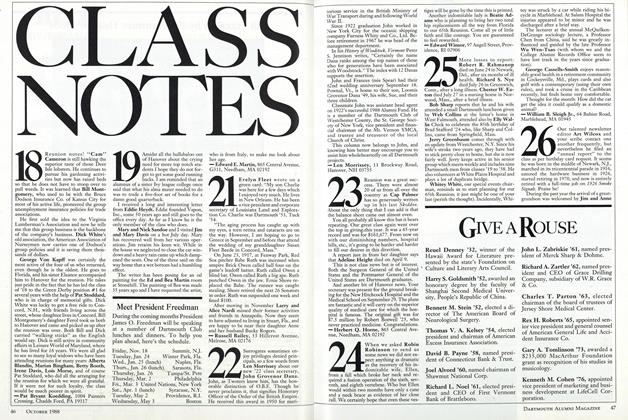

Fifty years ago, at ten o'clock in the evening of May 13th, fire broke out in the basement of the old White Church, and within a little more than an hour all that was left standing was the chimney. "The suddenness with which the fire struck and the rapidity with which it moved left people stunned and hardly aware of the fact that one of the last of the old landmarks was gone," the ALUMNI MAGAZINE reported.

The Church of Christ at Dartmouth College, the meeting house that replaced Eleazar Wheelock's crude chapel, stood for 135 years opposite the northwest corner of the Green. The steel-beam sculpture "X-Delta," presently gracing the front lawn of Sanborn Library, is situated about where the main entrance was. President John Wheelock had drummed up a community subscription of 355,000, paid in cash, agricultural products, lumber, and labor (at the rate of 58 cents a day), to begin construction in 1794. His church turned out to be the seat of a far-reaching parish squabble that soon divided the town, the College, and the Board of Trustees, whose vote to remove the president eventually resulted in Daniel Webster arguing . the Dartmouth College Case before the U.S. Supreme Court.

Not only was the church the oldest public building in town, but for more than a century it also provided Dartmouth and Hanover with the only adequate auditorium. Lectures, concerts, "entertainments," and also commencements for some 6,000 seniors were held there. The list of famous speakers who stood behind the pulpit includes Webster, Rufus Choate, Oliver Wendell Holmes, Levi Woodbury, Ralph Waldo Emerson, Edward Everett Hale, Matthew Arnold, Walt Whitman, and D. L. Moody. Mourning the disappearance of "more than a landmark," Sidney Hayward "26, editor of the ALUMNI MAGAZINE and secretary of the College, suggested it would be well to mark the spot where the building had stood, "for in more than one sense it may be regarded as holy ground."

E. J. "Bubby" Bartlett, professor of chemistry from 1879 to 1920, citing a reference to the church as "the Lord's barn," was less reverent in his recollections of the old structure. "The building itself, though a modernized relic, was never dear to me," he wrote a month after it burned. "Perhaps that was because I could never erase from my mind the memory of that primitive and unadorned place of worship which nearly to the end of my undergraduate days I was compelled to attend twice every Sunday. ... The enlarged and beautified form of the audience room from the plans of Stanford White never completely removed recollection of that old bare place, with the two little stoves at the south end drooling on the unprotected worshippers below creosote from the smoke pipes running under the galleries to the chimneys at the north end. In those early days, the choir was safely placed in the south gallery where nothing could be thrown at them, but able, in the words of one of the preachers, 'to make a disturbance there as well as anywhere.' "

When the fire was discovered, flames had broken out of the rear wall and smoke was escaping from the roof. Before long, smoke appeared in the belfry as the fire spread to the attic. Ten minutes after the alarm was sounded the fire department was at work on the back of the building and a well-organized crew of students was marching in and out of the main auditorium, which wasn't yet affected, removing the furnishings. Suddenly the roof was in flames. Not long after it collapsed, along with hopes that the building could be saved. The firemen turned their attention to preserving the vestry and to protecting nearby Sanborn House.

Whoever reported on the event for the ALUMNI MAGAZINE provided a stirring account of the conflagration: "In death, the old church was dignified and stern. Streams of water played futilely upon its ancient timbers aflame with fire which sent clouds of sparks high toward the sky and beat back the throng of onlookers below. Its belfry and its whole frame burned almost to a crisp before a single beam gave way. Defying all laws of God and man two uprights running from the ground to the top of the steeple clung solidly to the position they had held since 1795. The roof fell in, the walls toppled over, but those two flaming timbers stood as though rooted to the spot. At last they swayed perilously, and disregarding the ruin about them, slowly and majestically curved toward the ground."

The undergraduate editor, W. E. Ferry '32, with an eye for more mundane details, reported seeing "an informal betting ring offering odds that the chimney would stand, that the west wall would fall eastward, that the east wall would fall westward, and finally, that the flaming belfry contained no bell." He also noted the arrival of an ice-cream vendor.

The White Church lighted the night sky May 13, 1931, burning to the ground in an hour.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

FeatureTenure: an academic necessity

April 1981 By A. E. DeMaggio -

Feature

FeatureQuestion: Who are the Arts for and, Indeed, Who Owns Dartmouth?

April 1981 By Peter Smith -

Feature

FeatureTenure: the tragedy of the slaughterhouse

April 1981 By Peter W. Travis -

Cover Story

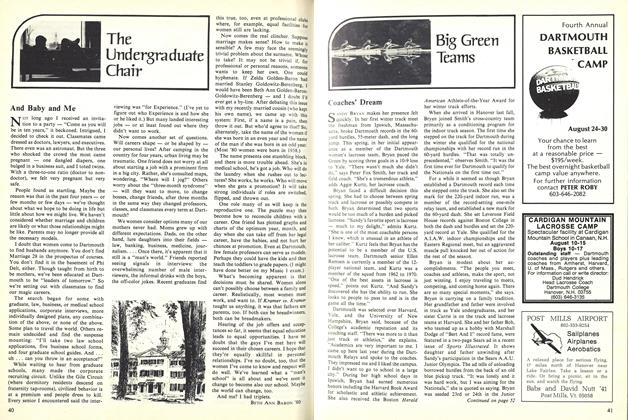

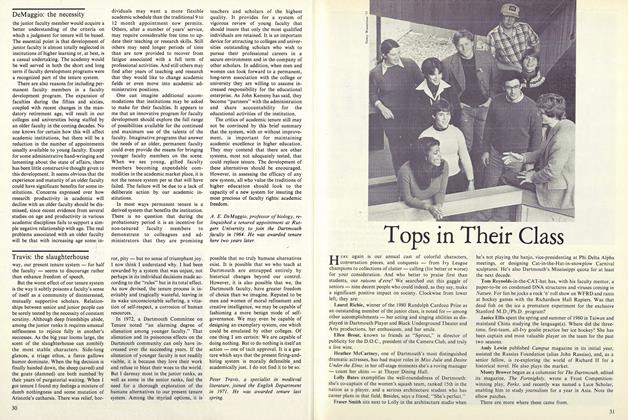

Cover StoryTops in Their Class

April 1981 -

Cover Story

Cover StoryChargé d'Affaires

April 1981 -

Cover Story

Cover StoryBeethoventorte

April 1981