THE AMERICAN PRESS today is the greatest and freest in the world.

That is merely stating the obvious, for a glance around will show that in many lands the censor and the government wield a power which came to full bloom in the World War II days. Even in Britain, where the press always has had a vast measure of freedom, there is afoot a campaign attacking the great London papers as monopolistic; and there exists more than a suspicion that this is designed to weaken or discredit press power and influence. It worked in Hitler Germany; it probably won't in England.

Some may quarrel with the opening statement as to the extent and nature of the American press, for in late years it has been more or less popular to view the American press with alarm—or scorn. Lest we appear to defend the press without exception, or appear to claim that all publishers grow wings, let us hasten to say that the press, of course, has its shortcomings. Some of these may not even be excusable as sheer human fallibility. Some may be rooted in such regrettable common human failings as human greed or human weakness or, sometimes perhaps, in just human cussedness.

May we grant these things yet make allowance for these human equations. Taken as a whole, the American press is constructive, fearless and infinitely more informing than any press elsewhere on the globe. And, if one is inclined to quarrel with editorial viewpoints in some newspapers, it must still be realized that information (news) itself is the newspaper's greatest and most beneficial commodity. For upon information, democracy functions. Dictatorships function on misinformation and distortion.

Certainly, American papers as a whole carry unadulterated news and a great volume thereof.

It is asked: "What is the job of the press in a democratic society. Should it reflect public opinion or form it." The answer may be given thus: The press should form public opinion, both by informing the public in the news columns and by guiding it in the editorial columns. To put it in another way, the press has the duty first to make the public aware of what goes on in the community, local, state and national; and, second, it has the duty to lead rather than to follow. Some newspapers may, as a colleague of ours suggests, "like to play God." But this is scarcely a fair general charge against the newspaper or against the duty that devolves upon it. Certainly within the limits of its capabilities, it should be helping the public to reach conclusions vital to the functioning of democratic society. This it may do through its major function of reporting what happens in the world, and through the expression of opinion or comment upon events. The magnitude and complexity of fast-moving questions swarming in upon the average man today result too often in a tendency to shrug them off with the comment, "There's nothing I can do about that." Of course, that may be true to a point, for it is certainly obvious that no man, with a living to make, can find time enough to master many of the intricate problems of a 1947 atomic world.

There the newspaper performs a valid and valuable service. It keeps the citizen posted, generally, on the major issues. And it can stimulate or guide his thinking thereon by careful, informed articles or editorials. Comments of experts—on both sides of a controversial issue—and the views of thinking citizens find a place in the modern newspaper and help in the democratic process of providing the people information upon which to base their own judgments.

The late, great columnist, Raymond Clapper, used to say, with sound wisdom, that a newspaper should never underestimate the intelligence of its readers nor over-estimate their understanding (information). In other words, if newspapers present adequate news and views on the world's happenings, the native intelligence of most readers will, sooner or later, come to sound conclusions. The motto of the Scripps-Howard newspapers, which this writer has the honor to represent, is "Give light and the people will find their own way.".

Incidentally, newspapers sometimes forget that simple words and presentation are the most effective. There is too much tendency to assume that a reader knows all the "big words" and that he has retained all the facts that went before in a given situation. In that process, many newspapers fail to be as informative or as helpful as they might be. But it is interesting to know that more and more newspapers are taking note of these defects and attempting to correct them. Sometime ago, newspapers became aware of lacks in their typography or "dress." Much has been done to correct faults in that field. And, now, considerable thought is being given to "content," to simplification and easy understanding. Short words, short sentences, short articles, pictures and larger type are some of the means of "getting across" facts essential to a reader whose time is limited but who wishes to know about things important in a democratic society.

We have now seen some elements of what the press does, and can do, to meet its responsibility to the community in this fast and furious age.

And now the question arises as to a definition of a "free press" and the further question as to whether we have one in the United States today.

In our book, a free press is a press free to publish what it chooses (within the limits of good taste and minus libelous utterance) without check or interference from governmental authority. Of course, there are those who harbor the notion that not governments, but advertisers or other impressive interests, determine actual freedom or slavery of the press. It may surprise some to know that, as a matter of fact, such editors and publishers as are timid, shiver more about pressures from their reading public than from the counting room.

But it is to be borne in mind that a publisher with a strong paper backed by public confidence needs have little or no concern about inappropriate pressures, whether from private or public vested interests. As a matter of ordinary operation, most papers hear little or nothing from their advertisers about what gets into the news columns. The writer recalls an instance of advertiser "pressure" with an amusing finale. This advertiser telephoned the paper one afternoon threatening to "make it personal" with the managing editor should the paper print a story of a small fire in his store. He was abusive and threatening. When the matter came to the editor's attention, the order went out to the news room: "Be sure that fire gets into this next edition." The order was carried out very thoroughly. In fact, so thoroughly that the little story got into the paper not once, but twice. That advertiser said no more then, or later.

On the other hand, there never has been a time when any government was fully happy about "freedom of the press." Officials might give the principle some Fourth of July cheers, but please be assured there are always authorities who do not relish press freedom, particularly when, in its course of informing or guiding, it shines a glaring white light upon a government department or official.

There are cases serving to illustrate our contention that many governments and government officials, left to their own devices, would be more than happy to place curbs upon the press. Such curbs would free them from the annoyance of editorial criticism, or what is worse for such people, the unfavorable public reaction stemming from criticism or exposure.

Make no mistake about it: public officials, as a class, do not love the press. Oh, of course, some do. And most of them confronted with this positive statement would undoubtedly deny it. They might even tell you they're very fond of the "newspaper boys," or that some of their best friends are newspapermen. But listen when they express their real reactions and you may ascertain that our statement is not exaggerated.

Earlier in this article there appeared the comment.... "in late years it has been more or less popular to view the American press with alarm—or scorn." In fact, a sort of cult grew up promoting the "scorn." We know a man who now for many years has made his living, or part of it anyway, by such a campaign against the press. Never too particular on the point of presenting the pros and cons, he cites lurid examples to argue that the press is unworthy of trust.

This is only one man, but he has helpers.

In fact, some attacks on the press in recent years were rather carefully nurtured in Washington from on high. True, some newspapers hit below the belt on occasion. But the generalities in which these attacks were answered, often contained broad and bitter condemnations which simply did not apply to the whole press.

But the important thing in this unfortunate warfare was that a segment of the public took up the Washington cries as gospel, and turned venomously on papers. This group fostered the claim that newspapers were vicious and had lost the confidence of their readers when the latter continued to vote the administration back into office even unto the fourth term, despite many papers' counsel to vote for another deal.

Let us look at this a bit more. It is a fact that many American papers can be listed as "conservative" or Republican. But, in a democratic society, there is no crime in being either conservative or liberal, Republican or Democrat. So the fact that many papers followed lifelong bents did not mean they had lost readers' confidence, nor did it mean, by a long shot, that they were vicious simply because they refused to follow the popular election trends. But the clamor group, taking cues from Washington scorn and sneers, would have it that our press was corrupt because it didn't ride the bandwagon. Some anti-administration papers adopted unpleasant tactics, on occasion, but the indictment raised against the press in general was wide of the mark.

President Franklin D. Roosevelt undoubtedly believed his courses in dealing with the press were right and good. When as a young press association reporter we covered his offices in the Navy, we knew him as a man with a delightful personality, who could "charm a bird out of a tree." Newsmen liked him immensely in those days and in his early White House years. But, in time, he became petulant and sometimes indulged in bitter criticism that, to speak frankly, was too frequently shaded with vindictiveness. He became impatient of criticism. Some of his reactions to criticism were very human. But, at the same time, they often did a disservice to the cause of good public judgment by casting unjust doubts upon the accuracy or integrity of the press.

Yet it is a fact that his words and deeds were fully and accurately chronicled. Even papers opposed to him gave full news of his administration. And, the further fact should be noted that, even though there are fewer papers today than some years back, it is still possible to pick and choose between liberal and conservative, Democrat and Republican, fair and unfair. Unfortunately, many people choose to read only congenial news or comment. As a nation, we seem unwilling to expose ourselves to uncongenial, or shall we say, contrary views. Our thinking and our judgments would be better were we to seek more after both sides of public issues.

But whether the press is as bad as some of the cult would have us believe, or as good as this writer regards it, there can be little doubt that, as a nation, we would be in a sorry plight were we to have a press like Hitler's or Stalin's. There suppression, distortion, utter misrepresentation were used to further the dictator's ends.

Better, in our judgment, that there be a few papers run by fools or crooks than that there be papers run only by a government.

A government, no matter how benevolent it may regard itself, is not to be trusted with control of the organs of news and opinion. In the end, only one opinion filters through such a press. That is the government's opinion and the government's slant on its doings.

A government in such circumstances never gives itself the worst of the deal.

Now to turn to another question arising from consideration of the place of the press in a democratic society: Is the profit motive compatible with impartial and full coverage of the news? Some of our earlier observations would tend to give yes as a reply. Let us make it here a very definite yes. In fact, the profit motive, far from being a sinister force in newspapering, is a definitely beneficial factor. A paper cannot continue long to exist if it is anemic financially. If it makes good profits, it can the more readily be strong and independent of undue pressures than if it is so poor and feeble that it is tempted to compromise with conscience.

Most politicians, most businessmen, most of the public—be they saints or sinners- know that they do well not to monkey with the buzz saw of a strong and fearless paper. And, in our humble judgment, a paper with good profits is in a position to be that sort of paper. True, some are timorous even in that situation. But they are not the majority.

And, more than incidentally, the paper with good income can afford better and more reporters, better and more news service, better and more features, columns and special articles. So their financial strength almost inevitably leads to a better news product.

No, that's one thing the American press need not be ashamed about—making a profit. Only when we come to some system other than the private enterprise system will it become reprehensible or unnecessary to make a profit. In the code of the "cult" mentioned earlier, it also was fashionable to cast suspicions upon the mere making of a profit. Making profits may, of course, be accompanied by unethical practices, but it does not follow that profit making is, by and of itself, a dangerous or an evil thing. A newspaper that makes a profit because of its public acceptance puts itself in a better position to serve that public than a paper whose waking moments are harrassed with fear of deficits or with apprehensions. of grief from treading upon sacred toes. There have been papers that were "bought and paid for" to promote interests other than the general welfare. But they almost inevitably came to grief. The public, in the long run, may get "off the beam" for a time but, sooner or later, it learns whether its newspapers tell it to them "straight."

Papers today are at their highest price in history; and their circulations are bigger than ever. If public confidence had disappeared, this would scarcely be true. The thirst for news—and newspapers—is deeper than most people realize. In fact, we in the newspaper field have never known until recent years—when the strike fever closed papers in some cities—just how deeply attached the public was to its daily papers.

And now a glimpse ahead. Is there any trend in the American press today; and to what may we look forward in the next 25 years?

Many of us wish we knew the answer. Perhaps there won't be papers, at least not in their present form. Facsimile is already here, and while, at the moment, it doesn't appear feasible, time and refinements conceivably can make it the newspaper of the future. That would not necessarily mean radical change in content. It would mean elimination of present fabrication methods—the linotypes, stereotype apparatus, presses. Every home and office would become, a publishing plant as the day's grist of news, editorials, pictures, comics came over the wire to the facsimile printer.

There are trends which probably will be accentuated with time.

Many newspapermen think the press will turn increasingly to "service" to communities, working more intimately for development of these communities and more thoroughly for the interests of the citizens. That is a definite trend. And there is an increasing conviction that the newspaper will become more "local" in its news coverage without, however, neglecting the broad fields of national and international news and interpretation.

Development of news and articles of special merit and interest will grow. Perhaps as great a weakness as the American press has today is that of uniformity. Many features, columns, comics are to be found across the country. There is perhaps too much "standardization." Watchful editors are giving thought to employment of more "specialists" who shall cultivate news and articles in their given fields, as government, labor, housing, welfare, science, travel. The tendency is to greater "interpretation"—that is, a wider offering of the "news behind the news" or the "why" of governmental and other happenings.

Newspapermen know that standing still only means death. They are widening their horizons. The newspaper of the future will be more interesting than ever before, more enlighteningly helpful in the new supersonic and atomic age.

EDITOR OF THE CINCINNATI POST

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Class Notes

Class Notes1918

February 1947 By ERNEST H. EARLEY, DONALD L. BARR -

Article

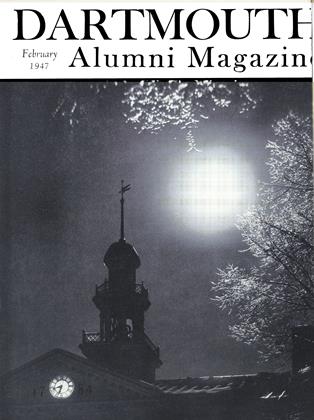

ArticleYour Newspaper and You

February 1947 By CLAUDE A. JAGGER '24 -

Article

ArticleA Free Press?

February 1947 By A. J. LIEBLING '24 -

Class Notes

Class Notes1943

February 1947 By FRED F. STOCK WELL, WILLIAM T. MAECK -

Class Notes

Class Notes1928

February 1947 By OSMUN SKINNER, RUPERT C. THOMPSON JR. -

Class Notes

Class Notes1917

February 1947 By MOTT D. BROWN, DONALD BROOKS