Dartmouth's Sherman Fairchild Physical Sciences Center has come of age, after surviving an imperiled infancy. Ten years ago, a strikingly modern fourstory glass tower was built to unite two more traditional buildings housing science classrooms, Steele and Wilder, and the science library, Kresge. That birthday was marked with a series of celebrations on September 21.

During the morning, open houses were held throughout the Fairchild Center, and visitors wandered through the various lab areas. Professors and graduate students were on hand to answer questions and to show off the facilities and equipment. Visitors could learn how maps are structured, what the probable causes of cancer are, and whycertain detergents get whites whiter. The second half of the day was devoted to an official birthday celebration and presentations on current research. The research represented five disciplines and highlighted the unification of all the sciences which Fairchild represents. "The purpose of the center's construction was to create more interaction between the science divisions," said Dorothea French, assistant dean of graduate studies and one of the celebration's organizers.

The history of the center's planning and construction reads somewhat like The Perils of Pauline. In its early stages, the center was rescued from one precarious situation after another, always just in the nick of time. President McLaughlin provided this background during his speech at the ceremony. In their initial plans, the Board of Trustees envisioned a "global approach to the sciences at Dartmouth." That phrase had more literal meaning than one might think: Original plans called for a science complex stretching uninterrupted from Wheeler dorm to Gilman library at the Medical School. Monetary pressures eventually pared this vision down to the more modest idea of a structure linking Steele and Wilder.

The College next faced the funding hurdle. The Kresge Foundation promised a key donation, but only if Dartmouth would commit by a certain date. On that date, the College still had not raised enough other funding to start construction. The Trustees chose to stick their collective neck out, accept the donation, and dig hard for the rest of the money. By the end of 1971 the Trustees were able to reel their neck back in. The hockey team unwittingly assisted in the effort by sacrificing a million dollars originally intended for a new rink, and a mysterious donor put the College over the hump with a final sum of money. The center was guaranteed. Almost.

In August of 1972 the center once again found itself tied to the railroad tracks. The half-acre plot on which the center would sit had originally been part of the Medical School, and the deed for this troublesome bit of ground still belonged to the state of New Hampshire. Fortunately, the College was able to thwart the potential disaster by swapping other land for the desired plot. The mysterious donor who saved the center, finally built at a cost of $5.3 million, was revealed as Sherman Fairchild, then president of the Fairchild Foundation; the center was, with much gratitude, named in his honor.

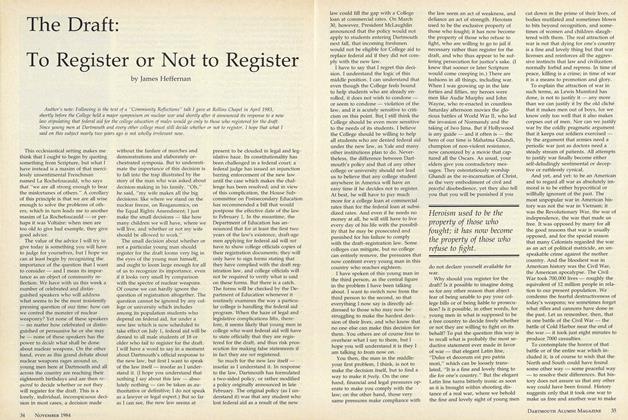

It has been ten years since the sighs of relief were heaved upon the center's completion. For those ten years, the transparent tower has structurally linked the buildings flanking it, while it has organizationally linked the diverse scientific endeavors taking place at the College. The tower is the focal point of the center. Its exterior is an appropriate foil for a major work of art on the entrance plaza. The interior, with four levels of walkways intersecting four-story-high open areas, houses a Foucault pendulum to demonstrate the earth's rotation, a geophysical globe six feet in diameter, exhibits of 18th and 19th-century scientific apparatus, and displays of mineralogy specimens.

But the tower does not merely unite the various disciplines within the sciences. Its exterior design and interior appeal charm non-scientific visitors and members of the Dartmouth community as well, The celebration of the building's, conception was accordingly lay-oriented. Hosts at the open house took care to provide examples of their work that held significance for the average person, and they explained their findings in English not always an easy task. As fourth-year graduate student Paul Morganelli pointed out, "It [his study in fluorescence] is not that difficult, it's just the terminology is another language."

The five presentations on research also took a down-to-earth approach. Bruce Pipes, associate professor of physics, spoke on the magnetic activity associated with different parts of the body. Karen Wetterhahn, associate professor of chemistry, gave a talk called "Designer Genes," on the damage done by chromium to the DNA in human cells. James Hornig, a chemistry professor and chair of the Environmental Studies Program, spoke about science's role in "the political jungle of acid rain." Laura Conkey, assistant professor of geography, gave a presentation titled, "Tree Ring Width and Density as Paleo-Environmental Tools." Finally, Gary Johnson, associate professor of earth sciences, talked about human roots in his presentation, "Developing the Chronology of Primate Evolution."

Though attended mainly by scientists, the presentations also attracted local residents, undergraduates, and visitors in town for the weekend. This mix of people exploring the sciences at Dartmouth seems likely to propel the Fairchild Center into a lively adolescence.

The six-foot-diameter geophysical globe which hangs in the central tower of the Sherman Fairchild Physical Sciences Center was one of the attractions enjoyed by visitors at the recent celebration of the center's tenth birthday.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

FeatureThe Draft: To Register or Not to Register

November 1984 By James Heffernan -

Feature

FeatureLife After the Presidency

November 1984 By Shelby Grantham -

Feature

FeatureHamming It Up

November 1984 By Gay E. Milius, Jr. '33 and Dick Dorrance '36 -

Feature

FeatureGet a Job

November 1984 By Nancy Wasserman '77 -

Feature

FeaturePractice, practice, practice

November 1984 -

Books

BooksSo Much More

November 1984 By Peter Smith

Article

-

Article

ArticleCAMPUS SQUIBS

March, 1923 -

Article

ArticleTHAYER SCHOOL ENGINEER REPORTS TO GEN. ALLENBY IN THE SUDAN

May 1925 -

Article

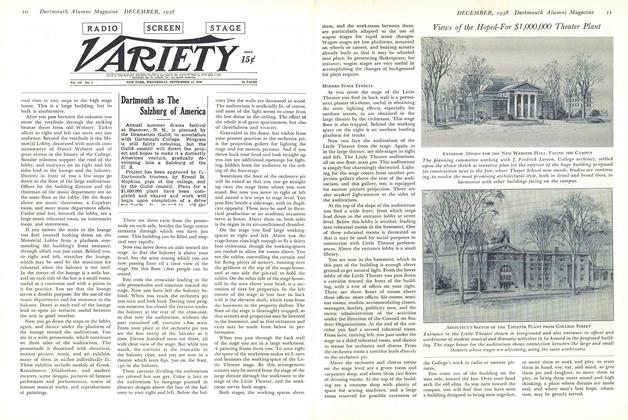

ArticleViews of the Hoped-For $1,000,000 Theater Plant

December 1938 -

Article

ArticleGive a Rouse for

SEPTEMBER 1985 -

Article

ArticleIn the Fastest Lane

NOVEMBER 1997 -

Article

ArticleFurther Mention

JANUARY 1973 By JOHN HURD '21