. administration where he worked with Chinese, Japanese, and Korean leaders. Then for three years, he lived in the Ukraine during the famine and grew to know well Moscow and Leningrad. From 1925 to 1932 he spent time in Estonia, Latvia, and Greece. To balance his diet he returned to the United States to study at Cornell and Columbia, and win a Ph.D. Also a cosmopolite, Mrs. Frederiksen, n£e Schwanfeldt, had an English mother, a German father; she was born in Russia, educated in Holland; she was a citizen of Latvia and married her husband in Riga; two of the Frederiksen children were born in Vienna.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Class Notes

Class Notes1918

June 1946 By ERNEST H. EARLEY, DONALD L. BARR -

Article

ArticleThe Show Went On In Spite of Wartime Setbacks

June 1946 By HENRY WILLIAMS, -

Article

ArticleUnited States Foreign Policy and Europe

June 1946 By JOHN C. ADAMS, -

Article

ArticleA Hard Job of Education A Hard Job of Education

June 1946 By JOHN W. FINCH -

Article

ArticleThe Truth About China

June 1946 By WING-TSIT CHAN, -

Article

ArticleOur Latin-American Foreign Policy

June 1946 By VICTOR G. BORELLA '30

Article

-

Article

ArticleOne-Finder Melody Is "Pops" Hit

October 1951 -

Article

ArticleNATIONAL AWARD

OCTOBER 1964 -

Article

ArticleThe ice rink cometh

JANUARY/FEBRUARY • 1987 -

Article

ArticleMessage from the South

JUNE 1977 By ANNIE L. MORGAN -

Article

ArticleTHE LIFE AND LETTERS OF NATHAN SMITH, M.B., M.D.

November, 1914 By Emily A. Smith, C.C.S. -

Article

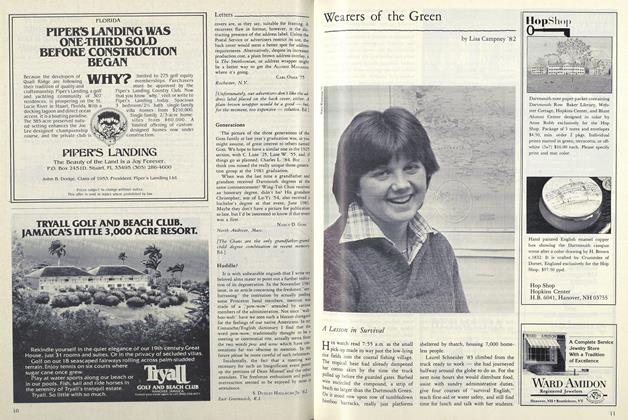

ArticleA Lesson in Survival

JAN.- FEB. 1982 By Lisa Campney '82