If one were to ask the pretty little student wife who is making a wide red leather belt, or the football player over in the corner who is muttering imprecations at a particularly obstinate piece of wood, or the Rufus Choate scholar contemplating a mitred and keyed joint with satisfaction, or the dozen other individuals scattered about the Student Workshop, why they enjoyed doing what they were doing the answers would be as varied as they were true.

The most obvious satisfaction derived from woodworking and the allied arts is found in the attainability of the goal. This is not to say that the construction of a cabinet or a bookcase can serve as a sop to the contemporary cultural frustration, but it can act in a stabilizing fashion, offering to the builder something concrete in exchange for the energy expended.

There is a creative urge in every individual which cannot usually be realized through the highly developed artistic forms, which in the workshop results in the metamorphosis of the sonnet into the spice box. There is a genuine therapeutic value in this substitution—a soothing balm for ragged nerves—a recognition for the self that the fingers were fashioned for other uses than clutching-culinary implements or making marginal notations.

There are other things too, more subtle, more poetic if you will. There is the unique smell of each type of wood—the dusty dry musty odor of an old piece of black walnut, or the acrid, pungent odor of a piece of white pine, not yet quite dry, as they go through the planer—or the planer itself as it sucks in a piece of wood, like a novice eating spaghetti, with a slow steady whine which suddenly alters drastically in pitch and steps into a shrill shriek as the whirling blades strike a knot in the surface of the wood. Then there are shavings—long, waxy soft pine shavings curving up out of the hand plane around your wrist—curly shavings that as a child your sister used to wear in her hair and deem herself a fit lady for any knight. They looked rather nice, you thought.

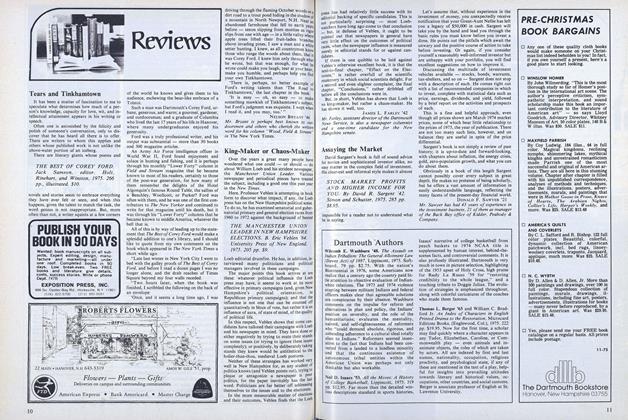

There is camaraderie among the woodworkers, too. Solid friendships spring up out of the mutual-appreciation period at the end of the day when everyone stands back and contemplates his work and the work of others, and if here and there there is a blemish, or a shelf a little out of line, the eagle eye of Virgil Poling, the workshop's mentor, will discover it, and the defect will be remedied before the work leaves the shop, for the otherwise equitable Mr. Poling is adamant on this score, and deems perfection attainable.

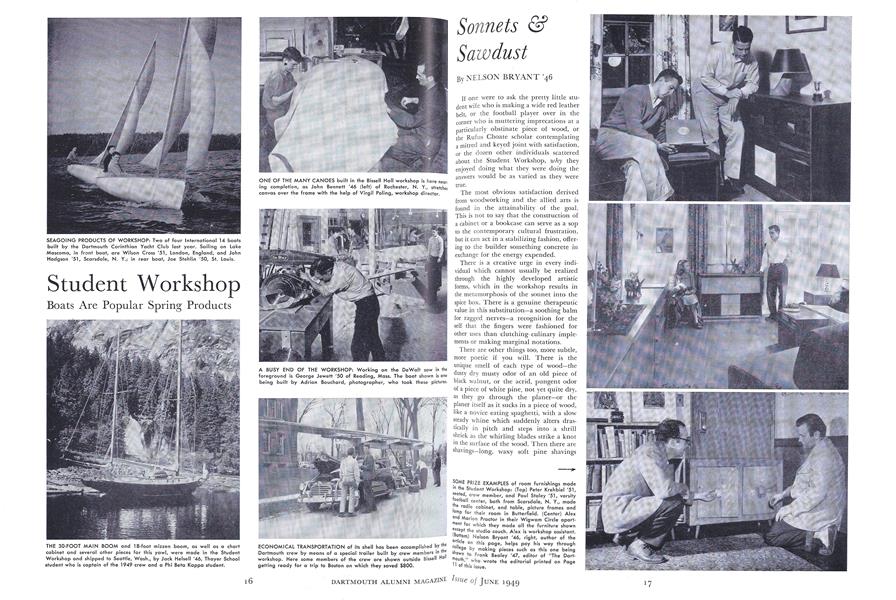

In the spring when people are speculating as to the last snow, and windows are being thrown open during the warmest hours of the day and the smack of a baseball into a mitt may be heard, romance enters the workshop. The tempo seems to slacken, and a new species of handicraft comes into existence. Boats—from ninefoot cartop dinghies to sixteen-foot sea skiffs they spring into being like mushrooms on the east pasture. There are trail canoes and work canoes, International Fourteens and various other sailboats of a less thoroughbred class, and traversing the entire shop is the gleaming length of a hollow boom built by Jack Helsell '46 for his Pacific coast yawl. This urge is an old urge and a good urge—and its manifestation in the workshop guarantees that during the following summer there will be at least a few who will be genuinely enjoying the benefits of their labor.

There are other things, which are peculiarly Dartmouth: the rush of damaged skis to be repaired in the winter which is followed in the spring by Tom Dent's tribe of lacrosse men fashioning their new sticks to suit themselves and not the manufacturer. Or there is Tom himself expending the labor of love on a birdseye maple cabinet and singing incessantly and not without some feeling about "Far Away Places."

So it develops that the pretty little student wife and the football player and the Rufus Choate scholar and the freshman, sophomore, junior, senior are not going to enjoy only the results of their efforts but the effort itself, and this truth is one step away from being profound. To find satisfaction in the means to an end as well as the end itself is to have achieved a remarkably well adjusted life. Even though this type of work represents only a very small portion of the average individual's activities, it is important in just the degree that it offers satisfaction and freedom from the restraint and hurly-burly of everyday existence which places so much importance on the ends, on the acquisition of artificiality and artifacts, rather than on a congenial way of living. Sonnets and sawdust represent a partial solution to the problem.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Article

ArticleMusic at Dartmouth

June 1949 By ANDREW L. PINCUS '51 -

Class Notes

Class Notes1918

June 1949 By ERNEST H. EARLEY, DONALD L. BARR, RICHARD A. HOLTON -

Article

ArticleSalmon P. Chase

June 1949 By EDWARD C. LATHEM '51 -

Class Notes

Class Notes1897

June 1949 By WILLIAM H. HAM, MORTON C. TUTTLE -

Class Notes

Class Notes1937

June 1949 By ROBERT C. BANKART, ARTHUR H. RUGGLES JR., ALAN W. BRYANT -

Class Notes

Class Notes1926

June 1949 By E. PAUL VENNEMAN, HERBERT F. DARLING, ALBERT E. M. LOUER