When it seemed best for me to leave Boston in 1899 because New York was calling, I quit the Pinkney St. Gang with a heavy heart. My new job was with the firm of Waring, Chapman and Farquhar. Colonel Waring and his associates had blazed a trail in the new field of sanitary engineering with such daring that it became epochal. The big cities were just beginning to struggle seriously with the bath water and also city filth. The small cities lived along with no sanitation and little street cleaning. All of the large cities were in trouble.

Boston solved its problem by building big sewers and turning the effluence into the harbor. New York built little sewers and dumped the sewage into both rivers. Chicago for quite awhile after the advent of the bath tub dumped the city sewage into Lake Michigan, its source of drinking water, and later dug a ditch from the Lake to the Mississippi River Valley, thus passing on its filth to St. Louis, Memphis, New Orleans and other cities.

The large estates on Long Island and around the Shrewsberry River in New Jersey and up the Hudson were in trouble with their private sanitary jobs. One place on Long Island had 13 bathrooms. New York City with its filthy streets needed professional advice but, more than advice, the will to clean up. In most of these problems Col. Waring and his firm had a hand. One summer before and the summer after I graduated from the Thayer School I did accurate surveying on town and state line work in Massachusetts and Rhode Island. This surveying was helpful to me in my new job.

The problem was new and untaught in the books of the engineering schools. The hydraulics of sewerage and the fundamentals of breaking down the nitrogenous matter into its harmless elements was all new and known only to a few engineers. We were working ahead of the textbooks. Allen Hazen, one of the great engineers of all time, a graduate of the Thayer School, was struggling withwater pollution for the elimination of typhoid. He used largely in his work the slow land filter. I built one for him near Yonkers. Fuller and others used a mechanical filter for t(ie same purpose. Sewage had caused the trouble and the bath tub was the villain because of the large increase in the use of water«hen people began to bathe instead of washing themselves.

Hanover washed and didn't bathe until our sophomore year The first water from the reser„nir was so bad smelling that it could not be ~«d and the old pump at the well on the campus where old "Pat," the vagabond poet songster, mming home from Lebanon, entertained ]ohnMeserve, Herby Thyng, Hiram T tittle, Georgelewis and me with his "Grafton County Jail Song " was still the college water system.

The latrine in Reed Hall, the subject of a song written by Judge Sibley, was paralleled with the sanitary urges all over the east and the south and I guess the west also. I was soon given a good transit and a lot of plans and told to solve sanitation for a lot of big estates on Long Island, down the Jersey Shore, up the Hudson and on the outskirts of Pittsburgh and later to help with the elimination of the sewage problem for the village of Stockbridge, Mass., a job which was many vears ahead of the engineering of that day During this time I kept a hang-out in New York to use weekends and between jobs. My first New York City home (?) was on "West 21st St. between 9th and West Ave. in the Chelsea section, a run-down brick and brownstone area north of the warehouse district, east of and near the docks, south of the slaughter house section called "Hell's Kitchen" and west of the Tenderloin with its beer joints, red-lights and sin. I walked to my office at 18th St> and Broadway, stepping over dead cats, around piles of ashes and rubbish dumped by the slew-foot, scavengers onto the sidewalks, frequently stepping out to avoid these rubbish piles into the street cluttered with horse manure. "West Ave. with its heavy trucking furnished a smell for all of the area. (Kipling tells of remembering places by the smell). I certainly remember West 21st St. as he did his eastern world. t

My brother Tom and Lindley Palmer of '96 let me have a bed with a hard mattress with one straight back chair and a hook on the wall. There were no closets. The room was the full size of the house, about 18 x 30, with one gas jet pn one wall, our only light for reading. This dim illumination about the candle power of an oil lantern—meant three chairs in a-half circle with the light coming over the shoulder. One night the bright eyes of youth could not read the evening paper and we overhauled the gas jet to find a wad of cotton underneath the tip to economize.

Grub was limited and at the bell we three ran down the three flights to a dark basement dining room. Speed was important for the first helping was more generous. This cheap boarding house run by an old-maid of the Victorian era had one pleasant feature. From the front high steps we could look across to the green lawn of the Theological Seminary on the other side of the street directly opposite.

As I came directly here from Boston, I wore a derby hat and a sack coat and carried a green baize bag for njy papers until I caught on to the style set by the Hall Room Boys uptown, among these being Herby Thyng, and Gibson of our class and Hapgood of '96. It didn't take long—my first Prince Albert coat was made by a tailor who worked for Browning King and it was much like Dr. Bartlett's except longer and flared a little. The coat, high hat, striped trousers, shiny shoes with spats, ascot tie with horse shoe pin, and a cane let me join the Easter Parade just like Gibby, Herby and Hapgood and other Dartmouth Pals. Soon to my evening tails I added an opera hat—important to the atmosphere of the third halcony of the old opera house (seats $1.00) some high-brows called these seats "nigger heaven."

New York at the turn of the century was conspicuous with its political manipulations and at that time the wherewithal for the politicians came very largely from the brewers. New York was a beer town. The brewers paid generously and had their big show-off with stylish brewery wagons with big beautiful horses with harnesses gleaming, driven by husky drivers. The Tenderloin was a large area of bright lights, music and a number of night clubs of the period far different from the present expensive set-ups a large number of dance halls—one conspicuous one called the "Old Hay Market" was fairly near the center of the district. The Tenderloin was a place for New York visitors to go and be entertained-A few of the lower-class places used knock-out drops to help relieve visitors from out-of-town of a fat purse, but by and large the whole area was safe and tempting to its visitors. One beer joint was known as the "Pump" on 27th St. near 7th Ave., the old headquarters of the then Police Chief, who aspired to be a statesman and ran for Mayor against Seth Low. It was here at the "pump" that the "New Deal" was started. Here this Chief of Police coined the phrase which is and has been the heart blood of the "New Deal" in the short, straight out-spoken New York tough language—"the down-trod shall be uplift and have their say."

The political wherewithal changed from beer and women to another source of income very soon after I went to New York. This change came by two great steps—the first one was the introduction of Portland Cement as a new building product (I used Rosedale Cement in my earliest work). Cement became king to the boom in building subways, street paving and the tunnels under the rivers. This new giant in construction looked like and became big business to the politician. The cement industry itself was free from political graft, but all through the uses of concrete the tribute was evident. Another big step was the change in the high spots from beer to cocktails and highballs. These two elements plus a little effort by the law and order societies gradually closed the Tenderloin beer parlors, and big graft went high hat and soon only a few streets like 34th and 42nd had the gaily dressed night With the building of apartments, the Tenderloin with its red lights was closing its doors and scattering its sin.

New York showed me at the beginning of the century its many sides, and in my early stay there I am glad that I saw lots of the fine things of the great city.

A visit to Schribner's Bookstore one day gave me a picture which stands out very vividly in my memory. "Gibby" greeted me among the beautiful volumes, always a temptation to me. and pointed out to me a customer none other than Teddy Roosevelt. I watched him pick up a book, run through it rapidly and throw it down on the counter with one word of comment, "rubbish." Gibson loved books and here he had a chance to pick and choose many first editions which are now in the Baker Library at Dartmouth—his gift to the College. Some of these books were bought by him in his early days after college when he had a limited income. I know no truer gift from the heart to the college than these numerous volumes.

New York, the most fabulous city of them all, is changed. Has always been changing. This little picture is a memory painting of the small part of the big city that I knew when I was young and had a good time on a small income.

With the upheaval in politics when Seth Low, formerly president of Columbia, came into power, the efforts to carry out the program organized by Col. Waring and his associates to clean up the city were very evident. This great army of misfits, now dressed in their white suits and white_ hats with wheel push cans and brooms, changed it all from a rubbishy, dirty, smelly city so that the great avenues and many of the cross streets began to shine due to Col. Waring's "White Wings" of New York. The city was changing from gas lights to electricity and from horses to motors and the jangling bell of the horse car and the frightening speed of the cable grip car going around the curves all changed and very suddenly. The lower East Side with its many nationalities was always interesting to me. Harlem was the home of the well-to-do people who lived comfortably in their brownstone houses.

The papers of this time carried many cartoons of the Hall Room Boys and, as one of them, I claim that Ward McAllister would never have been able to establish his New York styles if it had not been for the country and small city boys who came to New York and lived in the small rooms of the boarding houses, dressing up and showing off at the Easter Parade, and at the opera and elsewhere. As I look back now, among my acquaintances in this great group of young newcomers to New York, quite a good many of them are now presidents of big companies or high up in financial circles. Most of these men were college graduates about our time, and they found New York a marvelous place for starting to climb the ladder and having an interesting life in the days when money had to go far.

Secretary and Treasurer

886 Main St., Bridgeport 3, Conn.

Class Agent, 862 Park Sq. Bldg., Boston 16, Mass.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Article

ArticleMusic at Dartmouth

June 1949 By ANDREW L. PINCUS '51 -

Class Notes

Class Notes1918

June 1949 By ERNEST H. EARLEY, DONALD L. BARR, RICHARD A. HOLTON -

Article

ArticleSalmon P. Chase

June 1949 By EDWARD C. LATHEM '51 -

Class Notes

Class Notes1937

June 1949 By ROBERT C. BANKART, ARTHUR H. RUGGLES JR., ALAN W. BRYANT -

Class Notes

Class Notes1926

June 1949 By E. PAUL VENNEMAN, HERBERT F. DARLING, ALBERT E. M. LOUER -

Article

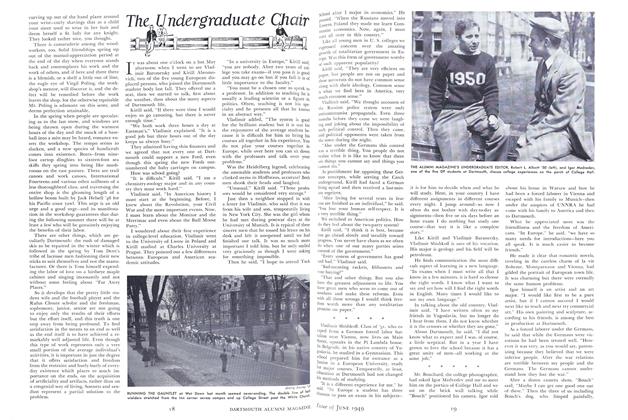

ArticleThe Undergraduate Chair

June 1949 By Robert L. Allcott '50

MORTON C. TUTTLE

-

Class Notes

Class NotesClass of 1897

August, 1926 By Morton C. Tuttle -

Class Notes

Class NotesClass of 1897

MARCH, 1927 By Morton C. Tuttle -

Class Notes

Class NotesClass of 1897

DECEMBER 1927 By Morton C. Tuttle -

Class Notes

Class NotesCLASS OF 1897

NOVEMBER 1929 By Morton C. Tuttle -

Class Notes

Class Notes1897

April 1943 By WELD A. ROLLINS, MORTON C. TUTTLE -

Class Notes

Class Notes1897

May 1949 By WILLIAM H. HAM, MORTON C. TUTTLE

WILLIAM H. HAM

-

Class Notes

Class Notes1897

January 1950 By WILLIAM H. HAM -

Class Notes

Class Notes1897

November 1953 By WILLIAM H. HAM -

Class Notes

Class Notes1897

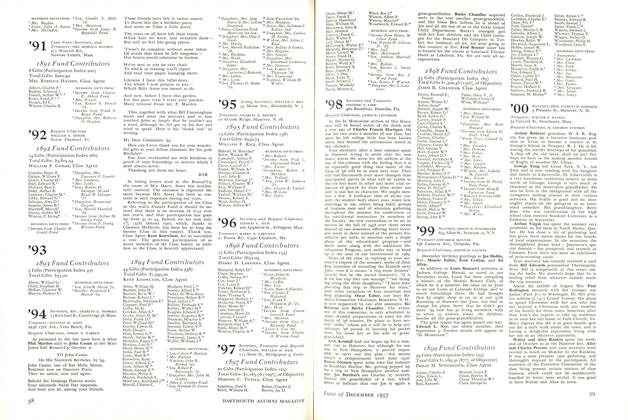

December 1957 By WILLIAM H. HAM -

Class Notes

Class Notes1897

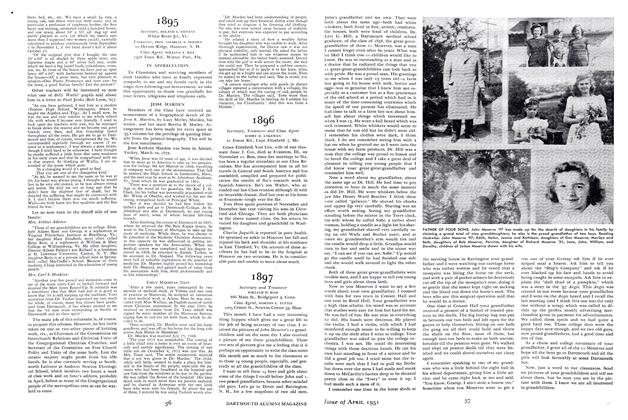

April 1951 By WILLIAM H. HAM, MORTON C. TUTTLE -

Class Notes

Class Notes1897

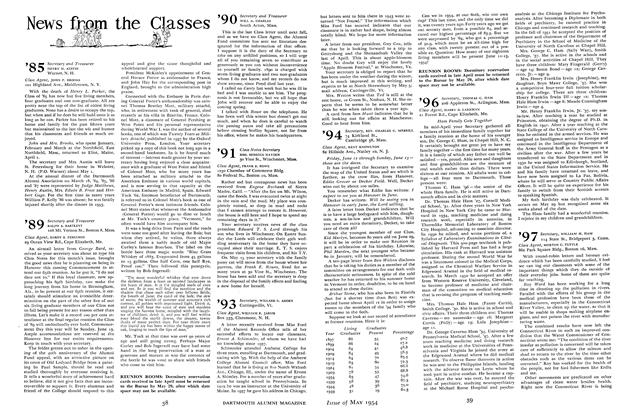

May 1954 By WILLIAM H. HAM, MORTON C. TUTTLE -

Class Notes

Class Notes1897

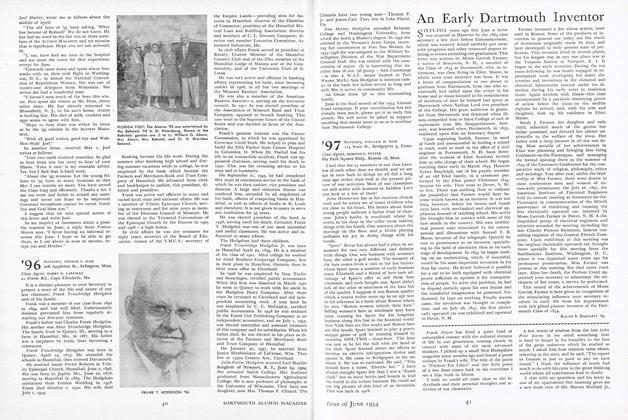

June 1954 By WILLIAM H. HAM, MORTON C. TUTTLE

Class Notes

-

Class Notes

Class Notes1989

December 1990 By Carrie Luft -

Class Notes

Class Notes1941

May/June 2002 By Dick Jachens -

Class Notes

Class NotesClass of 1889

February 1937 By Dr. David N. Blakely -

Class Notes

Class Notes1952

JUNE 2000 By Henry W. Williams Jr. -

Class Notes

Class Notes1910

April 1956 By RUSSELL D. MEREDITH, ANDREW J. SCARLETT -

Class Notes

Class NotesChicago Association

May 1935 By Whitney Campbell '25