John Phillips Professor of Religion

Hans Penner teaches religion by posing as the devil's advocate. The paradox, in this case, is not a contradiction in terms, as anyone knows who has heard him talk about teaching at Dartmouth.

A scholar of myths and rituals and the methodological problems in the understanding of religions, Penner uses his own secularized translation of the Biblical story of Adam and Eve to illuminate what he calls the "adventure," and the risk, of teaching - of encouraging the pursuit of knowledge.

His translation of that "myth" underlines how little of the reality of scholarship is reflected in the stereotype of the scholar's life of contemplative serenity. Rather, as he explains it, academic life pulses with intellectual challenge, conflict, and tension.

In his analogy to the banishment of Adam and Eve from the Garden of Eden, Penner casts the contemporary teacher in the role of the serpent which first tempted Eve to partake of the forbidden fruit from the tree of knowledge. "I see it as our task as college teachers to shine that apple, still symbolizing knowledge, as bright as we possibly can and to hold it out to our students to bite."

In a very real sense, he says, the results are disconcerting to the student who does indeed bite, who gives rein to intellectual appetites. Once tasting the fruit, the student is transported out of youth's garden of innocence into the realm of critical thought where there is no certitude.

Penner, whose towering height adds a physical dimension to his towering authority on the religions of Asia, gives short shrift to any nostalgia over the loss of an innocence based on uncritical acceptance of the world as it may appear. That loss, he contends, is inevitable in the process of learning. Indeed, he maintains that there can be no progress in human understanding of the world and man's place in it without developing the critical faculties of the best minds of each generation.

To Penner, human knowledge is rarely advanced by confirming theory, concept, or myth. To the contrary, man grows in knowledge by what he calls disconfirming or falsifying - finding flaws in accepted or conventional wisdom through the application of critical reasing to observation and experience.

It is this process, he claims, that opens the way for the construction of new theories and concepts consonant with known data - in harmony until these constructs are also found faulty, triggering anew the search for additional facts and the insights and theories deriving from them. "It is a process as painful to the teacher or scholar as it is initially disorienting to the student," he notes, "because you know that built into your conclusions at any time are hidden flaws in logic or evidence that others sooner or later are going to find." The consequent challenges comprise part of the tension, the adventure, and the fun of academe, he says.

Referring to Dartmouth undergraduates in this context, Penner is quick to praise: "Most students do bite the apple and, when they do, they give you a run for your money because most of them are really sharp, bright young people."

Meanwhile, he has not spared himself, often becoming his, own severest critic. In his study of the myths (symbolic language) and rituals (symbolic behavior) of religions as representing the distillations by various cultures and sects of their most profound visions of man's place and purpose, he has pursued and rejected a series of conceptual approaches.

Early on, Penner followed the Freudian line that religious myths and rituals were little more than illusions, emotional representations of desired reality - in effect, symptoms of social neuroses - until he found that thesis wanting in both logic and substance. Then he moved on to an approach which sees religions as functioning simply to meet the needs of human societies. Finding in that interpretation too much that seemed false or trivial, he is now exploring the structure of religious myths and rituals. Here Penner seeks in the roots of the structures the clues to their meanings, a fruitful quest so far that has taken him into the arcane world of contemporary linguistics, where he sees analogs to his own research, and, partly a result, into the fields of statistics and computing.

In the middle distance, Penner will also be taking a large body of his scholarly work beyond the classroom and the study and subjecting it to the scrutiny and the challenge of his academic peers. That will occur within 12 to 18 months with publication of a book, recently completed in manuscript, which for working purposes he has entitled Mythological Approachesto the Study of Religion.

A native of Sacramento, Penner started east in 1954 when he entered the University of Chicago. There he earned a bachelor of divinity degree, an M.A., and a Ph.D., doing his doctoral studies in the history of religion with special attention on the religious traditions of Asia. The move across the continent was completed in 1965, the year he completed his doctorate when he joined the Dartmouth faculty. In 1972, he was appointed to the John Phillips Professorship, the oldest academic chair at the College, established in 1774 through an endowment from John Phillips, then a Dartmouth Trustee and also the founder of Phillips Exeter Academy.

Penner's studies have taken him around the world, from Heidelberg, Germany, to Hyderabad, India; he is a frequent contributor to professional journals and books, including the 1966 and 1971 editions of History of Religions and the 15th edition of the Encyclopaedia Britannica. He has been active in faculty affairs, having served for three years as chairman of the Committee for Educational Planning, which proposed the first plan for year-round operation of the College. He is a former chairman of the Religion Department and now heads a new program in Asian Studies. He also has served on the faculty of the Dartmouth Institute.

While he insists on uncompromising objectivity in his scholarship, he is a little more indulgent when it comes to Dartmouth and the study of religion here. "I am convinced," he says, "that we have the best department of religion of any college in the country. How's that for bias?"

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

FeatureBeating the Odds

May 1975 By IRVING H. LEVITAS, M.D. -

Feature

FeatureBlack in the White Academy

May 1975 By WARNER R.TRAYNHAM -

Feature

FeatureRalph Sterner: See-er

May 1975 By RALPH STEINER -

Feature

FeatureA MEMORANDUM

May 1975 By JAMES L. FARLEY '42 -

Article

ArticleWhere the Grass Looks Green

May 1975 By JACK DEGANGE -

Class Notes

Class Notes1948

May 1975 By FRANCIS R. DRURY JR., HARTHON I. MUNSON

R.B.G.

-

Article

ArticleHEINZ VALTIN

February 1974 By Andrew C. Vail Memorial, R.B.G. -

Article

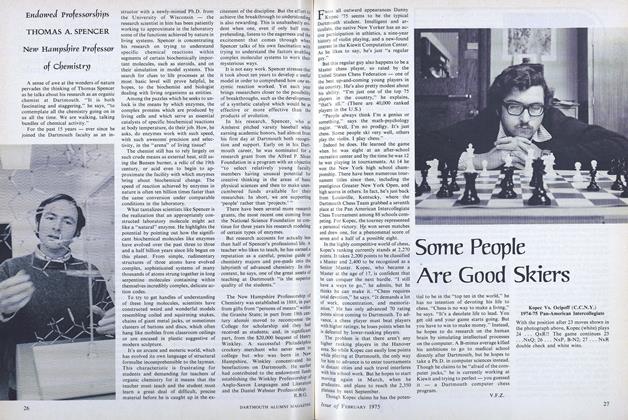

ArticleEndowed Professorships

FEBRUARY 1973 By FRED BERTHOLD JR. '45, R.B.G. -

Article

ArticleIt's Still "Men of Dartmouth"

NOVEMBER 1972 By R.B.G. -

Article

ArticleGORDON J.F. MACDONALD

October 1973 By R.B.G. -

Article

ArticleHAROLD L. BOND '42

October 1974 By R.B.G. -

Article

ArticleTHOMAS A. SPENCER

February 1975 By R.B.G.

Article

-

Article

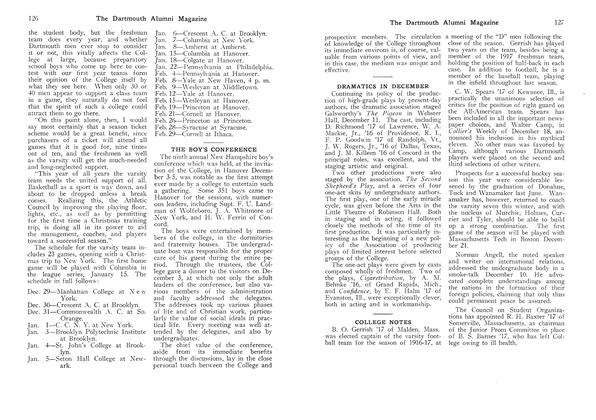

ArticleTHE BOY'S CONFERENCE

January 1916 -

Article

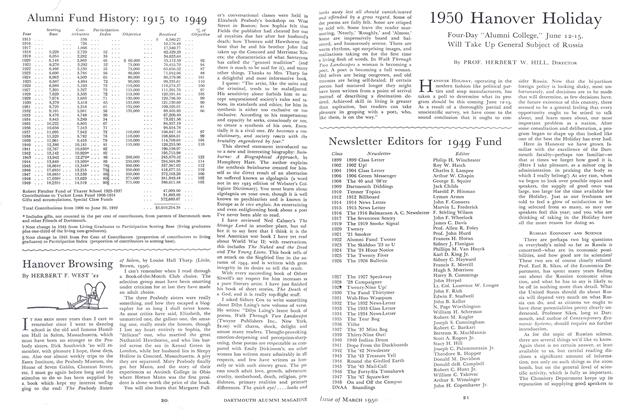

ArticleAlumni Fund History: 1915 to 1949

March 1950 -

Article

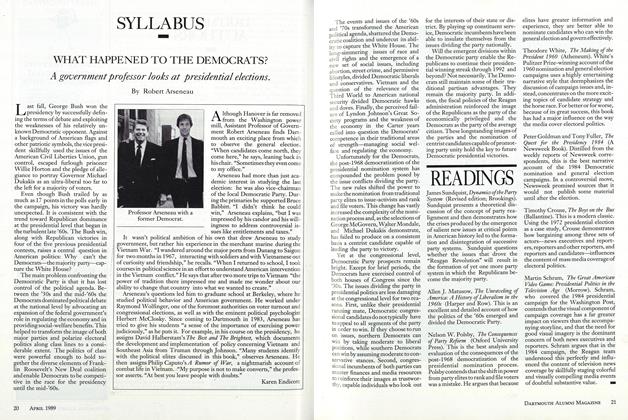

ArticleREADINGS

APRIL 1989 -

Article

ArticleThe Undergraduate Chair

NOVEMBER 1966 By ART HAUPT '67 -

Article

Article"Quite a Group"

Sept/Oct 2005 By JAMES WRIGHT -

Article

ArticleVox in the Box

SEPTEMBER 1998 By John F. Anderson '34