LETTERS OF GUST AVE FLAUBERT, 1830-1857 Edited by Francis J. Steegmuller '27 Belknap, 1980. 250 pp. $12.50

The monumental Correspondance of Flaubert 13 volumes in the Conard edition represents half a century of intense conversation with his friends, his family, and his mistress of six years, Louise Colet. Its style, sometimes lyrical, or baroque, or Rabelaisian, offers a vivid contrast to the carefully crafted and impersonal language of the novels. It also provides, within the dynamics of interpersonal relations, a wealth of philosophical and aesthetic reflections, work plans, and reading notes precious for the critics. Francis Steegmuller, the well-known Flaubert translator and scholar, published a selection of the letters in 1953. Thanks to his renewed efforts, a larger sampling of Flaubert's correspondence is now accessible to the English reading public. Covering the period 1830-1857, this is the first of a two-volume project based on the recent work being done in France for the new Pleiade edition. Steegmuller intelligently distributes between the letters the essential biographical information in the form of connecting passages which, along with the notes, provide the necessary scholarly background while sustaining dramatic interest. Chapter headings structure the chronology according to the main episodes of Flaubert's life up to the publication of the first novel, Madame Bovary. After years of excruciating debate as to whether "to make the presses groan" or to continue working for himself alone, Flaubert finally "begets the child" ironically during his renewed romance with Louise Colet. The final group of letters evokes the bitter triumph brought about by the trial of the book for "immorality."

The choice of material, as well as in the introductory remarks, illustrates Steegmuller's intention to emphasize the movement toward Bovary and its underlying "poetics." Fortunately, he has not limited his selection to the obligatory compendium of Flaubert's aesthetic opinions, and he has included enough material to give the reader a sense of the existential drama of Flaubert the "artist" and the lover. Through his letters to Louise Colet, we understand that his rejection of marriage, of love as she conceives it, and ultimately of the "woman," is for him one of the "holocausts" that "Art" demands of the writer, for there is an irreconcilable opposition between art and life: "We should immerse ourselves in real life only up to the navel."

One of the effects of Steegmuller's selection, however, is to attenuate Flaubert's tormented negativism. For instance, the sampling of adolescent letters, characterized a little too quickly here as "youthful and naive," is too slim to reveal the depth and variations of his pessimism in the years preceding his famous prophecy: "If I ever do take part in the world, it will be as a thinker and a de-moralizer." Some later deletions within individual letters destroy the jerky movement from the lyrical to the grotesque that illustrates so well Flaubert's search for the "bitter undertaste" of any experience, as in a fragment from Patras which stops on an exalted description of a Greek statue, depriving the reader of the contrasting incongruous passage on the "tit" that follows in the original. Selection is indeed an interpretive process, and the reader is perhaps made insufficiently aware of this fact.

Some of Flaubert's linguistic extravaganzas are simply impossible to translate into English, but Steegmuller has accomplished a sufficient number of brilliant tours de force to convey generally the vehemence of the tone and the richness of the language. Why then, when he has not in other passages balked at erotic language, does he avoid specific terms of female sexuality that Flaubert occasionally used to describe his acute sensitivity? Indeed, the question of Flaubert's androgynous personality has been the subject of serious study.

Even if the present collection is not sufficient to make a companion volume for Sartre's existential psychoanalysis of Flaubert, The Idiot (forthcoming), it offers an extremely rich introduction to his poetics. It helps to place in the proper historical perspective the legend of Flaubert, "father of realism"; it shows that writing is the very first of his "wretched passions." Art has no other model than art itself, and since "prose was born yesterday," Flaubert imposes upon himself the mission of inventing the style of the novel, a style which alone should hold the book together independently of its subject. His dream of a "book about nothing" points to Mallarme more than to Zola.

It is highly fascinating to read this gospel of pure style according to St. Gustave, couched in rough-cut metaphors, in repetitions, in passionate invocations that push the thought forward and expand its reach. "Yes, it is a strange thing, the relation between one's writing and one's personality."

Professor Gaudin, who chairs the RomanceLanguages Department, specializes in theFrench New Novel, surrealism, and the 19th-century novel.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

FeatureThe Dartmouth Animal and The Hypermasculine Myth

September 1980 By Leonard L. Glass -

Feature

FeatureMonitoring Nature's Big Blow-Up

September 1980 By Dan Nelson -

Cover Story

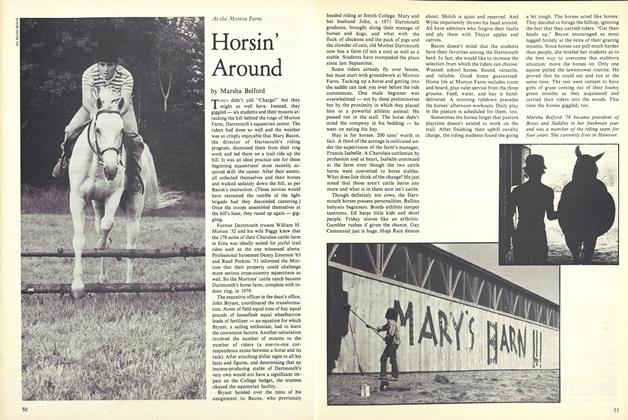

Cover StoryHorsin' Around

September 1980 By Marsha Belford -

Article

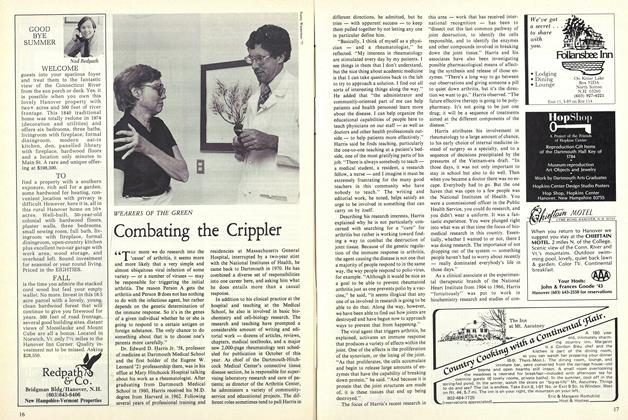

ArticleCombating the Crippler

September 1980 By D.M.N. -

Article

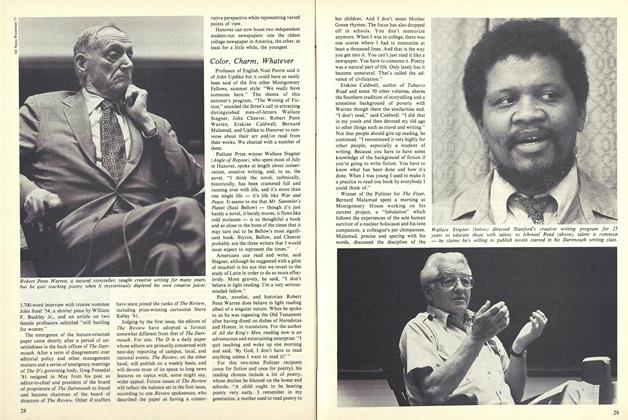

ArticleColor, Charm, Whatever

September 1980 -

Article

ArticleSteel Elected

September 1980

Books

-

Books

BooksVALUE AND DISTRIBUTION

January 1940 By EVERETT W. GOODHUE '00 -

Books

BooksDistant Drum

December 1980 By Everett Wood '38 -

Books

BooksTHE AMERICAN DEMOCRATIC TRADITION: A HISTORY

MAY 1964 By HARRY N. SCHEIBER -

Books

Books"Composition and Literature"

July 1918 By Kenneth Allan Robinson. -

Books

BooksPRACTICAL FLIGHT TRAINING

November 1936 By Ramon Guthrie -

Books

BooksTHE IROQUOIS EAGLE DANCE AN OFFSHOOT OF THE CALUMET DANCE.

February 1954 By ROBERT A. McKENNAN '25