The Second in the Series of Reports By Dartmouth Men Around the World

AS WINTER DESCENDS On Paris the French people like everyone else today, are faced with an increasing number of domestic and international problems. They are suffering through the worldwide issues in much the same way as the American people except for the very pertinent fact that the French, as always, are plunk in the middle of everything. This alone is enough to explain the fact that one cannot be French or even reside in France and at the same time be an optimist. It hardly needs repeating that the French have been sitting in the middle for so long that the thought and fear of war are forever with them and it will be a long time, indeed, before this state of mind can ever be changed. When it is, the world will really be safe at last.

As much as the French worry over the far-reaching effects of international events, domestic issues quite understandably outweigh the international in the French press. The series of cabinet crises this past summer and the rapidly rising cost of living have brought renewed and vigorous, although sporadic, strikes on the part of the Communist labor union, many of which have been joined, however reluctantly, by the non-Communist Christian union. The fact remains that the French would rather eat and eat well—than anything else. With many scarce and necessary items still rationed and with the price of meat really prohibitive for a great part of the population, the "unrest of the French is understandable.

Most recently the government has begun to meet some of labor's demands, notably by turning the other way as bakers sell bread ration free and by organizing strongarm squads to determine that meat is sold only at government levels. All this is designed, quite naturally, to restore the faith of the laboring class in an increasingly shaky government. However, at this writing, the government has not been able to meet labor's demands for higher wages simply because the money is not in the treasury and, for this reason, rates have recently been increased for gas, electricity, coal and transportation, all of which are government owned. Even so, the government will be left with a very enormous deficit on its hands this year.

The unstable character of the French government has been due in part to its set-up which consists of so many parties that, being unable to agree among themselves, no one party can ever obtain a majority. Since the liberation France has been governed by a series of coalition governments, all designed to keep both De Gaulle and the Communists from power and all totally unable to consolidate their own. during the summer months when it seemed that cabinet followed cabinet within a matter of days, there was a renewed call for general elections by De Gaulle who would, of course, probably profit most by them. De Gaulle has a tremendous following, but the average French citizen is not sure whether his ideas, which call for a strong central figure with virtual dictatorial powers, would be good or not. But it seems to be increasingly apparent that an iron-clad rule is one of the very few things that may be able to put France back on her feet. However, the matter of elections is very much up in the air, to say the least, for the only way these new elections can be brought about is to dissolve the present assembly and no one believes that the present deputies will want to vote themselves out of their jobs. Even this procedure, many authorities say, is unconstitutional. If any elections are held in the fairly near future it would certainly mean a direct showdown between the Gaullists and the Communists, with no little blood shed and even the possibility of some kind of civil war.

Despite their primary preoccupation with domestic affairs, the French are intensely interested in the United Nations, the more so because of its location in Paris during the current session. The French have a good deal of faith that the UN may be able to settle peacefully the problems now besetting the world and, in this respect, they are more patient than most. But the French are generally convinced of another world struggle, this time of course with Russia and, in that eventuality, they become rather panic-stricken at the thought of the number of Communists in their country. The French press, too, is generally more patient with UN proceedings than that of most other countries, but there is a slight feeling that there is perhaps too much talk and not enough concrete action. The French, however, look upon the international area around the Palais de Chaillot with something approaching mystic awe: they are first impressed by the immense gathering of world diplomats. To date, the French have been most fascinated by the antics of Americanborn Garry Davis who renounced his citizenship, became a self-styled "citizen of the world" and camped on the UN's doorstep. He received a great deal of bewildered attention in the French press, but after being allowed an additional three months in the country he has discreetly disappeared.

Aid from the Marshall Plan is already evident in some phases of everyday life, especially in the color and texture of the bread which has lightened considerably even since my arrival in March. Aided by a bumper harvest here this year this should do a great deal to boost the morale of the French who, I am sure, eat and enjoy bread more than any other people. The current bread is considerably better than that made from American corn flour which was shipped here following the liberation and about which the French are most bitter. There are increasing numbers of American products in the stores and in the country bags of white flour are not an uncommon sight. There is a slight degree of increasing farm mechanization, although oxen still very heavily outweigh tractors. But it is sadly true that the French are rather miserably informed about the extent of the aid given to them under the Marshall Plan, the Communist Press being the only one to feature it extensively and then, of course, only to attack it. The general impression is prevalent among most French people that the money and products they are now receiving will have to be paid back dollar for dollar and piece for piece before accounts are settled. In attacking the Marshall Plan, the Communist press has at least made the population understand the Plan's purpose.

The French continue to think of Americans as somewhat cockeyed and impetuous and American acts no longer evoke too much surprise. The French have even gone so far as to nickname one of their loonier criminals, Roger I'Americain. There is an almost complete misunderstanding of American life, fostered by the fact that the French press continues to play up only our most bizarre side. The Communist accounts, of course, are mammothly distorted and as their papers have a stout circulation even among non-party members, most people here have the impression that we are perhaps as crazy as any race can get. One of the more recent features here has been the appearance in the French press of a story about a nude young woman who appeared on the Senate office building in Washington and this has been played for all it was worth. The French typically headlined it: "Victim Of The American Cold War."

Virtually all of the Paris papers carry stories in this vein, most of them being constructed along the lines of the New YorkNews: vari-colored type; large, splashy headlines; and good, juicy stories of lus. and violence. Only the staid and excellent Le Monde approaches the conservatism of The New York Times, and the Communist L'Humanite is filled with such absurd exaggerations that it hurts to think of people swallowing them. Due in great part to these newspaper accounts, the French are totally unable to understand us. They stand in awe of our refrigerators, central heating and modern kitchen appliances and mutter that "you have everything": they practically stand on their heads in disbelief when shown pictures from a publication like Life. But despite the fact that our modern conveniences are far too expensive for most classes of French society, even if they could be purchased, the general run of the population would probably never go so far. What was good enough for Napoleon and for their grandfathers is good enough for them and, for this reason, they sit in chairs in which no human form could possibly be comfortable, buy their meat every day and keep it in ventilated closets and live generally in strictness and formality. Despite the economic factor, it is almost certain that they would not bother to improve this kind of living, even given the opportunity.

Regardless of the numerous and perplexing problems besetting the world, Paris is still as gay and exciting a city as one can find anywhere in the world. From the outside it would be difficult to imagine that anything unusual was happening. To be sure, prices here are enormously high for the working class and, for that matter, for just about every class of French society, but Paris is still a veritable pleasure grove for the well-heeled tourist, equipped with one or another of the hard currencies: dollars, Swiss francs or Portuguese escudos. Although the free market rate for the dollar hovers around 310, the black market offers as much as 475 and at that rate life here is reasonable, to say the least. Stores are stocked with practically everything one could want, the only trouble being that they are far beyond the reach of the French purchaser. There are fine leather goods, traditional handmade lingerie, fascinating antiques and other goods of this sort which appeal to the tourist and which the tourist alone keeps on the market.

Paris is still a first-rate cultural center and virtually all attractions play to booming crowds. Theatres are excellent and well attended. There are two versions of the Comedie Francaise presenting classical French drama, and in other parts of the city one may see the celebrated actors Louis Jouvet, Jean-Louis Barrault and Sascha Guitry who, despite a somewhat dubious record during the occupation, is nevertheless generally well received. The Opera is State-run and quite poor in voice quality compared with the Met, but the sets are fastidious and beautifully fashioned. It is well worth the price of admission (about 75 cents for a good seat) just to get inside Garnier's Opera House which is in the best 19th century tradition of gilt, chandeliers and curving staircases. There are several orchestras in Paris of excellent calibre and a first-rate musical season which offers such luminaries as Isaac Stern, Menhuin and Rubinstein, to mention but a few.

The Sorbonne is currently attended by close to two hundred ex-G.l.'s and many thousand French of all varieties and both sexes. The educational set-up, at least for advanced degrees, is such that all the initiative is on the part of the student. Once registered at the university, the advanced student need not attend any classes if he so desires. That is, the student is left to choose the lectures he desires to attend and there is no formal enrollment for them and no attendance taken. The university is also largely supported by the State and the tuition fee is about 1,000 francs a year ($2.50 at the current rate of exchange), a sum which seems quite ri- diculous compared with tuition fees at home. G.I. students with their subsistence allotments in dollars are able to live well, if modestly, and their monthly pay is often more than that of their professors. The greater part of the students are immensely earnest and the instruction is excellent. The American students here are not unlike those at Dartmouth, at least in dress, for plaid shirts and baggy trousers are much in evidence. There is quite a tendency to grow beards of all descriptions but, as I remember, this has no counterpart in Hanover. There is a great deal of lounging about cafes, especially those on the Boulevards St. Michel and St. Germain near the university, not unlike Dartmouth students at the Hanover Inn Coffee Shop, although here it is a much more serious pastime.

The students are quite rabid about pol itics and not a few of them, rather pathetically poverty stricken, are avowed Communists. There are a few Communist clubs and others set up by the French, Britis and Americans which act as a sort of anticominform bloc. The bulletin boards are covered with their posters: merely another example of the East-West struggle in progress the world over. But on the outside, life in Paris continues to be gay and spirited; Paris continues to be a very great cultural center and she continues in a desperate attempt to recover her poise and be once again, fully, the city of the song writer's dream.

A small anecdote in closing may serve to illustrate the temper of French life today. When my wife and I first arrived here in March we lived in a small hotel on the left bank of the Seine. It was quite an unassuming structure and like most such establishments the bathroom was down the hall from our room. The first thing one noticed on entering the bathroom was a conveniently located stack of old copies of the morning paper Le Figaro. This, I suppose, indicates the present-day fate of French conservatism.

THE AUTHOR: William i. Zeitung '43 in Paris, where he is studying at the Sorbonne as recipient of a Research Foundation fellowship in fine arts. An honors graduate of Dartmouth, he got his M.A. at Columbia last year after serving three and a half years in the Army Air Corps. He was married last fall and plans to teach fine arts upon his return.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Article

ArticleCancer Pain Reduced Through His Research

December 1948 By JOHN HURD '21 -

Article

ArticleDeaths

December 1948 -

Class Notes

Class Notes1918

December 1948 By ERNEST H. EARLEY, DONALD L. BARR, DAVID L. GARRATT -

Class Notes

Class Notes1939

December 1948 By RICHARD S. JACKSON, GEORGE R. HANNA -

Class Notes

Class Notes1931

December 1948 By A. W. LAUGHTON, WILLIAM H. SCHULDENFREI, CHARLES S. MCALLISTER -

Article

ArticlePAT KANEY: A Tribute

December 1948 By LAUREN N. SADLER '28,

Lettter from the Editor

-

Lettter from the Editor

Lettter from the EditorEditorial Comment

NOVEMBER 1927 -

Lettter from the Editor

Lettter from the EditorFor opinions which appear in these columns the Editors alone are responsible

May 1929 -

Lettter from the Editor

Lettter from the EditorEditorial Comment

OCTOBER 1931 -

Lettter from the Editor

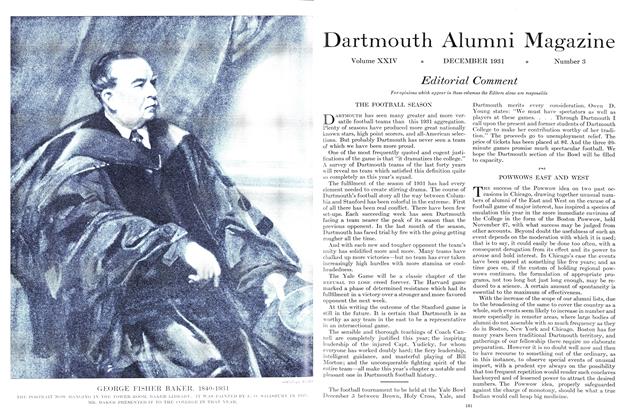

Lettter from the EditorEditorial Comment

DECEMBER 1931 -

Lettter from the Editor

Lettter from the EditorIn Keeping With This Month's Cover Story, The Review Barks Up Dartmouth's Tree.

MAY 1992 -

Lettter from the Editor

Lettter from the EditorWhy We Run "Cause" Advertising

MAY • 1988 By THE EDITORS