TEN points for making a snow statue.We got fourth place. That's twopoints more. Houseparty list got in late;they'll take five points off for that. Now,let's see.

Someone in each Dartmouth fraternity will go through such mental gymnastics very soon, as a year of innovations produces another offspring. Its latest is the Dartmouth Fraternity Competition.

As the competition is presently constituted, houses will be ranked on four branches of their activities: administration, scholarship, non-athletic contests and athletic contests. A committee of three judges—the Dean, the Chairman of Faculty Advisers and the Interfraternity Council president—will award points, and the Alumni Board will give prizes, to first- and second-place winners of each division, and of all four as a whole. The ranking of each house will be announced and posted at the same time prizes are awarded, early in the fall.

Athletic and non-athletic contests include all interfraternity sports, and competitions like the Hum, play, debate, snow sculpture and bridge contests. In each instance, the plan emphasizes participation rather than relative success: entry points in all except the bridge contest are more than those given for first, second, third and fourth place.

Awarding the scholarship prizes is merely a matter of finding from the Registrar which houses have the highest twosemester scholastic average.

Indeed, only in the administration division has there been injected an element of public competition not already existing, formally or informally. A violation of College or chapter social rules, by members or non-members, in their own or other houses, will cost each house implicated—through the agent or the scene of the violation—a ten-point deduction from 100 points assigned to it when the competition began. Similar deductions exist for each dollar of unsettled accounts, bills or audits, and for each failure of chapter officers to submit lists and data to the College, to attend interfraternity meetings, or to give information needed by an interfraternity organization.

Hitherto, all the plan has done is to assign grades to activities in which houses engaged even in their old status. Obviously, that would not be enough to bring about the refinement which Board and College demand. The backbone of the competition, a design allowing chapters more acceptable outlets for their energies, is a totally new aspect of fraternity life— the project.

In the Board's words, "A project will consist generally of a detailed plan for an activity which will engage the interest of the whole chapter for one or more meetings." Within such broad limits, it would seem almost any group activity could fall. It can not.

In Dean Neidlinger's opinion, a cribbage tournament for the whole house would count as a project: a dance or beer party would not. In general, a project must be at least somewhat educational or useful. It will be awarded a number of points proportionate to its extent and usefulness. Thus, the cribbage tourney would net a small number; a long and serious endeavor, a large number.

"We are more anxious to get one-meeting projects," the Dean comments.

"If the men don't like suggested projects," he adds, "they can suggest things of their own choosing. Our ideal is a list of about 60 projects." Such a list could be kept permanently on hand and could be undertaken by each chapter without repetition in the three-year cycle of its membership.

IN A RATHER large nutshell, that is the Competition. Surprisingly enough, it took no house's breath away when finally adopted last month. By that time, in fact, it surprised no one.

For skepticism concerning the worth of fraternities here had been expressed long before the war. It came to a head on September 10, 1945.

At that time, alumni representatives of the fraternities, Dean Neidlinger, Professor Lindahl of the faculty advisers and Meryll Frost of the undergraduate body had answered the call of George M. Morris '11 to a meeting in New York. Their purpose was to discuss ways and means of reopening war-shuttered houses.

It was not all clear sailing for the houses. Prominent among the difficulties, and symbolic of the questionings in many minds, was a considerable movement among the representatives to solve the drinking situation by removing it bodily from each postwar chapter. Before demolition squads could be unleashed on every barroom, however, a majority of the men present agreed to a College compromise: bars would remain, but drinking would have to be on a better basis.

Even that left a few ghosts unlaid. As Dean Neidlinger puts it, the meeting went on to "rehash fraternity difficulties and the lack of any purpose which marked fraternity affairs o£ the pre-war period." Out of this rehashing was born unofficially the Alumni Advisory Board, composed of alumni representatives of all the chapters. It took on a permanent character at the time of the first postwar rushing, in March 1946.

Two months before that date, the still unofficial Board had met again in Hanover. And there again, the doubts came out in the generally expressed feeling that if fraternities -were to continue they must accomplish more—that, to assist the process, alumni influence should be brought to bear on the chapters, through the Board.

But the Competition, embodiment of that pressure, was not suggested until a third meeting in New York in September 1946, when Mr. Morris rose to outline a scheme of rating even more comprehensive than the one now in effect—too comprehensive, in fact, for the judges to measure and score.

And yet it also seemed too good to let fall of its own weight: Dean Neidlinger and Charles F. Camp '42, appointed in January as College Officer in Charge of Fraternities, worked until spring stripping off its excess poundage. Their second draft, with an invitation for criticism, was then handed to the Dartmouth chapters.

The chapters' breath, at this point, did leave them completely. It returned with a storm of protest.

Dartmouth Fraternities, with few exceptions, simply did not want to be rated in the proposed manner. Their main argument was that fraternities are social organizations, and should be considered only as such. Their merits are intangibles of social relations. Intangibles defy point scoring; therefore, so do fraternities.

Unfortunately, the question of rating was no longer one of yes or no. Too many years of "social relations" had gone down in College records—too many years of unpaid bills and over-late hours. The fraternity would be a more positive part of Dartmouth experience, or it would not be at all. The question of scoring was now only how.

Here chapter criticism of points for honors or offices attained by individuals, which might lead to politicking, was answered. Chapters thereafter were to be judged as units.

With this revision and others, a third draft was submitted to the Alumni Board at a meeting last September. Approved there, it awaited only Interfraternity Council recognition to go into operation. That is not to say that Council agreement was necessary—the plan would have started in spite of any unwillingness undergraduates might have expressed. But action was delayed until the Council could decide whether to be a joint sponsor of the system.

With little enthusiasm, the Council so decided, November 4.

Estimates of the Fraternity Competition's success now, when it has barely begun, would seem foolhardy. But a rough assessment can be made from the plan itself, and from current reaction.

In one sense, it will be an unqualified success. Because the scoring system can be carried on by foolproof outside observation of unconcealable actions, every house will be graded, whether it cooperates or ignores the Competition, as some may do.

But true success of the competition, I think, does depend on house cooperation. Negligence of a house may bring embarrassment to it when the reports are out, but neither that house nor the plan itself is helped by such publicity.

I think the forthcoming of cooperation highly problematical. And I think that the reason why it is not assured lies in the preparation, revision and final acceptance of the plan.

In all that process, undergraduates were given some hand. But, prejudged as futile and by past nature useless and sometimes detrimental to College purposes, the fraternities were never allowed to stop the plan entirely. Perhaps that is a good thing; perhaps it .was the only way. But men now in fraternities resent the fact that a system all but a few of them opposed has been imposed upon them nonetheless.

While those men are still in College, whatever cooperation they give will be half-hearted, based more on fear of alternative consequences than upon natural inclination. Until they, or a later group which knows no other system, catch on to the really positive aspects of the plan—the projects—you cannot honestly say it will accomplish its purposes.

That question must remain open.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Article

ArticleMEN VS. MICROSCOPES

December 1947 By JOHN HURD '21 -

Article

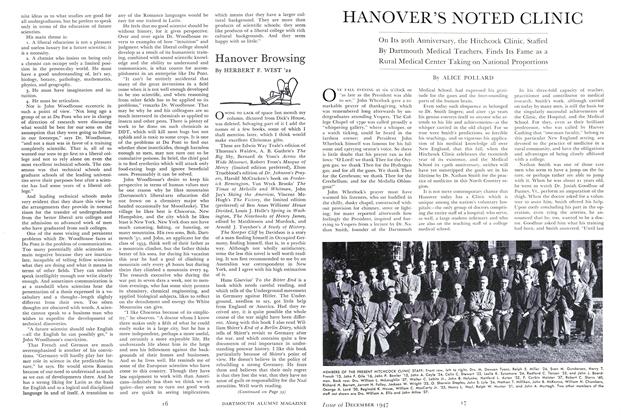

ArticleHANOVER'S NOTED CLINIC

December 1947 By ALICE POLLARD -

Class Notes

Class Notes1918

December 1947 By ERNEST H. EARLEY, DONALD L. BARR -

Class Notes

Class Notes1917

December 1947 By KARL W. KOENIGER, DONALD BROOKS -

Class Notes

Class Notes1919

December 1947 By J. K. HUNTINGTON, MAX A. NORTON -

Class Notes

Class Notes1934

December 1947 By FRANKLYN J. JACKSON

JOHN P. STEARNS '49.

Article

-

Article

ArticleDR. WHEELOCK'S ALMANACK.

MAY 1989 -

Article

ArticleHANOVER BROWSING

October 1935 By Herbert F. West '22 -

Article

ArticleThe Undergraduate Chair

JANUARY 1968 By JOHN BURNS '68 -

Article

ArticleLong Island

OCTOBER 1971 By MICHAEL R. PENDER '47 -

Article

ArticleThayer School

APRIL 1966 By Russ STEARNS '38 -

Article

ArticleMiscellany

October 1935 By The Editor