by Hadley Cantril '28. Office ofPublic Opinion Research, 194J, pp. 75,$1.00.

In this little volume Dr. Cantril has attempted to state some problems and to suggest hypotheses about our understanding of man's social behavior. Far from being a finished product, he considers it to be merely a starting point for discussion or a stimulus for new and more penetrating insights into man's activities.

That we need a clearer understanding of man's social behavior will nowhere be denied. What makes the Russians tick and, for that matter, the Americans? Why do management officials and union leaders refuse to see the desirability of cooperative action? Why are race prejudice and religious hostility, in Palestine, the Deep South, and other areas, persistent sources of conflict and violence?

The point which Cantril considers to deserve first mention is the fact that man's development and behavior depend upon his specific purposes. This means that we will "see," and act upon, features of our environments which at our needs; other aspects will be ignored. Thus, a man who is hungry will perceive and react to food objects, while paying no attention to otherwise interesting items in his environment.

Even in perceiving our physical surroundings, these personal factors enter. As Adelbert Ames has shown, in the extraordinary perceptual demonstrations he has developed at Dartmouth (and Cantril gives Ames full credit for stimulating his thinking on these lines), all our perceptions seem to be related to some concept of purpose or possible action. We see as "good" those situations which further our proposed acts, and as "bad" those which interfere with our plans for action.

"Social" perceptions are defined by Cantril as those which are capable of two-way interaction—we can do something to the stimulus and it can do something to us. To take a very obvious example, a union officer sees an industrial relations executive as someone who may affect his plans, and conversely, the industrial relations man may be affected by his (union) actions. The way in which this perception is organized, e.g., the "goodness" or "badness" of the executive as seen by the unionist, has a great deal to do with the prospects for labor peace.

Since all perceptions seem to be actionrelated, Cantril suggests that much of the public disinterest and apathy, e.g., on Russia, the atom bomb and the UN, may be a result of the fact that the individual feels helpless "to act. If clear paths of action are open, a different attitude is usually manifest. Our social purposes inevitably must be related to those of other human beings. If these can be focused around common acts and purposes, we shall have social cooperation and peace. If we ignore or oppose the purposes and action-tendencies of other peoples, the results necessarily must be conflict, violence and war.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Books

BooksDeaths

June 1948 -

Class Notes

Class Notes1918

June 1948 By ERNEST H. EARLEY, DONALD L. BARR, DAVID L. GARRATT -

Class Notes

Class Notes1912

June 1948 By HENRY K. URION, RALPH D. PETTINGELL, ROSCOE G. GELLER -

Article

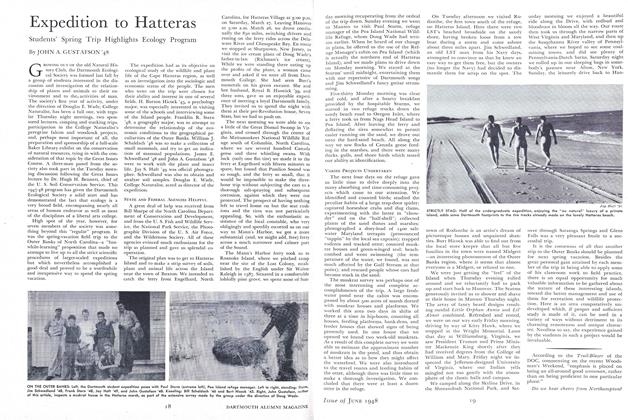

ArticleExpedition to Hatteras

June 1948 By JOHN A. GUSTAFSON '48 -

Article

ArticleA SENIOR'S VERDICT

June 1948 By PHILIP E. BOOTH '47 -

Class Notes

Class Notes1943

June 1948 By FRED F. STOCKWELL, WILLIAM T. MAECK, JOHN A. KOSLOWSKI