One of those things I remember from my freshman year was the talk Robert Frost gave to our class. He liked talking to freshmen, he said, and we were appropriately flattered. As it turned out, it was the last public lec-ture of his long, productive life. This man, the uncrowned poet laureate of America, was something of a tradition in Hanover. Although he had only stayed a few short weeks as a Dart-mouth freshman himself (and never took an A.B. anywhere), he returned periodically to his alma mater to teach or to deliver lectures such as the one we were about to hear. So we actually had professors who had known Frost well and this was very impressive for most of us Pea Greeners and also for our parents, who wanted to be sure that the three grand they were shelling out for an Ivy education was the bargain it was supposed to be. All the world had seen Frost on TV in 1961 at John F. Kennedy's inauguration in the unrelenting glare of the January sun. There had been a fire on the podium, I recall, and Frost astounded everyone he was very old and the situation precarious as he eventually cast his papers aside and recited the poem "The Gift Outright" from memory. It was the kind of drama Frost must have loved, especially since, as best supporting actor, he performed so brilliantly.

In anticipation of Frost's arrival, the Bookstore stocked extra copies of his latest book, a slender volume of poems called In the Clearing, which many of us bought in hopes of having him autograph. I bought it, of course, and got bored waiting and waiting for the admiring throng to clear and headed back to Topliff after his talk. Holden Caulfield was my hero then, and he probably would have been dis gusted that I had made the (for me) uncharacteristically intellectual gesture of buying a book not required for any of my courses. Particularly since I had bought it not so. much to read, but primarily to have signed by a famous most famous living alumnus.

The College was proud of its newest facility the Hopkins Center still redolent with the smell of newly poured concrete and fresh paint. And Frost was in fine form that night the man and the masque, his lovely white hair behaving badly from time to time on stage in Spaulding Auditorium. He ended his presentation not with one of his familiar lyrics, but with a rhymed couplet:

Forgive, O Lord, my little jokes on TheeAnd I'll forgive Thy great big one on me.

I was bemused and, to be honest, genuinely disappointed. That same sentimentality that makes Dartmouth men and women want to come home to Hanover was running full tilt and desperately wanted "Stopping by Woods" or "Birches" something New England, something idyllic, for the finale. I never did shake his hand that November night in 1962, but by the time I finished my doctorate in English many years later at Chapel Hill, I had come to know Frost pretty well. The gentrified view of the great, good New England poet easy to like, easy to read, eminently quotable - (a view, incidentally, nurtured early in my education) gave way to a perception that he was a much tougher poet, a much better poet than I ever suspected, once you learned how to hear the music between the lines.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

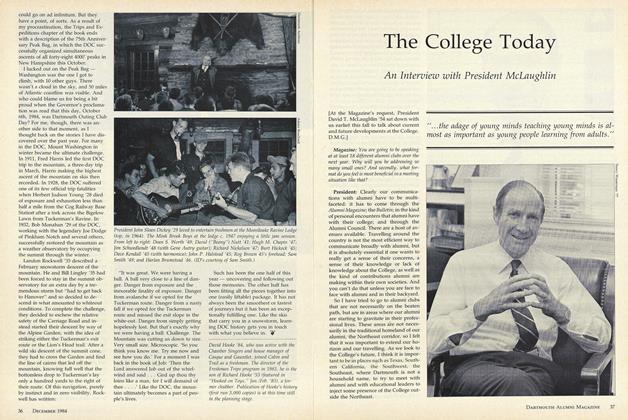

FeatureThe College Today

December 1984 -

Cover Story

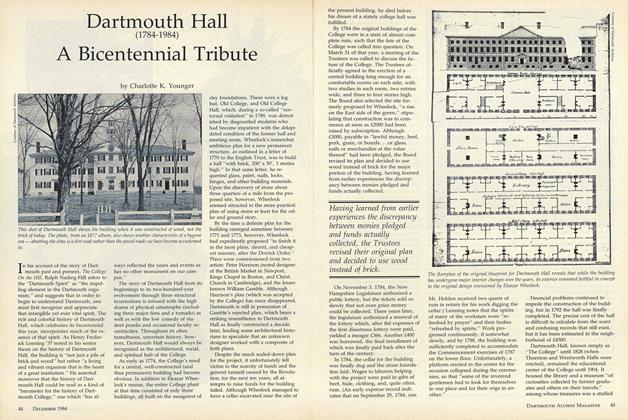

Cover StoryDartmouth Hall (1784-1984) A Bicentennial Tribute

December 1984 By Charlotte K. Younger -

Feature

FeatureChronicling the DOC

December 1984 By David O. Hooke '84 -

Feature

FeatureHanover's Bests

December 1984 -

Article

ArticleLover of parades

December 1984 By Peggy Sadler -

Class Notes

Class Notes1940

December 1984 By Richard J. Goulder

Douglas Greenwood

-

Lettter from the Editor

Lettter from the EditorVisions and Revisions

SEPTEMBER 1983 By Douglas Greenwood -

Lettter from the Editor

Lettter from the EditorExcelsior!

APRIL 1984 By Douglas Greenwood -

Lettter from the Editor

Lettter from the EditorContinuing Education

APRIL • 1985 By Douglas Greenwood -

Lettter from the Editor

Lettter from the EditorSome Thoughts on Commencement, 1985

June • 1985 By Douglas Greenwood -

Lettter from the Editor

Lettter from the EditorThe Place of Art

SEPTEMBER 1985 By Douglas Greenwood -

Lettter from the Editor

Lettter from the EditorYou Can't Go Home, etc.

OCTOBER 1985 By Douglas Greenwood

Lettter from the Editor

-

Lettter from the Editor

Lettter from the EditorEditorial Comment

DECEMBER 1927 -

Lettter from the Editor

Lettter from the EditorA Freshman Writes Home

December 1940 -

Lettter from the Editor

Lettter from the EditorRound the Girdled Earth

October 1944 -

Lettter from the Editor

Lettter from the EditorPassages

JANUARY/FEBRUARY 1984 By Douglas Greenwood -

Lettter from the Editor

Lettter from the EditorSome Thoughts on Commencement, 1985

June • 1985 By Douglas Greenwood -

Lettter from the Editor

Lettter from the EditorTo an old friend

NOVEMBER • 1985 By Douglas Greenwood