Albert J. Colton '47, in Valedictory to the College, Urges Fellow Graduates to Fight Prejudice as Foe of Democracy

Two YEARS AGO this summer brought to an end a war in which most of us now graduating participated. Two years of peace have done much to heal the angry sores of world-wide war, as most of these men can attest. There are marks of battle hatred, famine and disease, that can be well eradicated and forgotten. Yet there are many other things that cannot and should not be forgotten, for man has learned only through painful experience, of which war has been his most excruciating.

We at Dartmouth have been extremely fortunate, for we have had the advantage of returning for a few years to an isolated spot of peace, happiness and culture, during which time we could gain perspective on this world of ours. We have found here a small, beautiful, New England town which men from all parts of the country have taken to their hearts. We have found teachers who have not only helped us find new wisdom, but have also become personalities of their own, often close friends. We have seen the combination of geographical and personal factors that have made our school unique, and have developed a sympathy for her which better men than we have been unable to express. A sympathy which can be shown tangibly by the constant care and attention lavished upon her by sons who have graduated years before. And we have seen problems arise even in this idyllic environment—many of which we leave unanswered.

We graduating today represent only a temporary group upon the Dartmouth scene.... older, more mature, more intense undergraduates, wives and babies, troublesome grocery lists and interesting clothes lines .... novelties which perhaps have caused the world to give us what is undue respect and emphasis. The veteran does have an importance in our society, however, for few can say that he has not learned something from his war experiences— experiences which though distasteful for the most part, were at times educa- tional and enlightening.

However, some of us detect among our student veterans not a new enlightenment growing out of the edifying features of the war years, but rather a certain egoism, cynicism, together with a more materialistic philosophy. Such a trend is of course to be expected as the natural product of all of mankind's wars—but perhaps some of us were naive enough to hope that among men in an educational environment such would not be the case.

A small amount of worldliness serves as a healthy tempering for the steel of rash idealism, but worldliness can become a danger when it tends to destroy rather than modify. It is dangerous to a complex civilization when its potential leaders, students like ourselves, blandly accept the inevitability of another war, yet refuse to read anything of deeper international significance than British-American golf matches. It is ominous when we hear men openly scoff at any code of business or political ethics based upon anything but individual advancement, or when we find a college degree considered only a means to enhance money-making potentialities. If we permit trends such as these to develop into an egotistical free-for-all, what then becomes of our community and our heritage?

Fortunately, Dartmouth and its hundreds of sister colleges offer us a potential saving grace. It is here that we have an opportunity to see for ourselves the age-long tradition of the liberal arts. We have seen the beauties, the achievements, and the potentialities in man, as contrasted to the beast-like creature so many of us have viewed in times of war. Education has shown us tangible proof of a quality that we have sometimes recently doubted. It has shown us the reality of man's, dignity and the basis for an optimistic faith in the human spirit.

Our world has known few educated men. We graduating today cannot presume to provide the answer to the world's many problems. Yet, as with every man, it is our obligation to understand our world—to the man of education in the complicated so ciety of today, this duty becomes even more demanding.

Observation of the world around us shows that too often an attempt is not being made to understand. Can it be that we are developing the same numb indifference toward world problems with which the Italians living on the slopes of Vesuvius regard that still active volcano? Have we forgotten that our good fortune brings responsibilities too? Superior advantages should bring superior leadership, and we as Americans and Dartmouth men have certainly had an abundance of the former. Our lives, then, must not be a mere materialistic struggle for well-being, but should and must contain intelligent opinion and guidance in the affairs of the human community.

In the world of international politics the educated, democratic man must, I believe, be commended for his leadership in demanding liberal, progressive policy. He has favored strong world organization, lower tariffs, and the full assumption of international responsibility. His most commendable action has been displayed in the struggle for formation of atomic policy. Scientists have been joined by other educated men, whose inspiring battle on behalf of David Lilienthal and a liberal atomic policy was most heartening.

Yet, the rays of light that do exist on the international front are quickly extinguished when we turn to internal America. Here it has seemed that the forces of education have failed. Cynicism and hate cover every section of the country. Racial and religious intolerance in the "Great North American Democracy" makes embarras- singly effective reading to the peoples of the world, as the Communist press knows all too well.

Even many of the nation's educated have failed to realize that the accident of birth is the world's biggest lottery, in which most of us here today have held comparatively lucky tickets. Yet the educated man most of all should have an humble realization that the accident of birth and environment has given us no God-given advantages or prerogatives.

There are many who deny this. Through one of history's strange paradoxes, those classes with the best educational advantages have often fought political equality. Thus the fallacy of "inherent superiority" has arisen to plague democracy. It is a belief not confined to any one group—it has ranged from kings, through nobles and men of wealth, to the poor southern white. One cannot help but be amazed at its continued existence among those who have had education's finest advantages.

Prejudice of all sorts is a dangerous cancer upon the healthy community, not only destroying its victims, but the oppressor himself. It is he who is forced to become suspicious and narrow, fearful and untrusting of the world around him. He fails to realize that no man can lead a full life and a prejudiced one at the same time.

Today, when all over the world doubt in democracy has reached a new high, a nation of prejudices professing devotion to democratic ideals cannot long survive. Second-class citizenry and the Declaration of Independence cannot exist synonymously without the gradual and inevitable weakening of the democratic sanction. This will become all the more true the longer the killers of men like Willie Earle continue to live a life of security and approval among their fellow men of South Carolina. Democracy will grow progressively weaker as long as strong minorities exist who would reject a David Lilienthal or an Alfred Smith from-a position of national significance because of religious prejudice.

These cases are the more obvious, more outstanding side of the question. By far the more effective danger comes in a much more subtle way—by means of the social slight, the biting joke, and the casually mentioned words "nigger, kike, wop, or bead-roller." It is here that democracy is put to its most severe test.... in the world of everyday relationship, and it is here that the American must make his choice. Even at Dartmouth we must remember that as long as groups of men on campus bar students from the opportunity to participate in school activities, we are not living up to our obligations as democratic citizens.

Remedies to these questions can appear only from ourselves. It is up to each of us to decide the proper weighting of his life's experiences .... to decide the proper value of his college years and his years of war. We must ask ourselves—which of these two interpretations of mankind will color my thinking and action in life with my fellow men? Will it be the war-inspired cynic's belief in a beast-man, a selfish and ruthless thing that can only advance over the remains of conquered rivals; or the awakened, the potential man, a creature who has advanced far and who is capable of infinite development?

Or, must the matter remain that of a choice at all, but rather can we not as college men benefit from the two extremes, searching only for the truth reflected in both?

A healthy skepticism engendered by the war certainly cannot be deplored it cannot help but show us the psychological weaknesses of rampant liberalism, and help us to build it up anew, stronger, and more mature.

Yet the line where skepticism fades into pessimism is only vaguely drawn at best. Moreover, the world has had enough cynics. There is now need for a new, more positive belief. Communism cannot be fought merely by subsidization of reaction and a hatred for Russia. It is my belief that it must be combated with a new faith in democratic government.

A nation filled with prejudice cannot provide a new democratic faith. A choice must be made. Lip service to a democratic ideal will not alone maintain its existence.

It is here in the field of prejudice that we as graduating seniors must first begin our job, and cast our vote for a rejuvenated faith in knowledge and in man, and in the inspiring potentialities of the two combined. It is here that we must first direct our attacks against the forces of dictation.

Then, with a clear conscience, we can become crusaders abroad, but not until we and the American nation can say as a whole, without qualifying clauses and mental reservations, "We, the people of the United States."

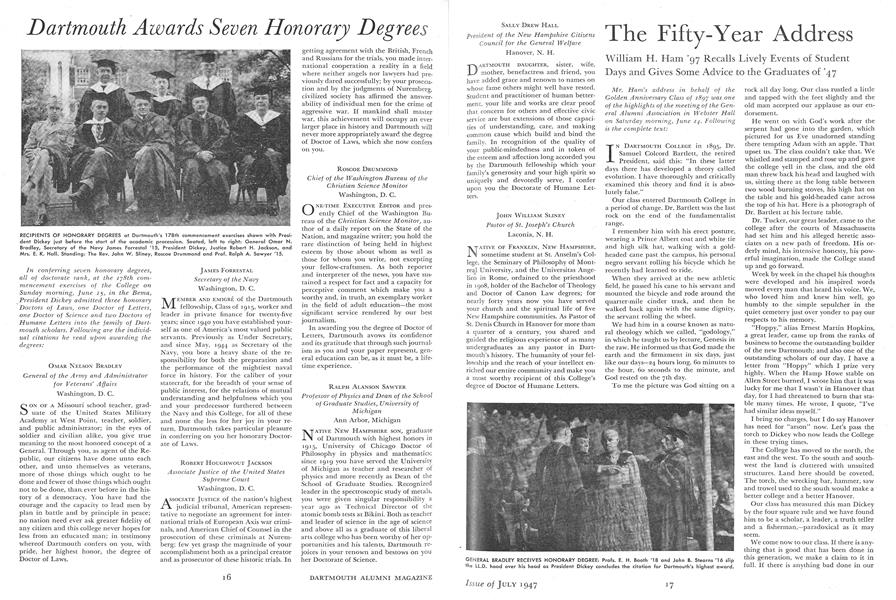

CLASS VALEDICTORIAN: Albert J. Colton '47 of Webster Groves, Mo., as he delivered the farewell of the graduating class at the Bema exercises.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Article

ArticleThe Commencement Address

July 1947 -

Class Notes

Class Notes1922's Super Twenty-Fifth

July 1947 By ANDREW MARSHALL II -

Article

ArticleThe Fifty-Year Address

July 1947 -

Class Notes

Class Notes1937 Holds First and 10th

July 1947 By ROBERT P. FULLER -

Class Notes

Class Notes1942 Holds First Reunion

July 1947 By JAMES L. FARLEY -

Class Notes

Class Notes1897 Its 50th Reunion

July 1947 By William H. Ham

Article

-

Article

ArticleTHE 1919-20 CATALOGUE'S FIGURES ON ENROLLMENT

February 1920 -

Article

ArticleA Wah Hoo Wah for –

July 1960 -

Article

ArticleTraynham to Move West

MAY 1983 -

Article

Article"Winter" at the Hood

MAY 1986 -

Article

ArticleProf's Choice

APRIL 1992 -

Article

ArticleThe College as a Cooperative Enterprise

OCTOBER 1931 By Ernest Martub Hopkins