THE DISEASE is not merely a future danger; it is prostrating Hanover already. A committee should be formed. The threat must be met. Doctors from the Clinic, though busy, must be drafted. Yet it ought to be stated in fairness to all, especially to the young who are more susceptible than the middle-aged and elderly, that even the best medical thought shows resignation, even despair, at the prospect of doing much about it.

The first symptoms are restlessness, a flush in the cheeks, and a disinclination for regular study. Mild claustrophobia develops in Baker Library. Laboratories seem overheated and unbearably odoriferous. Patients need to lean out of dormitory windows. They feel an urge to snuff up air, though it smells damply of wet soil. They seem to enjoy daydreaming more than anything. Indoors they are hot; outdoors they are cold; they sit in the sun and shiver with hot-cold sensations. A tight feeling about the chest drives many into fields and woods around Hanover where some experience heart pounding, a noxious symptom in a variant known as nympholepsy. Mornings they lie abed; afternoons they stumble about Velvet Rocks; evenings, listening to peepers they meander mooningly about faculty Pond or on the golf links they stare up uncomprehendingly at the skijump monstrosity.

It is small comfort to realize that the symptoms are radically different from those present in trypanosomiasis since treatment with the derivation of chaulmoogra, hydrocarpus oil, cannot be used in incipient cases with much hope of cure. A different kind of oil is necessary as balm for hearts troubled with Febris Aprilis. Indeed, as epidemiologists point out, primary and secondary factors work in a way that cause individual sufferers to show different manifestations according to age, sex, relative immunity, climate, and other conditions. (Medicine is an exact science, and doctors love to give precise answers.)

To alarmists one may say that the aisease ease is not of recent or of local origin. A volume of the Medieval Library edited by Sir Israel Gollancz records that students in the Middle Ages showed:

continual waking, moving and casting about the eyes, ranging, stretching and casting out of hands, moving and wagging of the head, grinding and gnashing of the teeth; always they will rise out of their bed, now they sing, now they weep.

For such fever sufferers doctors prescribed a treatment no longer used in Dick's House:

The medicine is that in the beginning the patient's head be shaved and washed in lukewarm vinegar and that he be well kept or bound in a dark place . . . The temples and forehead shall be anointed with the juice of lettuce or of poppy.

If within three days this medicine did not work, doctors gave up in despair.

In the Renaissance the medical profession handled feverish students differently. Acting on the belief that four fluids called humors—blood, phlegm, choler (yellow bile), and melancholy (black bile)—formed a man's constitution, they would probably offer the following diagnosis for HanoverPlain fever: excess or morbidity of one humor. So a moping student would be cupped (i.e. bled) or fed drugs to reduce the peccancy (i.e. excess humor). Afterwards he would feel better if improvement were measured by a diminution of energy.

In the Eighteenth Century, so restlessly unwilling to study and so feverish in the spring were students that many took the best remedy known to the times, Dr. James's Fever Powder. It consisted of antimony and phosphate of lime, a pernicious remedy because it was a depressant. It was nevertheless frequently prescribed as a febrifuge at any time that a patient felt hot, whether he had fever or not. Dr. Johnson was a friend of Dr. James; Horace Walpole praised the medicine; and Oliver Goldsmith may have died of it. Students did not much like it because it cost half a crown.

We can be thankful that Hanover doctors are sounder. The strain of an operation performed in the eighteenth century without anasthesia was so great on educated surgeons that Dr. John Abernethy, to mention only one, rarely undertook a

serious operation without vomiting. Dr. Joanna Stevens, a female, persuaded Parliament to give her 5,000 pounds for her medicine which she said would dissolve or rid a person of calculous concretions in the kidney, bladder, or gall bladderstones people called them. Analyzed, the drug consisted of a powder of calcined egg shells and snails; a decoction of soap and swine's-cress, an herb that smelled like a pig farm; and pills made with honey to make them taste sweet with the addition of snails and soap to make them potent. Sir Robert Walpole, the great British Prime Minister, believed so devoutly in this treatment that modern doctors calculate he ate 180 pounds of soap and drank 1,200 gallons of lime water before he died.

Outing Clubbers rarely have Febris Aprilis like the hothouse boys who lie around in dormitories listening to bebop and getting their blood all stirred up by irregular rhythms. Chubbers are strong for the regular rhythms of seasons. Spring means drinking maple sap out of Vermont buckets and the smell of outdoor vats where it is being boiled down to sugar. In this most bizarre of winters, incidentally, farmers began sugaring the third week in February, and some robins suffering from an ornithological Febris Aprilis returned from the South before March and gave quizzical looks at chickadees, chipper even in zero weather, as if to say, "You little fellows don't look so rugged. How do you do it?" Hanover bird stations were cleaned out by the handsome greediness of evening grossbeaks, absent last year and present this, whose politeness to one another about sunflower seeds at their arboreal dinner tables could hardly be sanctioned in the Jenny Wren Book of Social Etiquette. Fortunately robins prefer steak dinners of worms, but such meat in February seemed beyond the reach of those with bills.

And spring means corn snow on Tuckerman and Tremblant. Though Dartmouth skiers, sleeves rolled up and bare-headed, return from there with faces suggesting acute scarlet fever and chronic alcoholism, their blood runs cool and pure.

Loss of appetite and neurotic self pity, signs of the April disease, rarely appear in those undergraduates who go to hums on the Campus and let sounds come forth from uninhibited vocal cords. Emitting what savage heads believe is mellifluous music, savage breasts are calmed.

What of Bermuda? This piece is written before the return of those who tried to let the sun cook out their restlessness on island sands and to let the tinkle of cocktail ice and the tinkle of Wellesley and Smith laughter at dances put it right back in. It is difficult to know whether a man can achieve balance in Bermuda by becoming a sun worshipper by day and a moon worshipper by night. One may doubt whether if that balance can be brought back to Hanover, it will outlast the bar-and-beach tan.

Talk of spring without baseball? What is Bermuda with exotic blisses (if exotic and blisses are the right words) compared to the native joys of baseball, the crack of leather on wood and the almost instantaneous cries of delight and pain during fraternity games on the campus? To outsiders, nature's plumes, the Hanover elms, are more exotic than palms. Indigenous enough, professors and students stand about, watching, their feet weaving irregular patterns against the senior fence.

In fraternity houses, there is happy talk of happy futures. Hungry men go to supper, lips welcoming the long evenings with whistling more or less off key, cheerful in blues discordancies.

Dormitories, yellow with friendly light, grow warm with talk that is cooled with beer. The Tower Room is filled with potential fever victims warding off attack by reading novels and travel literature. The hiding places in the stacks show pale faces and notebooks filled with information useful for examinations and often enough useful for life. These serious seekers of knowledge may be the next victims.

The name some persons give to Febris Aprilis is Spring Fever. It is an insidious disease. It strikes where least expected. It causes the bodies of old professors to shiver; they had thought that they were immune and had thanked God. A Phi Bete student who in no way resembles the Orozco caricature of him in Baker throws his books away in disgust and is prepared to take a rotten little C on tomorrow's quiz. Joseph Wunnate goes all to pieces; he hasn't strength enough to do more than slump down in his chair and look at the outside of that text talking gibberish about economics. "Money isn't everything," he tells himself unconvincingly.

Yes, let no one gloss over the facts that Spring Fever has come along with April and that it is prostrating Hanover. Few Dartmouth graduates, however, would recommend that a committee be formed. Let the doctors return to their Clinic. Graduates know that there is no danger from Spring Fever in Hanover. In other college towns it might be deadly and action taken to legislate against it.

Out in what is usually referred to as the cold, cold world, where seasons become matters of indifference, Dartmouth men with degrees testifying to their wisdom feel a sudden glow at the mention of Spring Fever. They themselves are not coming down with it, but they wish that they were. To sons who write home that they are prostrated with it and that college work is suffering, fathers who have been smitten many years ago feel as though they would like to wire:

Congratulations. Spring Fever part ofyour education. Studies not everything. Check for $l00 follows.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Article

ArticleTHE ARCTIC

April 1949 By TREVOR LLOYD, -

Article

ArticleConcerning Admissions

April 1949 By H. CLIFFORD BEAN '16 -

Lettter from the Editor

Lettter from the EditorLetter from Oxford

April 1949 By CHARLES G. BOLTE '41 -

Class Notes

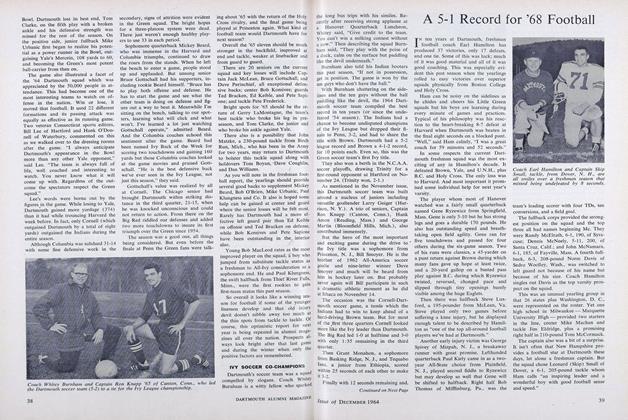

Class Notes1918

April 1949 By ERNEST H. EARLEY, DONALD L. BARR, RICHARD A. HOLTON -

Article

ArticleDeaths

April 1949 -

Class Notes

Class Notes1929

April 1949 By F. WILLIAM ANDRES, EDWIN C. CHINLUND, GEORGE B. REDDING

Article

-

Article

ArticleA 5-1 Record for '68 Football

DECEMBER 1964 -

Article

ArticleCalling all art collectors

MARCH • 1986 -

Article

ArticleDr. Wheelock's Journal

December 1989 -

Article

ArticleSHORT AND SWEET

DECEMBER 1930 By A. I. D. -

Article

ArticleCutter Triumph: A Thinking Man's Cabaret

MARCH 1966 By L.G. -

Article

ArticleTales Out of School

October 1995 By Stanley Williams Ph.D.'83