An Expert View of the Northern Polar Regions, New Frontier of Study and International Interest

DARTMOUTH'S CURRENT ACTIVITY in the far north, ranging from the undergraduate trips of the past summer to the recent North Pole flight of Dick Loutree '27, is One feature of a resurgence of interest in the polar regions. Formerly associated with polar bears and penguins, these areas have now, in the minds of some, come to be thought of as the haunts of Russian bears and uranium, along with radar networks and Exercises this and that"Frigid," "Nanook," "Ptarmigan," "Muskox," "Lemming," "Iceberg" or whatnot. There have been well over three hundred weather flights from Alaska to the North Pole and back in recent years, and large ice-breakers made two navigation records as recently as last summer—the one northward of Ellesmere Island, establishing an all-time high for latitude reached under power, and the other by navigating for the first time through Fury and Hecla Strait between the mainland of Canada and Brodeur Peninsula.

New books reaching the Dartmouth Geography department from the U.S.S.R. show that Russia's activities in the far north have not declined, and that the large number of Arctic scientific stations established before the last war are operating and expanding.

ROUND WORLD AND POLAR REGIONS

Because the world is a globe the shortest route between any two places on it is a "Great Circle," which is, so to speak, a straight line on a sphere. Such a line may of course cross any part of the earth, polar or tropical. To illustrate this we can follow straight line courses between three pairs of places such as:

(1) Hanover to Cape Town, South Africa, across the Equator.

(2) Delhi, India, to Hanover across Greenland.

(3) Sydney, Australia to Buenos Aires, across the Antarctic.

Because of the concentration of people in the northern hemisphere—and fairly far north in it—the straight lines between large cities usually run through fairly high latitudes. This is true of direct routes between the United States and Europe or Asia. The east-west routes we have in our minds actually run considerably to the northward on the earth. We can test this by following on a small globe the direct courses between, for example, New York and Hamburg, or San Francisco and Tokio.

There are very practical difficulties about using the shortest routes for sea transport. The obvious problem is the absence of sea from places where it is needed. There are land barriers across the most important of the world's Great Circle routes. The seaway from Boston to Cape Town is fortunately free of such obstruction, but this is an exceptional case. Boston to Madras, India, for example, crosses land for more than half of the route. In the days when the world was being opened up by sea transport port, there were some especially serious barriers of this sort. One was the continuous land mass of North and South America; another was the continent of Africa, really a southerly extension of that of Eurasia. It took many centuries for sailors to find a route from western Europe by sea to the Far East.

There were many attempts to find ways of making an "end run around the continental barriers toward the north. If successful, such routes would, of course, have been far shorter than those to the south. These efforts to navigate the Northeast and Northwest Passages are still going on.

There are very important differences between the areas around the North and South Poles. That around the North Pole is sea-the Arctic Sea-and it is almost surrounded by land. The South Pole, however, is on land, a very high plateau with an area of about 6,000,000 square miles. This land mass is surrounded by water, making it an island, or rather a series of islands. The sea surrounding them provides an uninterrupted water route around the world.

Most of the w-orld's land, apart from the Antarctic, lies in the northern hemisphere. The continents appear to radiate from the north polar sea and to taper off toward the south. This means that there is relatively little land in the southern hemisphere. Because people make their homes on the land, the northern hemisphere is by far the more important economically. Before discussing the far north, let us make a brief excursion to the far south.

THE ANTARCTIC TODAY

Exploration of the Antarctic goes back well over 150 years—and as long ago as 1821 the Czar of all the Russias sent Bellingshausen on a scientific journey there—one which I suspect we shall be hearing a great deal about in the next few years. There is now renewed interest in the Antarctic. Nations are rumored to be rivalling one another in their efforts to stake claims to parts of the six-million-square-mile continent. What are the facts about this international scramble?

There have been three recent United States expeditions to Antarctica and former students of Dartmouth College were members of two of them. The first, called "Operation Highjump," was a United States Navy expedition which sailed early in December, 1946, carrying about 4,000 men in thirteen vessels. Among the most valuable results of the expedition was an immense collection of aerial photographs to be used in mapping the coastline of the Antarctic continent. As the ships were only in the area for a couple of months during the summer, no long-range scientific results were to be expected.

The second United States expedition to the far south, under command of Finn Ronne, sailed during January, 1947, and remained at its base in Grahamland for almost a year. A valuable series of air photographs were obtained, weather observations recorded, and geology studied.

The most recent United States Navy expedition to the Antarctic was that of 1948, in which Commander David Nutt '41, USNR, now Arctic Specialist at Dartmouth, took part. Designed to complete the work of "Highjump" of the previous year, the expedition secured the necessary "ground control" to enable the photographs already taken to be used for mapping. A full report of the undertaking, written by Commander Nutt, appears in Arctic„ the journal of the Arctic Institute of North America, Vol. 1, No. 2.

The British government has been engaged in long-range scientific and administrative work in the Antarctic for many years. There are now about five permanent scientific stations of the Falkland Islands Dependencies Survey in the region, manned by staffs which are changed annually. Apart from the seasonal visits of whalers there are no other expeditions in the Antarctic at present, unless one includes those of the South African and Australian governments on islands in the Southern Ocean. Plans are nearing completion for a large scale expedition under Norwegian command to be supported jointly by Norway, Sweden, and the United Kingdom.' It will reach Queen Maud Land, under Norwegian sovereignty, late in 1949.

Most of the popular interest in the far south in recent years appears to have been due to the resumption of whaling in the area. The object of the whalers is to obtain as much oil and meat as cheaply 35 possible and without the expenditure of scarce currencies. Norway and the United Kingdom have traditionally been the leaders in southern whaling and have particular need of its products.

The present situation in the Antarctic may be summed up by saying that there has been a return to pre-war whaling and scientific work, with the addition for the first time of large-scale scientific-cum-military expeditions from the United States. It is probable that the work to be done in the future will be in the hands of the relatively small groups of scientists at isolated bases typified by the Ronne and British expeditions.

Unfortunately there are political undertones to the present increased activity. Rival claims are being made. The United States government has never formally made any claim to territory in the Antarctic, and it has consistently refused to acknowledge the claims of any other nations in the area. The present international suspicion based on uncertainty about sovereignty is not conducive to good scientific work. Traditionally there has been the freest international interchange of results from expeditions, as also of plans for forthcoming ones. Nowadays there is sometimes a good deal of secrecy. This reduces the value of scientific accomplishments. Fortunately it is still not too late to remedy the situation. The whole of the Antarctic continent not at present under established sovereignty and administration could be turned over to the Trusteeship Council of the United Nations, with scientific exploration under the general supervision of UNESCO. Nations making the greatest sacrifices under such a plan would be those with existing claims—Australia, New Zealand, France, Norway, and the United Kingdom. These countries have it in their power to act in such a way that at any rate one corner of the earth will be spared from the blighting effect of national rivalry.

THE NORTHERN POLAR REGIONS

WHERE precisely is "the Arctic"? Popularly it is considered to be the area within the Arctic Circle, which is shown as a dotted line on most globes and many maps. The line has very little geographical significance. Crossing the Circle makes no difference to the appearance of the land, the sky, or the sea. Certainly, all regions within it do not have the same climate, and it is climate more than anything else that must be considered in estimating potential uses of the far north.

It is now generally agreed that "the Arctic" is that area lying north of the limit of trees—north of the treeline. The limit of trees in North America is approximately where the average July temperature just manages to reach 50° F. South of this line there is an extensive region often called "Subarctic" where coniferous trees grow.

To visit the true Arctic, the resident of the eastern United States need go no farther than Labrador. There, in latitude 55° N., one is beyond the tree-line. On the other hand in the Mackenzie valley of northwestern Canada it is possible to travel as far as 68° N. and still be in wooded country. Obviously latitude is not the only factor that controls the growth of vegetation, and equally obviously the Arctic is much farther south in some areas than others. The coldest settlement in the world is at Oimekon in Siberia, where the difference between the average temperature for the hottest month and the coldest month is about 120° F._from 60° F. to 60° F. below zero. The countryside there is covered with a dense coniferous forest, for this is not the true Arctic and the North Pole is about 2,000 miles away. The coldest temperature recorded in North America is nowhere near the Arctic Sea, but in Yukon where it was 83° F. below zero in January, 1947, and probably touches 80 above zero in an average summer.

EXPLORATION

The first European travellers to the Arctic were on the way to more attractive destinations—usually the Far East. Many of them left their names on our maps, including Frobisher, Baffin, Davis, and Hudson. Over the centuries, the outlines of most of the coasts have been filled in, and additional detail was provided by land expeditions. There is still much of arctic North America that awaits accurate mapping, although the work has been greatly speeded by the use of large aircraft using several cameras simultaneously. In this way the photographic "Lancasters" of the R.C.A.F., for example, covered more than 900,000 square miles in a few months during the past summer. Occasionally there are surprises, such as that in July, 1948, when a photographic aircraft discovered an island covering about 5,000 square miles in Foxe Basin, near Baffin Island, in a region thought to have been reasonably well mapped by explorers. Considerable changes have also been made in the shape of far northern Arctic islands, but there is unlikely to be any very large addition to the present maps and all the territory is in possession of one nation or another.

WHO OWNS THE ARCTIC?

If we consider the Arctic Sea as being a circle about the North Pole, 160° of the 360° it contains are owned by the Soviet Union—whose lands stretch from the Norwegian border in 30 E. long, to an island only a few miles from United States territory in about 170° W. long. In terms of clock time, the U.S.S.R. share of the Arctic

coastline covers about ten or eleven hours. The next largest owner of Arctic real estate is Canada with title over 81° of longitude—a matter of between five and six hours of time zone. These two countries between them thus control about twothirds of the Arctic coastline. Smaller shares are held by Denmark, through possession of Greenland; the United States as owner of Alaska; and Norway, both because of the mainland and through the islands of Spitsbergen and Jan Mayen. Other nations with polar or sub-polar territories, although not with polar coastlines, are Sweden and Finland. Iceland deserves mention although its climate is scarcely Arctic. Looked at on a globe therefore, North America and the U.S.S.R. are "neighbors across the North Pole"— a frontier which today is more important than it was twenty years ago. Realization of this situation brings alarm and despondency to some people.

It is not yet easy to write with certainty about conditions in the northern part of U.S.S.R. The number of visitors from western Europe and North America has been small. While much information has been published in Russian, comparatively little of it is available in English. However, we know the physical geography of the area fairly well, and this determines to a large extent possible developments there. The long Arctic coastline is of limited use for shipping, mainly because of the short open season in summer. While the port of Murmansk is open all the year round, and Archangel can be kept open for all but a few weeks, as one moves farther eastward from the Atlantic conditions become more severe. The central part of the coast can be passed with difficulty for only a couple of months in the summer. Added to an unfortunate coastline is the fact that many of the great rivers of the country flow toward the north—the Ob, Yenesei, Katanga, Lena, and Kolyma are important examples. These rivers are of great significance in a land where roads and railways are scarce—and yet their estuaries open on the Arctic sea. The natural route for the forest and other wealth of interior U.S.S.R. is northward down these river valleys, because the Trans-Siberian Railway cannot transport bulky cargoes economically.

For this reason, if for no other, the authorities of the U.S.S.R. long ago determined to do everything possible to link the river mouths by a regular summer shipping route. It was to begin in the open waters of the North Atlantic and follow the north coast of Eurasia to the Pacific. There were of course other reasons for establishing such a route, such as the need of the Soviet Navy for a short water route between east and west, the importance of consolidating Soviet claims to Arctic sovereignty and the need to develop all available natural resources.

Authorities are agreed that the U.S.S.R. has during twenty years before the last war met with considerable success in its Arctic territories. By 1939—and we have little data about what has happened since—the U.S.S.R. had established a summer shipping route from western Europe to eastern Asia using regular ice patrols, systematic weather reporting, studies of magnetism, hydrography etc., and by maintaining well over fifty permanent northern stations. Ordinary cargo ships from abroad reached Yenesei river ports as far inland as Igarka, where lumber was loaded for export. In the middle thirties the U.S.S.R. built a number of extremely powerful ice-breakers which were at the time the best in the world. Every effort was apparently made to dramatize life in the far north so as to attract young people to service there. Efforts were made to modernize educational methods employed among the native peoples. By 1938 it was generally agreed that the Soviet Union was a leader in Arctic scientific work, and there was fairly full cooperation with United States and other foreign scientists.

THE WAR YEARS IN THE ARCTIC

Many of the military leaders of North America entered the war with the firm conviction that the world was the shape of the maps on their walls—rectangular. The absence of the north polar regions from these maps was simply not noticed. President Roosevelt was something of a pioneer among strategists when he employed a very large, freely moving globe to follow military campaigns. As the years passed the significance of the world's roundness began to dawn on others. The arrival of Japanese forces at Kiska, at first thought of as an expedition up a blind alley, was in time recognized as an invasion along the straight line from Tokyo to the United States. The need for ferrying badly overloaded and underpowered aircraft across the Atlantic emphasized the importance of the shortest over-water routes—and these ran northward. So toward both the northeast and the northwest there slowly grew important wartime air routes. The need for supplying the U.S.S.R. by a northern route—and the fear that routes in lower latitudes by way of Vladivostok and Persia might be closed—led to ambitious plans even for flying across the top of the world, and for sending vessels from the Pacific along the Russian northern sea route to Europe. Thus in one way and another, by 1943 the strategic significance of the North was established. It may be of interest to examine what this meant in practice.

To the northwest ran the air ferry route across Canada to Alaska and so on to Asia. The line of airfields was followed by a highway used primarily to supply them, and by telegraph, telephone and pipe lines. Airfields built across the water in Siberia enabled Soviet pilots to continue westward toward the European fighting front. A similar ferry route ran eastward in a slightly northerly direction, at first by way of Gander, Newfoundland, and later by Goose Bay, Labrador, and eventually by way of Hudson Bay, Baffin Island, mid- Greenland, to Iceland and the north of Britain. There was the beginning of an alternative northwesterly route down the Mackenzie valley in subarctic Canada, through an area with good flying weather and easy terrain toward the Arctic sea and the U.S.S.R., but it was never completed. Among the most elaborate wartime northern projects were the "Crystal" and "Bluie" air bases. No less than five very large flying fields were built in Canada and three in Greenland. Each of these became a thriving community, the population of one of them exceeding five thousand at one time.

In such ways large numbers of aircraft were regularly used in the far north, and much experience in Arctic operations was gained by thousands of men. Better maps were needed, and this led to large scale photographing operations; weather reports were inadequate so that scores of new meteorological stations were established; access to airbases required the building of new roads, or the charting of unknown waters. The work carried out in Canada and Greenland by the United States was done under temporary wartime arrangements. In the case of Canada, the equipmen at the bases was purchased outright as long ago as 1944, although the United States has continued to occupy some sites on a temporary basis. No final arrangement has yet been made in the case of Greenland, although it is well known that Denmark wishes to resume full control of all its territory there.

From the little that is known about wartime developments in the Soviet Arctic, it appears that activities were spurred on by the war. A new railway reaching navigable waters near the Arctic sea was completed, so as to tap coalfields in the interior to supply northern sea route ships with fuel. Service on the northern rivers is said to have been greatly improved and better harbors were constructed at the river mouths. One of the smallest of them in 1939, Tiksi Bay at the mouth of the Lena river, was reported in 1945 to have had more than 235 children born within its limits in the previous year, an indication of a considerable settlement.. Forty-five ocean-going vessels docked there in that year as well as river boats carrying freight inland to Yakutsk. We can assume that the Northern Sea Route Administration has lost none of its enthusiasm for high lati- tude navigation. With the war ended and a new five-year plan in operation, the north is probably entering another period of rapid expansion.

RECENT YEARS

Postwar developments in northern North America have been considerable. They have included a certain amount of military activity, about which, of course, little is known publicly, and a greatly increased drive from civilian agencies. Among the most interesting of the latter is the establishment of new weather stations in northern Canada, under the joint auspices of the Canadian and United States weather bureaus. The lack of far northern weather reports has been a very serious handicap

to forecasters farther south, but five new stations on the northern fringes of Canada should do much to ease the problem. Four of the stations were established by "airlift" and the fifth by sea. The two most remote stations—one on Prince Patrick Island and the other on Isachsen land are in an area which had previously been visited by very few explorers—the most recent of them being Stefansson who was there more than thirty years ago. Today their weather reports appear as regularly as those of many southern stations.

In supplying and establishing such weather stations, powerful ice-breakerssuch as the Northwind and Eastwind of the U. S. Coast Guard—have incidentally carried out most valuable scientific work and in some cases have penetrated seas not previously navigated. Wherever they have travelled in the far north, the modern explorers, equipped with the best scientific aids and human comforts, have commented on the outstanding work of the old explorers who, usually with nothing better than sailing vessels, and without photography, radio or any of our normal aids to surveying, mapped faithfully the lands that they passed, and studied intensively the sites where they wintered.

WHAT NOW?

Those who are concerned with the speedy and peaceful development of the Arctic lands of Alaska, Canada, Greenland, U.S.S.R. and other countries can only view with regret the assumption made in many contemporary political and military commentaries, that a coming war will be fought across the Arctic regions. It is, we are told, to be a struggle with long-range aircraft and guided missiles, both of which will make use of the short-cuts across the top of the world. Planners are busily engaged drawing Great Circle routes on polar projection maps and teaching that the polar basin will be the cockpit of tomorrow's war. As a geographer who has of necessity to study the whole world, it is my impression that the planners have allowed enthusiasts for the polar projections to put something over on them. There is a distance of about five thousand miles between the main line of the Canadian National Railways and the Trans-Siberian Railway,, with mighty little to aid and comfort anyone in between. If there were to be a war in the next decade, it seems to me that while there might be excursions into the Arctic from various directions, the main lines of attack would not be dissimilar from those employed by Julius Caesar, Alexander the Great, and Ghengis Khan. Arctic campaigns would, of course, be of nuisance value, but it appears at present quite out of the question for large numbers of men to operate on the ground under war conditions in the polar regions.

The hope of the scientist is that the Arctic regions will be left to the peaceful development that has so far characterized them, and that the traditional international collaboration there may be allowed to continue without undue restriction. Whether for war or peace, there can be no question that Arctic research in future will need to be done on an international basis, with each nation contributing its men or means to the discovery, correlation and publication of scientific facts. Among the happiest of moves in this direction was the establishment four years ago of the Arctic Institute of North America. Dartmouth College was well represented among those who founded the Institute and is still very closely associated with it. Anyone interested in scientific or other activities in the polar regions would be well advised to become an Associate of the Institute, if only to secure its periodical, Arctic, which is edited in Hanover. Both government and private agencies have contributed towards the funds of the Arctic Institute, and important exploratory journeys have already been made by scientists assisted from its grants-in-aid fund. The present generation of Dartmouth students are finding increasing opportunities for high latitude adventure and research through contacts with the Institute offices in New York and Montreal.

LAND OF THE MIDNIGHT SUN: This striking photograph, taken at 12:15 a.m., shows the approach to Greenland glaciers in the Baffin Bay area, with a large collection of icebergs in the far background.

PROFESSOR TREVOR LLOYD, right, author of this article, and David C. Nutt '41, Arctic Specialist at Dart- mouth, examining a wood carving from Greenland. Both are Fellows of the Arctic Institute of North America. Professor Lloyd has investigated the Far North since 1935, was Canadian consul at Godthaab, Greenland, in 1944-45, and recently completed a special study of Northern Canada for the Canadian Institute of International Affairs. Mr. Nutt has made trips to both the Arctic and Antarctic and as a U. S. Navy commander during the war was executive officer of the USS BOWDOIN which made hydro- graphic surveys off the coast of Greenland.

ICE PACK: The USCGC NORTHLAND, famous for its work on the Greenland Patrol, noses through an ice pack in Arctic waters. Such a pack may congest far north waters for hundreds of square miles.

GLOBAL MAP OF THE ARCTIC DRAWN FOR THE MAGAZINE BY VAN HARVEY ENGLISH, DARTMOUTH GEOGRAPHER AND MAP LIBRARIAN

NATIVE OF THE CANADIAN NORTH: This Eskimo of the Great Whale district, Quebec, stands before a typical igloo home. A happy nomad, he lives by fishing and hunting for seal, caribou and white whale.

INTERNATIONAL ICE PATROL: A crew member of the USCGC MENDOTA watches a Coast Guard plane fly over a large iceberg. The combined air and surface patrol, also using radar, reports ice menacing navigation in the North Atlantic.

FAMOUS ARCTIC EXPLORER AT DARTMOUTH: During his visit to Hanover last winter Dr. Vilhjalmur Stefansson aroused great interest by showing undergraduates how to build an Eskimo snow house.

PROFESSOR OF GEOGRAPHY

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Article

ArticleConcerning Admissions

April 1949 By H. CLIFFORD BEAN '16 -

Lettter from the Editor

Lettter from the EditorLetter from Oxford

April 1949 By CHARLES G. BOLTE '41 -

Class Notes

Class Notes1918

April 1949 By ERNEST H. EARLEY, DONALD L. BARR, RICHARD A. HOLTON -

Article

ArticleDeaths

April 1949 -

Class Notes

Class Notes1929

April 1949 By F. WILLIAM ANDRES, EDWIN C. CHINLUND, GEORGE B. REDDING -

Class Notes

Class Notes1914

April 1949 By DR. WALLACE H. DRAKE, RUFUS L. SISSON JR., JOHN F. COiNNERS

Article

-

Article

ArticleSpecialized Commissions

August 1942 -

Article

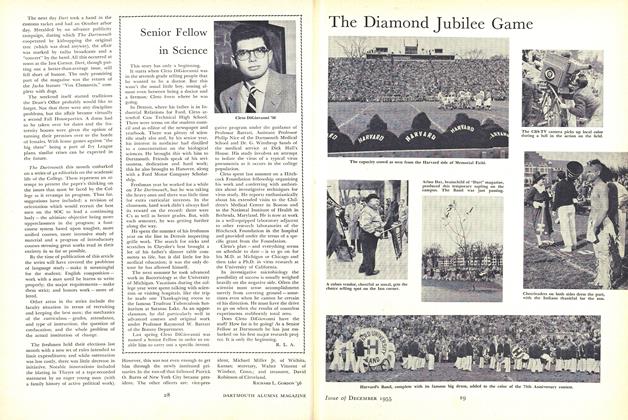

ArticleThe Diamond Jubilee Game

December 1955 -

Article

ArticleGraduate Study Grants Available to Alumni

DECEMBER 1972 -

Article

ArticleGive a Rouse for

APRIL • 1987 -

Article

ArticleA Free Press?

February 1947 By A. J. LIEBLING '24 -

Article

ArticleThayer School News

January 1938 By Edward S. Brown Jr.