THE purpose of this article is simply to survey the musical activities at Dartmouth. Because the scope of this topic is greater than the casual reader might suspect, the writer has not gone into great detail, but has held more or less to a descriptive analysis. The Handel Society, a joint college-community organization of 150 members, represents by its large membership, active participation in concerts, and genuine musical spirit, perhaps the highest point of musical activity in Hanover. Therefore, a few of the more pertinent details in the Society's past and present have been given, somewhat by way of a personal tribute to the important role the Society has performed in providmg the musical momentum of the community.

In 1787, not long after the time when Dartmouth's most important link with the musical world was a now-legendary drum, a spontaneous student-community organization was formed for the purpose of spreading the sacred choral music of the preceding century. To this group's eventual chagrin, it also happened that at this time Europe was the scene of a rev-0 ution against the Classicism which this anover organization so admired. As a result, the newly-formed group found itwhich face t0 aCe w't'l "radical" elements ch were contaminating musical " purity." In 1807 the situation had become so intolerable to these self-appointed saviors of music that, throwing caution to the winds (and leaving the rest of the orchestra to shift for itself), they organized The Handel Society of Dartmouth College to combat such heretical musical trends. Their counter-revolution's avowed objectives were "to improve and cultivate the taste, and promote true and genuine music and discountenance trifling, unfinished pieces."

The fledgling Society had its ups and downs, but managed to amass a fair-sized library of sacred music for its rapidly growing chorus and a few assorted musical instruments for the beginnings of its orchestra. A moment of drastic action came in 1838, however, when the Society's administrative committee decided to mix some of the "radical" secular music of the day into the Society's sacred repertoire. The result of this drastic move was that two members of the committee resigned in outright disgust.

The Handel Society has survived such temporary setbacks as this, and exists today as a very active campus organization, filling what would otherwise be a large void in community activities. The Society was reorganized in the early 1920's by Prof. Maurice F. Longhurst after a rather lengthy period of inactivity, and the organization continues to grow, year by year. Prof. A. Kunrad Kvam, who just recently took over the reins of the Society, now conducts the 100-voice mixed chorus and 50-piece symphony orchestra in its frequent appearances around the community.

The Handel Society is actually a community project, for it draws about equally from the student body, faculty, and community at large for its personnel. Time now has tempered the Society's harsh feelings toward certain "radical" composers whose music was "trifling and unfinished."

So tempered are their feelings, in fact, that the orchestra has seen fit to play one of the "unfinished" pieces—Schubert's famous symphony, of course—on one of the four programs it has presented in Webster Hall this year. The occasion of this symphony's performance was the orchestra's annual spring concert, a full-length symphonic program which also included music by the esteemed Haydn and by a power with whom the original Handelians never had to contend—Tchaikovsky. Earlier in the year the orchestra presented its annual concerto program. This program, which consisted this year of two concerti each by Bach and Mozart, always features soloists drawn mostly from the student body and the community.

With 142 years of tradition behind it, the Handel Society is not one to eliminate the tradition which accompanies such a venerable age. Twice this year the chorus has joined the orchestra under the scowling portrait of Daniel Webster in the building which is now his namesake to pay homage to seventeenth- and eighteenthcentury sacred music. These two performances took the form of oratorios by Handel (The Messiah) and Haydn (The Creation).

Indicative of a generally high degree of musical interest and activity in and around Dartmouth, these programs attract large audiences, whose enthusiasm is almost chauvinistic in its intensity. This enthusiasm does not end with the zealous applause which follows Handel Society programs, but is further extended to form a protective element for the Society, defending it from critical bludgeonings which, are administered occasionally by local writers.

Musical interest at Dartmouth does not simply take the passive form of concert attendance. With enthusiasm that overcomes technical obstacles, many instrumental and choral groups of varying sizes and shapes have found their inspiration in college-sponsored musical activities and facilities. One of these groups is the Dartmouth String Quartet, a self-perpetuating ensemble which draws from the best instrumentalists in the College and community for its regular personnel and guest artists. As a group and as individuals, this organization has been directly responsible for many outstanding programs of chamber music since its formation two years ago.

More impromptu in conception are the numerous all-student groups which gather to play music for their own pleasure and satisfaction. Some of these have proven to be of such quality that they have appeared —as both groups and individuals—in recitals.

Another such impromptu group is Prof. Frederick W. Sternfeld's madrigal group, a fourteen-voice mixed chorus which devotes itself exclusively to the neglected music of the Renaissance era. This group performed for the New England Renaissance Conference at its meeting in Hanover this spring.

More widely known because of the wanderlust which yearly incites it to tour the hinterlands, the Glee Club is one of the most active of all student organizations. Under the direction of Mr. Paul R. Zeller, this übiquitous group of greenjacketed undergraduates provides entertainment for both the student body and the alumni (as many nostalgic alumni can testify after the annual spring tour). The Glee Club's frequent Hanover appearances include concerts at Carnival, Green Key, and Houseparty weekends and the more spontaneous appearances at football rallies.

Distinctive in its collegiate informality, the band has proven itself to be as versatile as it is popular. Under the baton of Mr. Francis E. Lawlor, the band has appeared in concerts (not to mention football game pageants) in Hanover and around New England. The band, however, is famed for its charity, for it gives that dying old gent, vaudeville, a shot of adrenal slapstick every spring at the immensely popular Variety Night in Webster Hall.

There are still other musical ensembles at Dartmouth, and several of these take the form of popular and dance bands. After a period of war-time hibernation, the Barbary Coast Orchestra recently poked its short-maned head out of its hole, saw no shadow, and decided to stay. Generally, it has stayed, but weekends often find it pumping out dance rhythms around the countryside.

WDBS, the student-run disc-jockey emporium, provides a great deal of the music which is constantly heard eddying and swirling around the dormitories. Canned music forms a large part of the programs the station puts on to satisfy the variety of tastes to be found on campus. The nightly Symphonic Hour has presented some programs of particular interest, featuring series on great composers and musical epochs. In lighter vein, one 0f WDBS's more popular attractions is the program, "Guest Performance," which utilizes student talent as much as possible Pianists, small combinations, and fujj_sized popular bands have appeared on this show.

Musical interest manifests itself in many other (and sometimes quite peculiar) ways at Dartmouth. For example, The Dartmouth's "Vox Populi" column this year was the unwilled medium of an extended dispute on the relative merits of contemporary music and the standard classics (shades of 1807!). The air was thick with high-explosive opinions, some of which fizzled out as an innocuous puff of tepid air, others of which rent the skies with screaming epithets. Squaring off at each other, the belligerents profaned practically every composer who ever so much as dared to put a few notes on a piece of ruled paper before the feud was ended by Christmas vacation. There was the enlightening revelation that "such hacks as Mozart. Bach and Beethoven" had been composing "small stuff" and "decadent, reactionary, dry, monotonous, sterile clap-trap" all along. Another pearl of wisdom was keynoted by the valiant proclamation that "[certain persons] cease trying to perpetrate modernism on us under the guise of music."

Local record stores, second in popularity only to the time-honored Saturday night movie, are grottos for music-lovers of all breeds and cross-breeds (not to mention a few downright mongrels which periodically show up). As such, record sales are a good indicator of musical interests. The Music and Recording Studio's Harry (often said to be short for Harrassed) Gerry, the genial and (sometimes) sympathetic purveyor of music and uninhibited opinion, will readily attest to the fact that Dartmouth's musical tastes are diverse. Significantly enough, Harry reports that classical outsells popular by a ratio of better than two to one, with Le Jazz Hot simmering down into a lukewarm third.

Local musical society turns out in its best form for the programs on the concert series. Over the past few years, such great names as Artur Rubinstein, Helen Traubel, Isaac Stern, Erich Leinsdorf, and Robert Shaw have graced Webster's boards. This year's concert series featured two symphony orchestras—the Baltimore and Rochester—and two pianists, Gunnar Johansen and Theodore Ullman. The Robert Shaw Chorale and Leonard dePaur Infantry Chorus gave choral concerts, while the anomalous haranguings and gesticulations of Iva Kitchell were billed as "ballet satire." These concerts are continually rotated with alternate music forms so that Hanover will get a balanced musical diet over the years.

The 1600 persons who invariably bin out Webster Hall for these concerts represent only a fraction of those who woul like to hear them. And, of those who do gain admission, only local music critics can find any use or the building's abominable acoustics. (The critics take great delight in shelling something with unprotested critical brick-bats.) Webster Hall, apparently ashamed of the crass reality of this situation, disguises itself as "The Nugget" at all times other than concert nights, thus minimizing available rehearsal time in the building.

The College Music Department itself ;s housed in medieval-looking (and sounding) Bartlett Hall, which was built in 1893 to be the bastion of the now-defunct Hanover Y.M.C.A. The inadequacy of this building is simply a matter of self-evident truth, and the dissonance sounded by those who protest this unfortunate situation (and there are many who do protest) will not be resolved until the Hopkins Center hatches from its incubational period.

Strangely enough, however, certain ha-Ijituis of Bartlett profess a fraternal fondness for the old fort. Their claims to the advantageousness of the building center around a faithful steam-pipe which unerringly sounds middle A (the perfect tuning pitch) whenever the steam is cut on. (Even these persons admit to the nuisance of the continued racket after the pipe has served its usefulness.) But these same persons may be heard singing praises of the unusual contrapuntal effects achieved when two or more practise rooms are in use simultaneously (for sound-proofing is a myth in Bartlett).

To most Bartlettites, such advantages as these are questionable, to say the least. That is why the glass facade of Hopkins Center gleams like an ivory tower to so many beleaguered frequenters of Bartlett Hall. It would be mere repetition, of course, to tell an alumni audience about the need for the new Center, so let it rest by saying that the Music Department, its clientele, and all Dartmouth and Hanover look forward to the day when that first shovelful of Hanover mud is hoisted.

The Music Department, incidentally, is one of the most active and rapidly expanding departments in the College. Through the efforts of Professor Kvam, its chairman, the Music Department is offering a complete major course of study in music this year for the first time in department history. Other members of this progressive department's staff include Professors Longhurst and Sternfeld and Messrs. Zeller and Lawlor.

Also unique in Music Department history are the two Associate Artists introduced this year in connection with the new music major. Mrs. Lydia Hofmann-Behrendt, a concert pianist who is well known in Hanover through her frequent performances, and Nathan Gottschalk '49, a violinist whose abilities won him a position as assistant concert-master of the Pittsburgh Symphony Orchestra before his years at Dartmouth, and who has subsequently become another frequent performer in local concerts, were this year's Associate Artists. (Hanover music society will certainly regret the loss of Mr. Gott- schalk, who graduates with his class this month.) In addition to giving instruction on their respective instruments, these Associate Artists are very active members of the Dartmouth String Quartet and other local musical groups. For students interested in instruction on instruments other than violin and piano, instruction on almost every standard instrument is available through qualified members of the faculty and community.

The Department's courses are varied to suit the needs and interests of all students. For the student interested primarily in an introduction to intelligent listening, Professor Sternfeld's introductory course is both informative and popular. This course induces some 175 students per semester to pass through Bartlett's doors.

For the student interested in technical training, thorough instruction is available in theory, harmony, composition, and orchestration. Other specialized courses offer research into the fields -of music history (including a seminar), modern music, and the Wagnerian era. Of particular interest to many music students is Professor Sternfeld's course on dramatic music, for this is the unusual course which studies—in addition to the usual academic fields of opera and ballet—the dramatic music which is eminently a product of this century, movie music. This course utilizes the College's collection of movie scores, which is the largest collection outside of Hollywood itself, and the English Department's large collection of movie scripts.

All these activities reflect the fact that Dartmouth, already very musical, is becoming more and more so. Dartmouth musicality is so inherent that it is subconscious and thus often taken for granted. This article has hardly touched upon the many aspects that this inherent musicality takes in its more spontaneous forms: dormitory and fraternity song fests, the fraternity hum, the ever-present whistle °f the student as he walks across the campus, the college spirit as evidenced through exuberant singing at the pep rallies. It is the musical spirit thus manifesting itself that has made the Dartmouth community an important musical center 111 its section of New England.

MUSICIAN-AUTHOR: Andrew L. Pincus '51 of New Orleans, who wrote this musical survey, is a pianist and does reviews for the Hanover weekly.

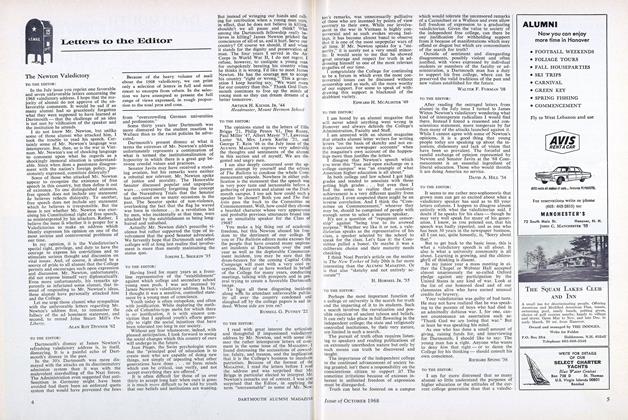

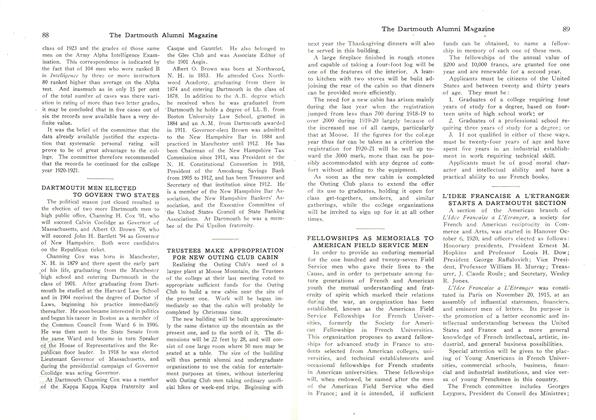

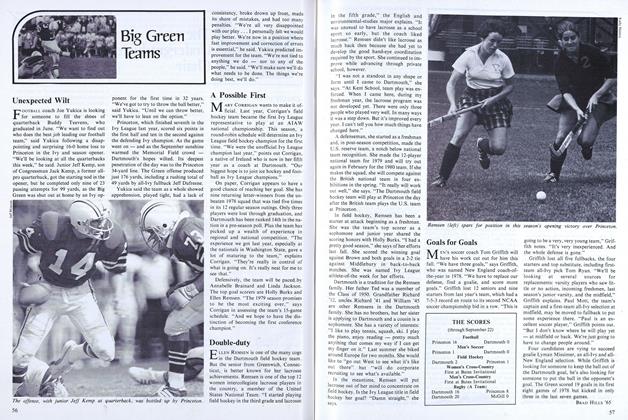

SYMPHONY REHEARSAL: Preparing for its big annual concert, the 50-piece Handel Society Symphony Orchestra of students, faculty and townspeople holds a night rehearsal with Professor Kvam conducting.

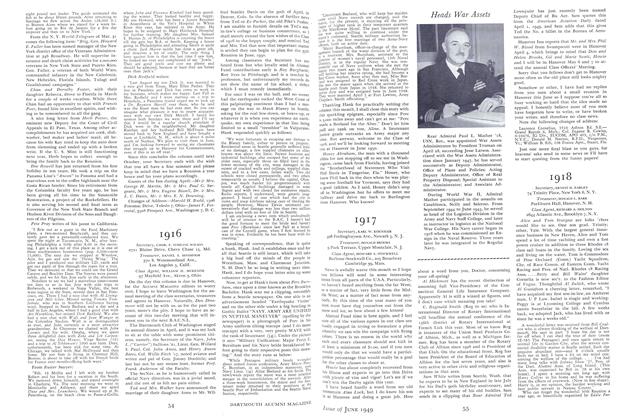

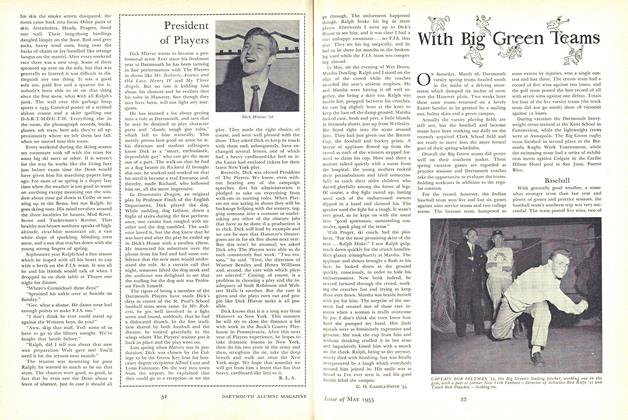

DARTMOUTH'S MUSIC FACULTY, on the steps of Bartlett, includes (I. to r.) Paul R. Zeller, who also directs the Glee Club; Prof. Frederick W. Sternfeld; Prof. Maurice F. Longhurst, senior member of the department; Francis E. Lawlor, who also directs the Band; and Prof. A. Kunrad Kvam, department chairman.

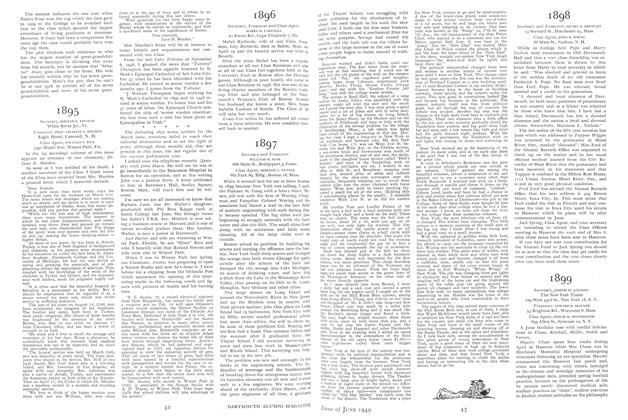

BARTLETT HALL ACTIVITIES: Left, an informal student trio plays together for the fun of it. Shown (I. to r.) are Nason Hurowitz '51, John Condit '46 and RobertMaguire 51. Right, students from one of the music classes use earphones to listen to a symphonic recording while following the printed score.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Class Notes

Class Notes1918

June 1949 By ERNEST H. EARLEY, DONALD L. BARR, RICHARD A. HOLTON -

Article

ArticleSalmon P. Chase

June 1949 By EDWARD C. LATHEM '51 -

Class Notes

Class Notes1897

June 1949 By WILLIAM H. HAM, MORTON C. TUTTLE -

Class Notes

Class Notes1937

June 1949 By ROBERT C. BANKART, ARTHUR H. RUGGLES JR., ALAN W. BRYANT -

Class Notes

Class Notes1926

June 1949 By E. PAUL VENNEMAN, HERBERT F. DARLING, ALBERT E. M. LOUER -

Article

ArticleThe Undergraduate Chair

June 1949 By Robert L. Allcott '50

ANDREW L. PINCUS '51

Article

-

Article

ArticleMAGAZINE OF VERSE PROPOSED AS NEW COLLEGE PERIODICAL

December 1920 -

Article

ArticleMagazine Circulation

December 1938 -

Article

ArticleThe Alumni Council for 1973-74

October 1973 -

Article

ArticleA Possible First

October 1979 -

Article

ArticlePresident of Players

May 1955 By R.L.A. -

Article

ArticleGRADUS AD PARNASSUM

May 1941 By The Editor