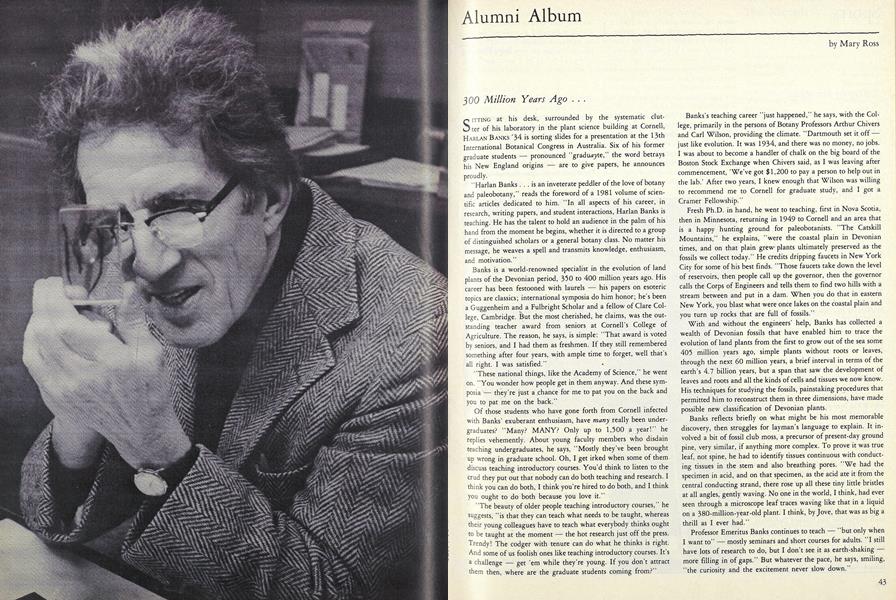

SITTING at his desk, surrounded by the systematic clutter of his laboratory in the plant science building at Cornell, HARLAN BANKS '34 is sorting slides for a presentation at the 13th International Botanical Congress in Australia. Six of his former graduate students - pronounced "graduate," the word betrays his New England origins - are to give papers, he announces proudly.

"Harlan Banks... is an inveterate peddler of the love of botany and paleobotany," reads the foreword of a 1981 volume of scientific articles dedicated to him. "In all aspects of his career, in research, writing papers, and student interactions, Harlan Banks is teaching. He has the talent to hold an audience in the palm of his hand from the moment he begins, whether it is directed to a group of distinguished scholars or a general botany class. No matter his message, he weaves a spell and transmits knowledge, enthusiasm, and motivation."

Banks is a world-renowned specialist in the evolution of land plants of the Devonian period, 350 to 400 million years ago. His career has been festooned with laurels his papers on esoteric topics are classics; international symposia do him honor; he's been a Guggenheim and a Fulbright Scholar and a fellow of Clare College, Cambridge. But the most cherished, he claims, was the outstanding teacher award from seniors at Cornell's College of Agriculture. The reason, he says, is simple: That award is voted by seniors, and I had them as freshmen. If they still remembered something after four years, with ample time to forget, well that's all right. I was satisfied."

"These national things, like the Academy of Science, he went on. "You wonder how people get in them anyway. And these symposia they're just a chance for me to pat you on the back and you to pat me on the back."

Of those students who have gone forth from Cornell infected with Banks' exuberant enthusiasm, have many really been undergraduates? "Many? MANY? Only up to 1,500 a year! he replies vehemently. About young faculty members who disdain teaching undergraduates, he says, "Mostly they've been brought up wrong in graduate school. Oh, I get irked when some of them discuss teaching introductory courses. You'd think to listen to the crud they put out that nobody can do both teaching and research. I think you can do both, I think you're hired to do both, and I think you ought to do both because you love it."

The beauty of older people teaching introductory courses, he suggests, "is that they can teach what needs to be taught, whereas their young colleagues have to teach what everybody thinks ought to be taught at the moment - the hot research just off the press. Trendy! The codger with tenure can do what he thinks is right. And some of us foolish ones like teaching introductory courses. It's a challenge - get 'em while they're young. If you don't attract them then, where are the graduate students coming from?

Banks's teaching career "just happened," he says, with the College, primarily in the persons of Botany Professors Arthur Chivers and Carl Wilson, providing the climate. "Dartmouth set it off just like evolution. It was 1934, and there was no money, no jobs. I was about to become a handler of chalk on the big board of the Boston Stock Exchange when Chivers said, as I was leaving after commencement, 'We've got $1,200 to pay a person to help out in the lab.' After two years, I knew enough that Wilson was willing to recommend me to Cornell for graduate study, and I got a Cramer Fellowship."

Fresh Ph.D. in hand, he went to teaching, first in Nova Scotia, then in Minnesota, returning in 1949 to Cornell and an area that is a happy hunting ground for paleobotanists. "The Catskill Mountains," he explains, "were the coastal plain in Devonian times, and on that plain grew plants ultimately preserved as the fossils we collect today." He credits dripping faucets in New York City for some of his best finds. "Those faucets take down the level of reservoirs, then people call up the governor, then the governor calls the Corps of Engineers and tells them to find two hills with a stream between and put in a dam. When you do that in eastern New York, you blast what were once lakes on the coastal plain and you turn up rocks that are full of fossils."

With and without the engineers' help, Banks has collected a wealth of Devonian fossils that have enabled him to trace the evolution of land plants from the first to grow out of the sea some 405 million years ago, simple plants without roots or leaves, through the next 60 million years, a brief interval in terms of the earth's 4.7 billion years, but a span that saw the development of leaves and roots and all the kinds of cells and tissues we now know. His techniques for studying the fossils, painstaking procedures that permitted him to reconstruct them in three dimensions, have made possible new classification of Devonian plants.

Banks reflects briefly on what might be his most memorable discovery, then struggles for layman's language to explain. It involved a bit of fossil club moss, a precursor of present-day ground pine, very similar, if anything more complex. To prove it was true leaf, not spine, he had to identify tissues continuous with conducting tissues in the stem and also breathing pores. "We had the specimen in acid, and on that specimen, as the acid ate it from the central conducting strand, there rose up all these tiny little bristles at all angles, gently waving. No one in the world, I think, had ever seen through a microscope leaf traces waving like that in a liquid on a 380-million-year-old plant. I think, by Jove, that was as big a thrill as I ever had."

Professor Emeritus Banks continues to teach - "but only when I want to" - mostly seminars and short courses for adults. "I still have lots of research to do, but I don't see it as earth-shaking - more filling in of gaps." But whatever the pace, he says, smiling, "the curiosity and the excitement never slow down."

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

Feature"Now we had to go in different directions"

November 1981 By Rob Eshman -

Feature

FeatureA record of their fame

November 1981 By Eddie O'Brien -

Feature

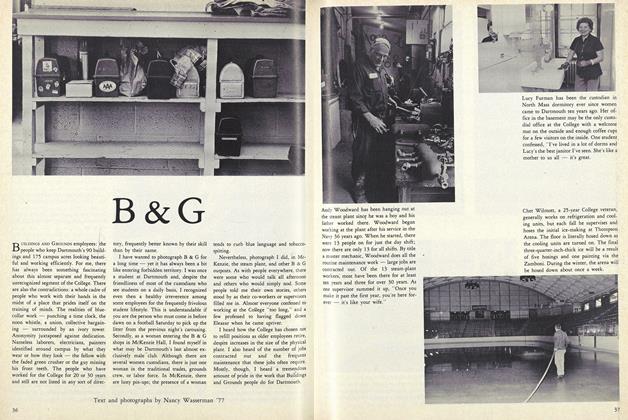

FeatureB & G

November 1981 -

Article

ArticleMaster Carpenter, Journeyman Blackmailer

November 1981 By Shelby Grantham -

Class Notes

Class Notes1959

November 1981 By William G. Long -

Class Notes

Class Notes1961

November 1981 By Robert H. Conn

Mary Ross

-

Feature

FeatureOMBUDSMAN

OCTOBER 1971 By MARY ROSS -

Article

ArticleYankee Editor

MARCH 1972 By MARY ROSS -

Article

ArticleSharing Faith and Fear

MAY 1982 By Mary Ross -

Article

ArticleStrict Reconstructionist

SEPTEMBER 1983 By Mary Ross -

Article

Article"To the conquest of the unknown and the advancement of knowledge."

MARCH 1984 By Mary Ross -

Article

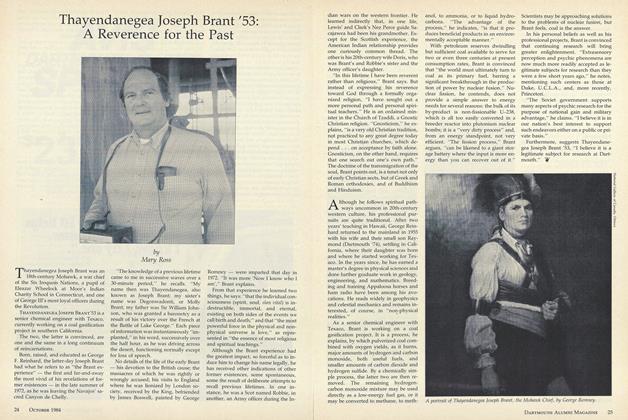

ArticleTha yendanegea Joseph Brant '53: A Reverence for the Past

OCTOBER 1984 By Mary Ross

Article

-

Article

ArticleTHE DRAMATIC CLUB

-

Article

ArticleCollege Presidents

March 1951 -

Article

ArticleSTATEMENT of ownership, management

NOVEMBER 1972 By CHARLES E. WIDMAYER -

Article

ArticleMedical School

By HARRY W. SAVAGE '26 -

Article

Article...KILLED THE CAT

MARCH 1963 By NEVIN D. SCHREINER '64 -

Article

ArticleThayer School

June 1942 By William P. Kimball '29