Changes Resulting from New Power Dam Near Hanover May Make the College River-Conscious Again and Open the Way for Expanded Activities

SLOWLY THROUGH the years, as Dartmouth has expanded and taken modern form, the campus has grown away from the Connecticut River and the undergraduates have become less and less river-conscious. For many, it requires an effort to recall that Dartmouth was completely a river college in its early days and that even now it is entitled to that description. The completion of Baker Library definitely anchored Dartmouth to the present College Green, for the library is not just the geographical center of campus; it is also the psychological center and serves both as the dominant landmark and as the hub of college life.

The Connecticut, however, is not a dead issue. On the contrary, changes are about to take place that may revive some measure of river-consciousness and that almost certainly will make the Connecticut an even more impressive natural asset to Dartmouth than it is now. Time and the manmade changes resulting from the new damming up of the river near Hanover may go so far, in the end, as to give Dartmouth a river campus undreamed of today.

Early last November, after several years of extensive hearings, the Federal Power Commission approved the construction of a dam to be built on the Connecticut River just below the present Wilder Dam. Its completion will add another chapter to the record of the economic development of the river and its dependent peoples and at the same time offer the College the opportunity of realizing the Connecticut as an integral part of an already beautiful campus.

Sometime this summer, under the supervision of the Bellows Falls Hydro-Electric Corporation, construction will begin on the new dam, the largest yet built in this area. Its ramifications will be widely felt, especially within the valley from White River Junction north to Woodsville, some 46 miles by river. The effect on Hanover and the College should interest Dartmouth graduates and undergraduates alike, for the resultant change in the river will substantially alter one of the few landmarks that have existed in their present state since the College was founded.

The new dam is to be built at the Wilder Narrows, approximately threequarters of a mile below the existing dam, raising the river level at Ledyard Bridge an estimated 16 feet above its present mean level, and creating one of the longest manmade ponds on the Connecticut.

The effects of the rise in the river level can be stated in a fairly short space, and with reasonable assurance that they will follow as predicted. The effects on Dartmouth, however, are part fact and part conjecture.

In the valley, the rising water will inundate more than 1100 acres of land, 335 of which will be tillable or actual farm land, and 810 river bank, non-tillable or pasture and woodland. This might at first glance seem relatively little, yet, considering the amount of actual tillable land in 46 miles of valley, and the fact that the tillable land to be flooded is some of the richest in the valley, the loss is not inconsequential.

The College, on the other hand, will lose relatively little land through flooding, owing to the precipitous nature of the river's east bank between Mink and Girl Brooks.

But the river's west bank, opposite the College holding, and the land on both east and west banks above Girl Brook will be extensively affected. Then, too, there are three islands below Ledyard bridge either owned or controlled by the College that will be all but covered. Mink Brook and a greater part of its valley will be flooded as far upstream as the West Lebanon Road, creating a sizable pond. North from Nigger Island to Ledyard Bridge, the river will widen to the westward, flooding a good portion of the lowland immediately below Lewiston and necessitating the removal of at least five houses in that village. Narrowing at the bridge, it will widen again on the Vermont side, requiring the raising of the road that runs north between the railroad and the river and in several places even reaching the Boston and Maine railroad embankment. Ledyard Bridge will probably have to be raised, though how much is still in doubt.

Girl Brook as it winds its way west through the golf course, then north through the Vale of Tempe and west again through Pine Park, will be flooded almost up to the old ski-jump. While the level land in Pine Park, that part at the foot of the ski trail that runs along Occom Ridge, will not be covered, a portion of the lower land will be, necessitating the removal of a number of trees. All in all, the Hanover area will get an appreciable increase in both the depth and width of the river. The riverscape will be greatly changed and open to the development of what may become one of the most beautiful river campuses in the East.

As the plans stand at present, the College as a whole and several of the student organizations in particular should benefit enormously from the rise in river level. Considerably wider and deeper, the river should flow much more slowly, thus lengthening its period of usefulness for the Canoe Club and crews, and for the individual student who is not connected with these organized groups.

Slower water and the increased width should be of particular interest to those who have had a hand in reviving crew at Dartmouth, for the sport's full scope can be realized only by the creation of such a body of water. Then too, the river will be much more accessible; in its elevated state it will eliminate much of the present difficulty in launching shells, and the construction of a new pier or landing stage espe cially designed for shells will complete the picture. Proper facilities are almost certain to produce much greater student and alumni interest in crew as a Dartmouth sport.

The Canoe Club will benefit from the rise in river level as much as will the crew, for the clubhouse will then be but a few feet above water. This will, of course, necessitate the construction of a new pier, a problem which should be outweighed by the fact that the chubbers will no longer have to wrestle a wet and slippery canoe up and down some twenty feet of winding and precarious steps. Both the Canoe and Outing Clubs may acquire, if only temporarily, a new pioneering spirit, for there will be more than a thousand new acres of river to cover and new camp sites to be built.

Mink and Girl Brooks will be but a short paddle from the clubhouse; in their new state they will be quiet bodies of water overhung by pines and hard woods, places where an old grad can recapture some of the memories of a spring night when he, like his son, willingly shelved his books for a smooth ash paddle and a light two-man canoe.

How much the Yacht Club will be able to utilize the river is still in doubt; probably not for actual races. The river will still be too narrow for a good course, but it may well afford yachtsmen a good place to practice, thus eliminating the necessity of running down to Mascoma whenever the chance to sail avails itself.

Whether or not the river may be used for ice skating remains to be seen, dependent entirely on whether or not the current will be slow enough to allow even and smooth freezing without pressure cracks.

Future fishing on the river will hinge on two possibilities, neither of which will be worthwhile without the other. The first is the inclusion of a fish ladder which, if built in the dam, would enable fish to pass up and down stream as is their natural habit. Without it, valuable and necessary spawning grounds .would be denied fish downstream, leading to the ultimate destruction struction of fish life on both sides of the dam. The second is the matter of sewage disposal.

Sewage has heretofore been dumped into the river without much, if any, restriction, and while thus far fish have suffered relatively little, this can be attributed to the fact that the rapidity of the flow suffices to carry sewage down river and past the dam. With the new dam, the problem may well become acute, with higher spillways, increased depth and slower current. Greater dilution of sewage may, however, be a compensating factor.

Should these result in the destruction of aquatic plant and animal life, and in turn result in positive pollution of the river, there would be a new problem. The answer to this would be a sewage disposal plant, which aside from keeping the river clear of contamination, would make it far more beautiful and might possibly furnish the area with a decent place in which to swim.

There are tentative plans for the development of a trail, running from the Canoe Club north along the river side of Occom Ridge to Girl Brook—if, of course, property owners on the ridge permit it. It would serve a twofold purpose: with proper care it would make an ideal and natural gallery from which to observe the crew races, and the College's already beautiful campus would be immeasurably enhanced by year-round access to the potential beauties of the Connecticut, a walk in the spring, summer and fall, and a skitrail in the winter.

While there are no plans other than have been mentioned for the development of what might well come to be Dartmouth's River Campus, there is room for the construction of a lodge on the land between Tuck Drive and the river where the Ledyard monument stands; a place for postrace dances .in the spring and fall, a spot that could come to be for the students what the Outing Club House at the head of Occom Pond is to visiting alumni today.

With all these influences which the new dam may possibly have on the College, it may also stir up in Dartmouth men a keener interest in the river which has flowed ceaselessly past Hanover Plain since long before Eleazar Wheelock searched it out.

Rising in the Northern New Hampshire Lakes Region, the Connecticut flows southwest, then south, some 400-odd miles, dropping 1900 feet to its tidewater outlet on Long Island sound, its route a veritable highway in the historical and economic development of Central New England. Before roads and rail pushed their way north, the river was the only means of access to the rich and fertile tableland of the lower Connecticut Valley region and later the upper Connecticut Valley in which Hanover is situated.

With the increase in population, as more and more land was put into cultivation, came the succeeding introductions of sheep raising and woolen mills, lumbering and paper mills, the industrial revolution with its centralized plants whose power needs could be filled only by the utilization of water power.

At first simple grist and saw mills sprang up along the river and its tributaries, but the big change came with the advent of the paper and weaving industries and their demand for a greater, more controllable and steady source of power. To this end, a dam was the only answer.

The first dam in the Hanover-White River Junction Region and probably one of the first on the Connecticut was built just below the site of the present Wilder Dam early in the 1780's. Not a dam as we might picture today, it was a "wing dam" or partial block of the river creating an artificial and rapid flow of water, augmented in this instance by the White River Falls.

The power it developed was used for milling grain, sawing lumber and similar related purposes. In 1795 a charter was granted by the Vermont Legislature to a group of people calling themselves the Proprietors of White River Falls a charter which extended them the right to "lock," or to build a. canal around the falls, thus rendering the river navigable almost to its headwaters. For some reason, work was never started, but in 1807 a new company was incorporated under a New Hampshire statute entitled "An act granting to Mills Olcott the privilege of locking White River Falls." This act was followed in 1810 by the erection of the first complete dam, and later two separate canals and locks.

About 1849 the Passumpsic Division of the Boston and Maine Railroad was completed, the canals fell into disuse and a few years later a freshet carried away the dam.

In 1880 the water rights were acquired by the Wilder Brothers, paper manufacturers of Boston, and a cribwork dam was built at the upper falls in 1882. This dam was replaced in 1926 by the present concrete structure located slightly downstream. The power developed was utilized in the manufacture of paper until 1927 when labor trouble shut down the mill. The mill never reopened and the dam and its generators are today used solely to furnish electricity for the surrounding area.

With the new dam, there is, of course, the natural question of floods and the ensuing damage. While the new dam is not being constructed as a flood-control measure, it will, to quote an official of the company, "pass flood waters on as we receive them." All College dealings in connection with the dam and its relation to the College have been under the able direction of the College Treasurer, Halsey C. Edgerton. Mr. Edgerton, with his eye to the future, has carefully provided that any damage incurred by the College through changes in river levels or flood heights resulting from the dam will be taken care of by the owner of the dam.

There has been a good deal of opposition to the proposed construction of a higher dam: opposition, which for the most part, was both reasonable and constructive. As in any development such as this there are two sides—two irreconcilable points Of view.

According to the valley farmers, the consequent flooding will inundate a large amount of land, some of the best in the valley; the water table will rise, affecting adjacent fields and rendering them useless; there will be an appreciable curtailment of milk output in an area which supplies a good part of the Greater Boston milkshed; then, too, there has been no indication that power rates will decline.

The power company has its side too. The demand for power in the areas supplied by the present dam at times exceeds its present capacity. Completion of the new dam and inter-connecting transmission lines will insure a steady supply throughout the year. Taxes will be lowered in certain areas through the proportionately larger return the company will have to pay.

Inasmuch as the Bellows Falls HydroElectric Corporation received the stamp of approval of the Federal Power Commission, it is safe to assume that the new dam is both necessary and practical. It should also be noted, however, that there was little organized opposition to it. The farmers and valley people who opposed it were not diehards; theirs was a legitimate protest and it was only natural that they should fight to hold the land from which they eke their living. The few considerations they fought for and were awarded were fair and reasonable.

So the river will change. The next three years should be a golden opportunity for Dartmouth to plan and prepare for one of the biggest changes the campus has ever undergone in so short a period of time.

PETER E. COSTICH '47, author of this article on the new dam, poses against the backdrop of the present Wilder Dam. He lives in Westbury, N. Y.

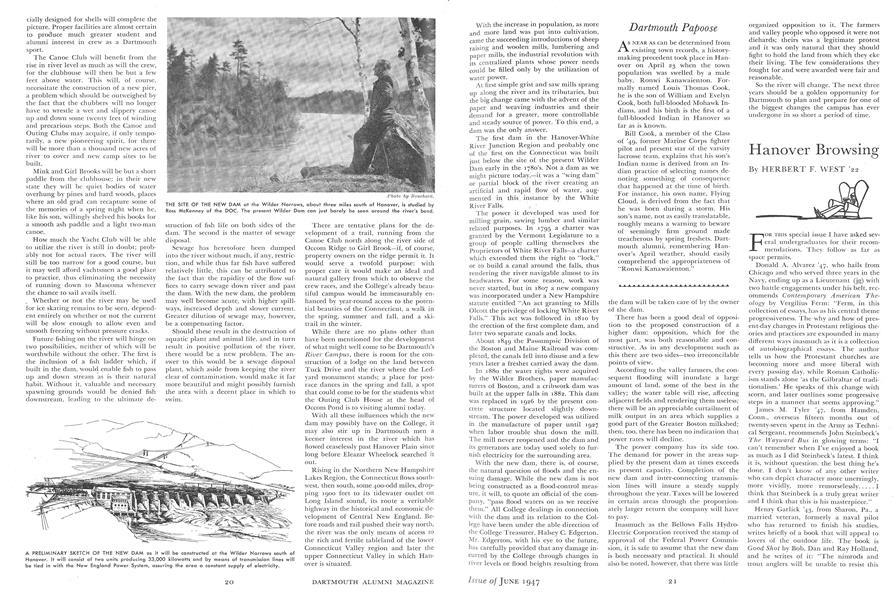

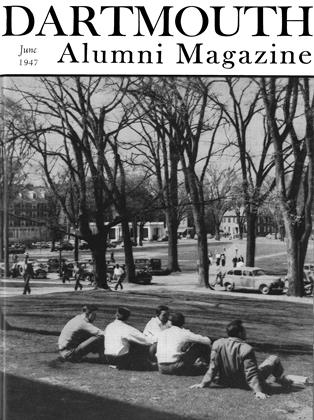

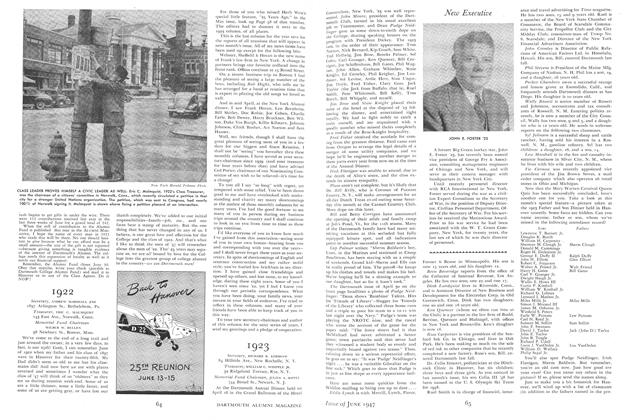

A PRELIMINARY SKETCH OF THE NEW DAM as it will be constructed at the Wilder Narrows south of Hanover. It will consist of two units producing 33,000 kilowatts and by means of transmission lines will be tied in with the New England Power System, assuring the area a constant supply of electricity.

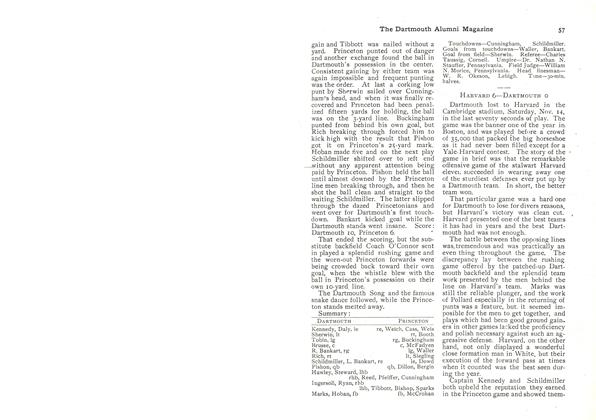

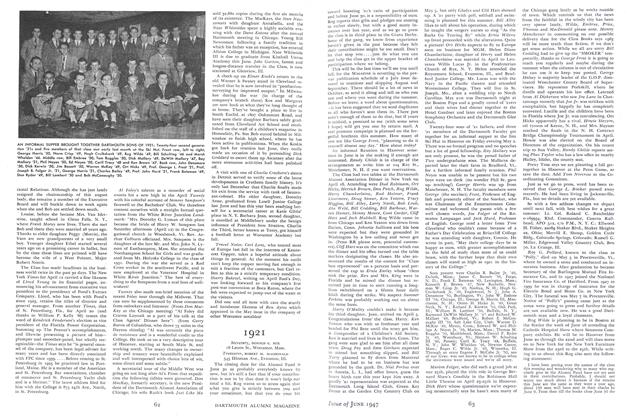

THE SITE OF THE NEW DAM at the Wilder Narrows, about three miles south of Hanover, is studied by Ross McKenney of the DOC. The present Wilder Dam can just barely be seen around the river's bend.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Class Notes

Class Notes1919

June 1947 By J. K. HUNTINGTON, MAX A. NORTON -

Class Notes

Class Notes1918

June 1947 By ERNEST H. EARLEY, DONALD L. BARR -

Class Notes

Class Notes1921

June 1947 By DONALD C. MIX, ROBERT M. MACDONALD -

Article

ArticleTHE TIRED VETERAN

June 1947 By EDWARD F. EUBANKS '44 -

Class Notes

Class Notes1943

June 1947 By FRED F. STOCKWELL, WILLIAM T. MAECK -

Article

ArticleFACULTY HELMSMAN

June 1947 By JOHN P. STEARNS '49