THE United States has made definite commitments in China from which she cannot withdraw. Right now, American officers are reorganizing and equipping the Chinese army. American factories are training Chinese industrial personnel. The Bureau of Reclamation is completing plans for the huge Yangtze dam. And General George Marshall is personally mediating the Chinese civil war. At the same time, Chinese national life is unmistakably being geared to the American pattern. Already the Chinese educational system is American. The new constitution now being drafted approximates the American constitution more than any other. Most important of all, the majority of China's political, intellectual, and educational leaders were trained in American institutions, and therefore have American ideals. Thousands of Chinese science students are being educated in American universities while American officers are training Chinese army and naval personnel. In the immediate future, Chinese industrial and military leadership will be American too.

All these facts indicate that Sino-American relations in the future will be entirely different from the past. They are already different now. Hitherto it was chiefly a relationship in trade. The United States was to China primarily a source of overseas remittance and China to the United States was hardly more than a market, and not an important one at that. Now the new relationship is one of mutual assistance. China needs American aid in her international position, political reconstruction, and economic reform. Similarly, the United States needs China to check Japanese aggression, to absorb American products, and to buffer between her and Russia. Furthermore, our former relationship was one of inequality, characterized by kowtow, extraterritoriality, and the Exclusion Act. Today the new relationship is one of equality, with all these stupidities gone and forgotten. Most important of all, the new relationship is a relationship of partnership in building peace.

On the basis of this new relationship, the United States Government has officially declared for a strong and united China with a coalition government and a nationalized army under the leadership of Generalissimo Chiang Kai-shek. To me this is the most constructive policy the United States has ever had towards China. It is constructive because it aims to put China on her own feet so she can become a base for peace in the Orient. It is a far cry from the Open Door doctrine which was motivated by equal opportunity, for trade without any constructive formula for peace. It is also a far cry from the Nine Power Treaty which depended on the balance of power and the status quo instead of the Chinese themselves to preserve Chinese integrity.

Some people still doubt the wisdom of relying on China for such a base. True, China at present does not have the necessary military power, industrial strength, or political stability. But the fact remains that certain prerequisites are already fulfilled. She is the only possible country in the Orient to check Japan if she should prove incorrigible. With lost territories restored and unequal treaties abolished, she has achieved juridical equality with other powers. She is the only Oriental representative in the Security Council. Beyond any doubt all Oriental countries, including Japan, now look upon China as the symbol of their future—what becomes of China willbecome of them. Chinese leadership in the Orient is a foregone conclusion. Lying directly between Russia and the United States, she is inevitably the arena of either cooperation or conflict between the two greatest powers. Which way China swings, whether in war or in peace, makes a tremendous if not decisive difference. Besides, there is the traditional friendship between China and the United States, which is a far more reliable tie than any alliance.

At any rate, the United States is going forward with the policy of transforming China to be a base for peace in the East, and General Marshall is implementing that policy with remarkable success. His plan of nationalizing the separate armies is being realized. A coalition government is only a matter of weeks. Regretfully his plan is being interrupted by the recurrence of civil war. However, the civil war is no longer a war between twenty war lords as in the Twenties. There are still many war lords in China but none has a private army, a special territory, or a separate regime to challenge the Central Government. Nor is the civil war fought for personal gains. It is now fought between two political parties for political power. This being the case, some compromise and settlement are bound to be reached sooner or later.

Once a national army and a coalition are realized, one great service the United States can render China is to foster the growth of liberalism. One encouraging aspect of the present situation in China is that liberal and intellectual elements both in and outside political parties are gaining influence. History has clearly shown that whenever relatives of emperors, eunuchs, and military men ruled China, she declined. But whenever educators, liberals, and intellectuals gained power, China soared to great heights. In the present Political Consultative Council, nonparty intellectuals have more representatives than either the Nationalist Party or the Communists. Within these two parties, liberals are becoming a stronger force. Once they gain control of the government, democracy in China will be assured and China will be well on her way to become a base for peace.

The central problem in the Chinese situation is Manchuria. China cannot exist as a strong nation, much less as a base for peace, without Manchuria. Over 90% of the population in Manchuria are Chinese. Manchuria is Chinese historically, geographically, politically, and culturally. Some 80% of China's coal and iron is either in or near Manchuria. With Manchuria China can hope to become a United States industrially speaking. Without Man. churia the best China can hope for is to become an industrial Italy. Furthermore, in the last 900 years practically all the conquerors of China either came from Manchuria or through it. Without it China can never enjoy a sense of security. If either Russia should control Manchuria or if the Chinese Communists set up a separate state there, a full scale war will inevitably ensue. The United States, and the United States alone, can prevent this terrible eventuality, by insisting on full Chinese sovereignty in Manchuria, all the better by repudiating the Yalta secret agreement.

But, in this new Sino-American relationship, we must not be satisfied with a new official policy towards China, however constructive and enlightened it may be. After all, the new relationship is a relationship between the two peoples. The final responsibility is theirs. In this connection the best thing Americans can do for China is to understand the Chinese.

Americans are much better informed about China today than twenty years ago. But along with increased information there is a distressing lack of clear understanding. Take for example the most favorite subject, Chinese corruption. Practically all items about Chinese corruption reported in American publications are correct. But from these facts, reporters, and commentators and popular writers who echo reporters, draw the conclusions that the Chinese are sinking morally, that the Chinese are by nature corrupt, and that therefore China is hopeless. Such misinterpretation not only does the Chinese a great injustice, but insofar as it causes Americans to lose faith in China, it may sabotage the American policy in China and therefore prevent peace. I have not the slightest intention to defend Chinese corruption. Every self-respecting Chinese condemns it as a national disgrace and hates it. But facts must be interpreted correctly, with a proper perspective. If we do so, we shall find that up to the middle of the 18th century, the Chinese government was clean and efficient, so much so that it was regarded by European writers as a model. It was only in the last 150 years that the Chinese government became corrupt. Confucianism was senile and had lost its uplifting influence. The Manchus did not have enough culture, experience, or even personnel to rule China, and they had to resort to having Manchu and Chinese officials check each other. Instead of checking each other, these officials became conspirators. Hence favoritism, nepotism, and bribery. The Manchus tried to appease the Chinese by offering Chinese scholars academic degrees which entitled them to governmental positions. Eventually there were more candidates than positions, and the pressure to get into a position was terrific. Hence more favoritism, nepotism, and bribery. Chinese population increased fourteen times in a hundred years while land expanded only 40%. The dikes of the Yellow River were out of repair. It overflowed often and became China's Sorrow. China lost several wars and had to pay huge indemnities. Poverty bred more corruption. On top of all this, there were eight years of war. As a result, as one Chinese wit put it, the most regularly declined verb in the Chinese grammar is "squeeze." "I squeeze; you squeeze; he squeezez... "

Viewing Chinese corruption in a broad, historical perspective, we are forced to conclude that corruption is not the result of racial characteristics but the result of economic and political chaos and that China is now at the end of the wave of corruption. While there is still much corruption, there is much less now than twenty years ago. In my student days one war lord squeezed $20,000,000 and got away with plenty of "face." Several years ago the mayor of Changsha squeezed half a million dollars inflated currency, and he was executed. No, China is not sinking morally. (Shall I add that recent Chinese corruptions are peculiarly Western in technique?)

This example shows how important true understanding is. It is here American colleges can make a real contribution to the new relationship between China and the United States. It is encouraging to learn that at present, of the 215 colleges and universities which answered an inquiry, four are offering 10 courses exclusively or largely on China, nine offer six to ten, 27 offer two to five, and forty offer one. But it is discouraging to find that in the wellheralded recent reorganization of college curricula in favor of general education, China, like all non-European areas, is almost entirely ignored. In the celebrated lists of "great books," Chinese classics are conspicuously absent," as though Confucian, Taoist, and Buddhist classics were not great, or had no influence in history, or the one-fifth of the human race whose lives are shaped by them did not exist. To be sure, there are famous centers of Chinese studies in the United States, but we must not be content with training a few specialists. There are also Chinese departments and courses in various colleges, but we must not be content with these as side shows. What is needed is a global concept in all courses, in philosophy, art, religion, music, government, economics, sociology, etc. This is to say that China—and all other large and important regions of the globemust be included in these courses.

Furthermore, hitherto American studies o£ China have been primarily from the viewpoint of trade and diplomatic relations, as if China existed essentially as a market and a pawn in international politics. The most widely used textbook on modern Far Eastern history was written from precisely this point of view. This approach is neither consonant with the spirit of the new relationship nor consistent with the ideal of liberal education. Fortunately good books on China are now coming out, notably those by C. L. Goodrich and K. S. Latourette—treating China as a human family with a historical and cultural entity. What is urgent now is to inject this liberal, human, and global spirit into the whole fabric of American education.

China has not received fair attention in various college departments because American professors hesitate to handle strange subjects outside their specialized fields. Modesty is a virtue for all people, especially college professors. But we are building peace, and there is so little time. Departments must become global even if professors have to depend on secondary and tertiary sources. Experts will emerge if there are enough amateurs and volunteers. In the mean time, the global spirit is in itself a liberal education, and understanding of other peoples will be increased.

There is another thing American colleges can do to promote the new SinoAmerican relationship, namely, exchange of professors and students. There is no surer way to world peace than to have young people of all races live together, young people who have no ax to grind, whose minds are still open, and who are idealistic. As they grow and study together, no racial or religious difference can prevent their understanding. The same can be said of professors. One of the best things ever done in international relations is the United States refund of Boxer Indemnity to China for educational purposes. Thousands of Chinese students have been educated in the United States on Boxer scholarships. The refund has achieved two amazing results. It has given China a remarkable leadership. It has also created for the United States inexhaustible Chinese good will.

Both the United Nations and the State Department are promoting these exchanges. But the final responsibility, so far as Americans and Chinese are concerned, must lie with the peoples themselves. And higher educational institutions should take the lead.

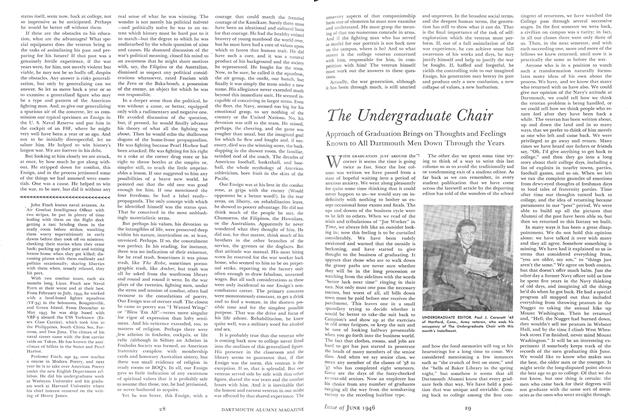

PROFESSOR OF CHINESE CIVILIZATION AT DARTMOUTH, Dr. Wing-tsit Chan came to the College nearly four years ago and has since lectured and written extensively in an effort to interpret his native land to America.

PROFESSOR OF CHINESE CULTURE

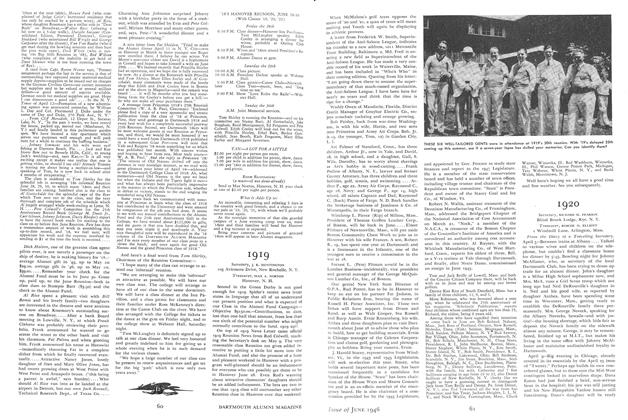

INTERNATIONAL EXPERT SPEAKS ON CHINESE-AMERICAN RELATIONS—That is the headline one finds week after week in New England newspapers and indeed in newspapers as far south as Tuscaloosa and as far west as Cleveland. This is not to say that Professor Chan is unknown in Canton, Manila, Honolulu, and Geneva. One of the busiest men on the Dartmouth faculty, Dr. Wing-tsit Chan, who got his doctorate at Harvard as far back as 1929, is forever catching trains to speak at dinners, conventions, museums, and learned societies about Chinese art, literature, music, and politics. Nothing if not versatile, Dr. Chan in Hanover straddles three departments: Chinese Civilization, Comparative Literature, and History. He does not teach the Chinese language, and the Chinese language is not at present offered in the Dartmouth curriculum. Professor of Chinese Culture at Dartmouth. Dr. Chan is our main cultural link with our great ally, that extensive dominion of Eastern Asia covering some four and a half million square miles of territory with a population as large as all Europe's. Forty-five years old, he came to Dartmouth in September 1942.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Class Notes

Class Notes1918

June 1946 By ERNEST H. EARLEY, DONALD L. BARR -

Article

ArticleThe Show Went On In Spite of Wartime Setbacks

June 1946 By HENRY WILLIAMS, -

Article

ArticleUnited States Foreign Policy and Europe

June 1946 By JOHN C. ADAMS, -

Article

ArticleA Hard Job of Education A Hard Job of Education

June 1946 By JOHN W. FINCH -

Article

ArticleRussia and the United States

June 1946 By OLIVER J. FREDERIKSEN '16 -

Article

ArticleOur Latin-American Foreign Policy

June 1946 By VICTOR G. BORELLA '30

Article

-

Article

ArticleA REPORT ON FINANCES

December 1943 -

Article

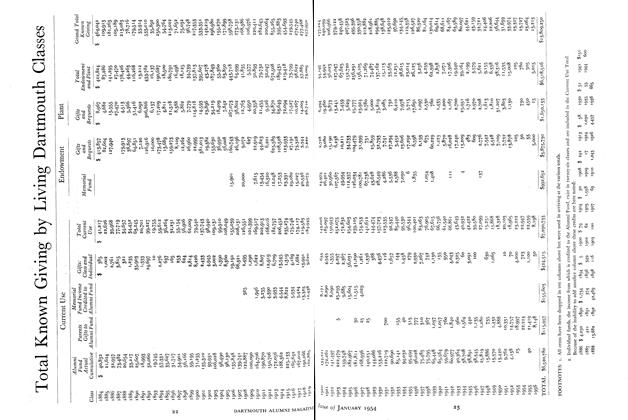

ArticleTotal Known Giving by Living Dartmouth Classes

January 1954 -

Article

ArticleBriefly Noted

JANUARY 1968 -

Article

ArticleDartmouth Authors

DECEMBER • 1986 By C. E. Widmayer -

Article

ArticleFRESHMAN REPORT

APRIL 1970 By JACK DEGANGE -

Article

ArticleThe 25th Anniversary

June 1941 By The Editor