The Dartmouth went on to state that its purpose was to determine where the Dartmouth man stood in relation to the restrictive clauses on race and creed which served as partial barriers to fraternity membership. The editorial gave three reasons for conducting the poll. First, it felt that there had been enough talk on the issue. Secondly, the time for constructive action was at hand; and thirdly, TheDartmouth believed that "the basis for any constructive action concerning undergraduate activity was to be found in the opinion of the undergraduate body itself."

The note had been sounded, and on the following day four student organizations went out to solicit the opinions in the College. Representatives from the Dartmouth Broadcasting System, the National Students Association, the Human Rights Society, and the Dartmouth Christian Union visited the students in every dormitory and fraternity in search of the answers to three questions. The ballot handed to each man read as follows:

In the constitutions, charters, or by-laws of some fraternities, there are clauses which prohibit the initiation of individuals because of race, or religion.

Fraternities with such clauses exist at Dartmouth and at most other colleges.

1. In my opinion, these restrictive clauses should be ( ) eliminated at Dartmouth. ( ) maintained at Dartmouth. ( ) I am undecided as to this issue. 2. Are you a member or pledge of a fraternity? ( ) Yes ( ) No 3. Are you a ( ) '50 ( ) '51 ( ) '52 ( ) '53 ( ) other class

The ballot was made short and lucid so that undergraduates might express their opinions easily and quickly. In addition, pollsters were instructed not to discuss the issue of the survey, but merely to see that all ballots were folded and placed inside a sealed envelope.

No one was skipped intentionally. Dick's House was visited, off-campus residences were solicited, and even the pollsters got a crack at the ballot box when they had turned in their envelopes.

On the night of the survey, Prof. George F. Theriault of the Sociology Department headed the counting and tallying of ballots. He was assisted by three impartial student leaders. This group comprised Tom O'Connell '50, president of the Undergraduate Council, Bob Kilmarx '50, president of Palaeopitus, and Jeff O'Connell '50, president of Green Key.

The Dartmouth went to press that night with the tally. The poll had covered 2359 students or eighty per cent of the College, and when the final totals were on the boards, it was 9-2 against restrictive clauses. Of the men polled, i,754 or 74.3 per cent voted in favor of elimination while 375 men voted to maintain them and 230 were undecided.

Most of us had expected this kind of result; the poll clinched the issue. Eighty per cent was good enough for us, and no matter how anyone looked at the hand writing on the wall, it spelled the same thing—ELIMINATION.

In a front page editorial which accompanied the results, The Dartmouth took the next logical step and interpreted the results of the poll as a mandate for the removal of restrictive clauses from the campus. Following closely, they asked, "Who is the mandate for? Who should accomplish this removal?"

Well, the wheels had been turning for a long while, slowly at times, but still they'd been turning.

At a meeting on October 26, one week before the all-College poll was taken, the Dartmouth Interfraternity Council voted an endorsement of a recommendation by the Northeastern Regional Interfraternity Conference that national fraternities eliminate constitutional clauses which discriminate on the basis of race, creed or color. The same endorsement, previously voted on by representatives of fraternities at the National Interfraternity Conference at Amherst on October 17, was to be pushed further when the Conference assembled again in Washington, D. C., on November 24.

Right now there are a a social fraternities at Dartmouth, all but two having national affiliation. Twelve of these houses claim they do not have restrictive clauses in their charters. Both the IFC survey and that made by The Dartmouth arrives at the same conclusion—at Dartmouth we're all brothers.

And, President Dickey stands behind us. His comments after viewing the results of the poll were, in essence, the same as those he had stated previously in a booklet on Dartmouth fraternities.

In part, the President's statement reads:

"The possibility of the national affiliation of fraternities becoming an acute matter of college policy seems to me at present unlikely except in one important respect. The college has a responsibility for all educational influences connected with it and it cannot look with complacence upon any undesirable external educational influence on the campus.

"This College neither teaches nor practices religious or racial prejudice and I do not believe that it can for long permit certain national fraternities through their charter provisions or national policies to impose prejudice on Dartmouth men in their free selection of their fraternal associates."

The president continues, saying:

"I want to be very clear that I am opposed to any suggestion that the chapters must or should take any man whom they do not themselves want as a member; but I am also very clear that I do not think it a healthy educational influence to havDartmouth students forbidden from 'taking in' respected Dartmouth friends because of racial or religious prejudices of a remote national fraternity charter or policy.

"I personally simply want the practical assurance that the undergraduates in Dartmouth fraternities are free to take or reject any eligible Dartmouth student on the basis of the undergraduate's own preferences and prejudices rather than someone else's.

"If this practical assurance is not forthcoming from certain national fraternities, it is due you now to make clear that those nationals cannot continue to be regarded as bringing a desirable educational influence on the Dartmouth campus."

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Article

ArticleOUR GREATEST ISSUE

December 1949 By BRUCE W. KNIGHT -

Article

ArticleNew Development Council Formed

December 1949 -

Class Notes

Class Notes1923

December 1949 By TRUMAN T. METZEL, COLIN C. STEWART, JULIUS A. RIPPEL -

Class Notes

Class Notes1918

December 1949 By ERNEST H. EARLEY, DONALD L. BARR, DAVID L. GARRATT -

Class Notes

Class Notes1943

December 1949 By ELMER G. STEVENS JR., STANTON E. PRIDDY -

Article

ArticleIt's An Old Spanish Custom of Speech

December 1949 By CHARLES L. YOUMANS '20

Bill Mulligan '50

-

Article

ArticleTHE HANDWRITING ON THE WALL

December 1949 By Bill Mulligan '50 -

Article

ArticleThe Undergraduate Chair

January 1950 By Bill Mulligan '50 -

Article

ArticleThe Undergraduate Chair

February 1950 By Bill Mulligan '50 -

Article

ArticleThe Undergraduate Chair

March 1950 By Bill Mulligan '50 -

Article

ArticleMilestones

April 1950 By Bill Mulligan '50 -

Article

ArticleThe Undergraduate Chair

June 1950 By Bill Mulligan '50

Article

-

Article

ArticleOUTING CLUB EXPLORERS VISIT MANY CLIMES

JANUARY, 1927 -

Article

ArticlePosthumous DSC

December 1945 -

Article

ArticleReading List

Mar/Apr 2007 -

Article

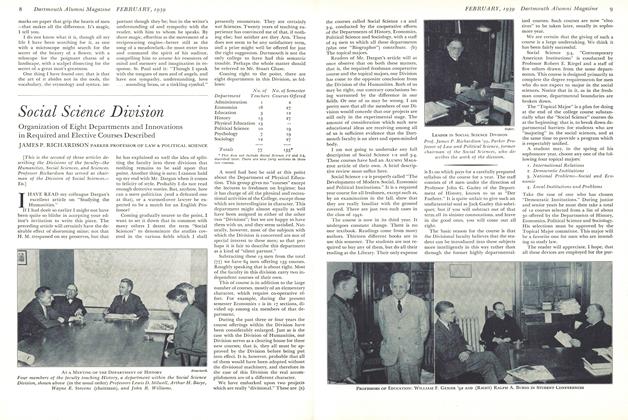

ArticleSocial Science Division

February 1939 By JAMES P. RICHARDSON -

Article

ArticleClass of 2002

July/August 2008 By Lauren Smith '08 -

Article

ArticleNot So Long Ago

October 1934 By R. M. Pearson '20