Harry Blunt '97 Took Lead in Architectural Planning

OUR CLASS came back to our 50th to see the new Dartmouth grown large and beautiful. Hanover has grown to the north and east and to the south, and as a village has much to be proud of in the quality of its houses and its home gardens. I want to tell my classmates something from my personal knowledge about the movement that brought about the change in our progress from the small closely knit group of buildings of our time, nearly all in sight of the campus. Those on the east and on the north sides of the campus, the old College, have great charm; those to the south of the campus are not in harmony with the spirit of the fine arts; of those to the west, only two small buildings are worth our memory—these two, the Sanborn House and the Proctor House, gave way to the needs in our time and soon thereafter. The reconstructed Sanborn room is delightful.

With all our rush and in a trying age, the land to the west of the campus was hurried into useful but not care-taking land coverage. These buildings were built at a time when the architects were not yet free from the hodgepodge that followed the great revival of expansion beginning a few years after the end of the Civil War. This was done at a time when no great school of fine arts in the architectural branch had expressed itself on college and university campuses. There was, however, a spark which set off a blaze about the begining of the century.

The little white church at Dartmouth caught the spark of the new influence before most of the colleges of the East. Stanford White, a great artist and one of the leaders of a great school of architecture, applied a touch of simple beauty to the interior of this fine old church some years before we entered college. I think this little spark was one of the earliest to be lighted in the new movement.

A few years after this Mr. McKim, a partner of Mr. White, went to the brick yards near Boston and from the refuse dump selected brick for the Johnson Gates at Harvard. This spark started the blaze which followed. The office of the great firm of McKim, Meade & White was directly across the light court from my New York office and I had a window view of him and his fellow artists, working at their drafting boards. Mr. White, in startling vigor of the great artist, stood at his board as he sketched. He was very intense while sketching. I could not see his drawings, but X could see him make them and then stand back to examine them. This was in 1903.

My firm did some work for Mr. White, and in my office were two statues of molded cement made by us for him from his design. They were two satyrs, decorative pieces made with wax mould, a new development in cement. Here in view of my window was growing a great force for the good and beautiful in architecture.

Mr. Burt L. Fenner, after he became the head of McKim, Meade & White, told me that one time Mr. McKim asked Mr. White to go and see a little church in Hanover, N. H. He said, "I think you will like it." Mr. White said, "I know that church. I did it." He had not told his partner about it. Mr. Fenner later became one of my most helpful friends. These sparks are some of the little things now hardly remembered.

The flame of good architecture was forced as though blown with a bellows; it grew at Harvard, Princeton, and Yale, spreading simultaneously to other colleges and universities. Some of the western universities went ahead of the conservative east. The University of Minnesota was one.

Dartmouth was struggling with little guidance in growing up. Let's think of the earlier trials and tribulations, when we built Bartlett and Wilson Halls, and later Fayerweather, not as bad as they could be, not as bad as we did at our time in the unfortunate, yellow brick Butterfield, which was torn down after the new revival about 30 years later.

Rollins Chapel is low and well-covered by trees. But the great Richardson who built Trinity in Boston would not have felt complimented had he seen it. Few if any of the great architects who followed Richardson caught his spirit. Rollins Chapel speaks, not with its low rounded stone arches or its red interior woodwork, but with the memory of its greatest speaker, Dr. Tucker.

There came a change in Dartmouth College, as great a change as at Harvard, Yale or Princeton—a very sudden change. Many able men have helped to create this new Dartmouth. One of our classmates was the most outstanding to bring us, as a college, up on our feet and to start us off in the direction of the new, fine wonderful architectural college of today—RßY BLUNT.

The night before Harry went to his first meeting, as a newly elected trustee, he and I talked about the College of the future, the college to the north and to the northwest. Long into the night we talked about the College and good architecture and good architects.

Harry had just finished a beautiful home which X loved. I had just finished guiding the building of 1380 homes designed by masterful architects. We talked that night about experiences with these men. We unburdened our hearts to each other about the bad things that we could see in the evening light, sitting on the porch of the Inn. I never prayed so hard in my ife, as I did that night, that Harry Blunt might do something about it.

The next day Harry went to his first meeting. He told me about it afterwards. What he said at that trustees meeting resulted in his being appointed to the leadership of the building program. He and I talked a lot after this appointment and we corresponded at length about the selection of professional leaders to start the new Dartmouth, and many details of starting a program and about a plan.

These letters are a great source of joy to me now as I re-read them. I quote only a few excerpts from these many letters.

From Harry's letter, July 5, 1921: "My dear Bill: Thank you for your letter of the 27th, and I look forward to your further letter and plan in detail to compare with some of our own ideas and incorporate as much as possible into them.

"Coming back to Nashua I checked up some of my previous opinions to you, and if it is possible for us to connect with the architect, Pope, my feeling is that he is just exactly the person necessary for the development there. What his attitude toward a more or less unremunerative job would be, I do not know.

"There is no doubt that the question of the architectural development of the College has been in the air and been severely criticized, and I am glad that you and I are both in agreement as to its necessity. I want very much to be able to call on you, later, to your fullest extent in giving your most valuable criticism to the ideas that may be worked out."

I quote from a letter from Burt L. Fenner, July 14, 1921, and sent forward to Harry Blunt as soon as received: "Dr. Mr. Ham: I have your letter of the 13th instant. The architect to whom you refer is undoubtedly John Russell Pope. Mr. Pope is, without question, one of the very able men in our pro fession. He has had long experience with work of importance, and you need have no hesitation in o-iving him the highest possible recommendation."

A long-hand letter on yellow note paper from "Hiram" Tuttle reads: ''Six hours short of Monroe, La.—Hot and June 25 Dear Bill:—"Was in Hanover for part of Sunday and for the first time got the new development plan into my head. Have just written Blunt telling him how much beauty has been added for all time. I said to him that you were the first one I heard mention the need of a plan of development. I think the plan is done because you saw the need. I think we all owe you gratitude." This letter is not dated but was written after progress had been made.

Two paragraphs from a recent letter to me, dated Jan. 26, 1948, from Otto R. Eggers, who was associated with the late Mr. Pope: "I want to thank you for your interesting letter of Jan. 10, 1948, recalling to our minds the very pleasant relations which Mr. Higgins and I had during the study and final production of the plans and illustrations for the future development of Dartmouth College.

"Mr. Blunt, with his foundational interest in the history and traditions of Dartmouth, felt that these factors should be reflected in the architecture and character of the proposed future buildings. This was the basic thought that led to Mr. Blunt's suggestion to call in Mr. Pope as consultant for this very important project."

From Daniel P. Higgins, another associate, who wrote to me on Jan. 30, 1948: "I was very much interested in reading the exchange of correspondence between yourself and Mr. Eggers, relating to your interest in the architectural program for Dartmouth College, and Mr. Blunt's deep interest. "Your letter took me back to the very happy

memories of our relationship with Mr. Blunt, who was outstandingly enthusiastic about the future development of Dartmouth.

"It is very pleasing to us to note that Mr. Blunt is to be given this recognition which you are preparing, because we feel that it was his leadership which made possible some of the meritorious achievements now at Dartmouth."

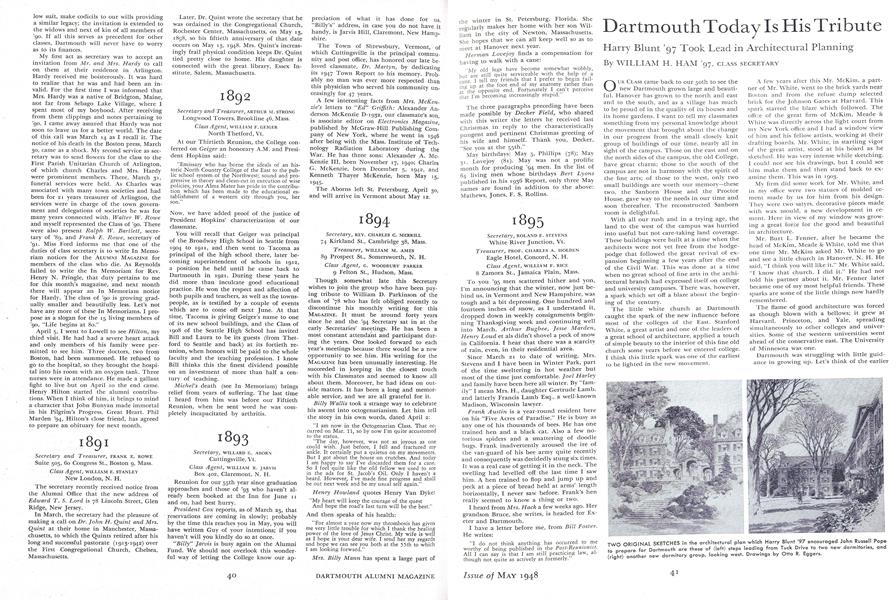

I have assembled photographs of the original sketches made at the time Harry Blunt was working out a program. These are historic in the development of the new Dartmouth. Some of them accompany this article. All of them are on file at the library.

I think the long study of the careful preparation of many beautiful drawings of various proposed buildings crystalized the ideas of many people who had looked forward to the larger college, and that the devotion which Harry gave to his task has resulted in stamping the college with his vision.

"Hitchcock Field" became the west axis in his dreams. Beautiful drawings are often epoch making and in the case of the College to the north and to the west of the campus Harry Blunt's dream has come true.

One of our classmates had the honor to tell Harry shortly before his death how much beauty has been added for all time.

I am most happy that I was able to help a little and to come to know him and to feel his personal charm during these short two years while he was working for the College. To me he seemed inspired.

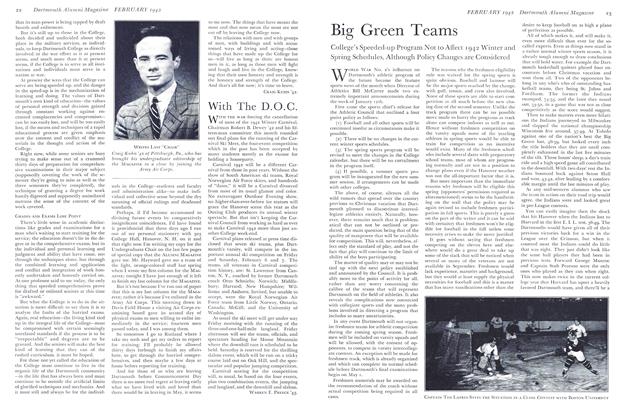

One picture of Russell Sage Dormitory, so outstanding in its simplicity and so delightfully fenestrated, is included. It was the only building completed before Harry Blunt died.

The contemporary correspondence shows that the program was being planned for a long time and that other and younger architects would be expected to carry on, and this of course has taken place. The mam theme Harry and I talked about and wrote about and agreed upon was to have an architectural plan of the College, and to have the College guided by superior architectural talent whichhas been accomplished.

Harry Blunt was an artist at heart, and Ifeel sure had he lived that he would approvethe feeling of Dartmouth College today.

I quote this statement of President Hopkinsfrom the ALUMNI MAGAZINE, January 1924,shortly after Harry's death:

"In his devotion to college needs, his indefatigable zeal within the range of his own interest, and his broadminded acceptance of policies into favor of which he did not come instinctively, he has been tremendously helpful to the College, and has rendered service that probably no other man in our group could have done."

I also quote statements by Thomas Dreierfrom the ALUMNI MACAZINE, January 1934: "If he could have his way, Dartmouth would have the most beautiful plant in the country. He believed that boys, no matter how much like young animals they may act. at times, are influenced by beauty.

"He was the sort of Dartmouth man who made those of us who are not Dartmouth men wish to goodness we might boast as he boasted of the Dartmouth of today and could dream as he dreamed of the Dartmouth of tomorrow."

'97, CLASS SECRETARY

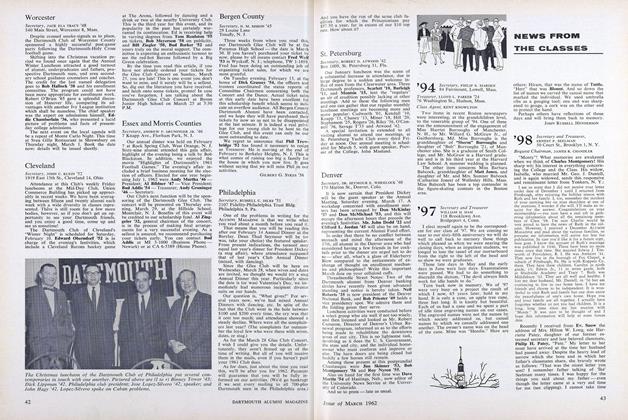

TWO ORIGINAL SKETCHES in the architectural plan which Harry Blunt '97 encouraged John Russell Pops to prepare for Dartmouth are these of (left) steps leading from Tuck Drive to two new dormitories, and (right) another new dormitory group, looking west. Drawings by Otto R. Eggers.

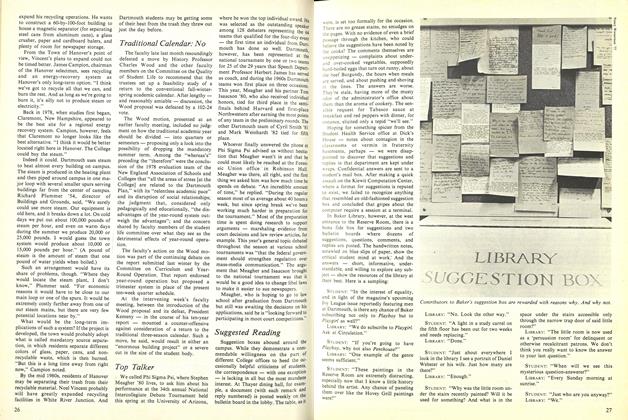

THE FEEL OF MODERN DARTMOUTH, although not the actual architectural form, is in these pre- hmmary drawings prepared in 1922-23 by the firm of John Russell Pope, at the instigation of Trustee Harry Blunt 97. The sketches, by Otto R. Eggers, associate of Mr. Pope, show (top) the proposed library, (center) the remodeled Inn, and (bottom) College Street and a new cross axis.

RUSSELL SAGE HALL, "so outstanding in its simplicity and so delightfully fenestrated," was completed before Harry Blunt died in 1923.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Article

ArticleTHE MEANING OF TOLERANCE

May 1948 By W. K. JORDAN -

Class Notes

Class Notes1918

May 1948 By ERNEST H. EARLEY, DONALD L. BARR, DAVID L. GARRATT -

Class Notes

Class Notes1919

May 1948 By J. K. HUNTINGTON, MAX A. NORTON, ROSCOE A. HAYES -

Class Notes

Class Notes1942

May 1948 By JAMES L. FARLEY, JOHN H. HARRIMAN, ADDISON L. WINSHIP II -

Article

Article"Pest House" Days

May 1948 By ALICE POLLARD -

Class Notes

Class Notes1924

May 1948 By JAMES T. WHITE, RICHARD A. HENRY, DONALD E. COYLE

WILLIAM H. HAM

-

Class Notes

Class Notes1897

October 1948 By WILLIAM H. HAM -

Class Notes

Class Notes1897

December 1948 By WILLIAM H. HAM -

Class Notes

Class Notes1897

February 1956 By WILLIAM H. HAM -

Class Notes

Class Notes1897

February 1958 By WILLIAM H. HAM -

Class Notes

Class Notes1897

March 1962 By WILLIAM H. HAM, JOHN RUSSELL HENDERSON -

Class Notes

Class Notes1897

May 1949 By WILLIAM H. HAM, MORTON C. TUTTLE