THE UNDISCOVERED COUNTRY by Professor John Hay Norton, 1982. 192 pp. $12.95

There are few who examine the natural world with such probity and talent as John Hay, whose latest book, The Undiscovered Country, is an utter delight.

Hay first netted me with The Run, a chronicle of the annual spring spawning ritual of alewives or herring, as they are more commonly called along the New England coast. He has written extensively and eloquently about that fragile coastal country, and about a decade ago Dartmouth sensibly invited him to be a visiting professor of environmental studies and English.

Admittedly an amateur albeit highly informed in natural science, Hay's particular gift is his ability to take his own discoveries and those of the professional biologists and, so provisioned, to journey far beyond those individual bits of information.

In his introduction to The UndiscoveredCountry, he observes, "We may not know ourselves well enough to understand why we behave the way we do, but we receive the universe directly. The surest way ahead is to trust the primal source that each life, human or non-human, embodies. Coexistence requires love, and at the very least an acknowledgement that we do not live in isolation. The exploration has hardly started."

Man's special glory and burden is that he can continually strive and often rejoice even though, as with no other species, the dark shadow of his own end is always present, whether grinning at his shoulder or lurking in the valley ahead.

"For all our dam building against nature," Hay writes, "we can hardly avoid sensing its inevitable processes in ourselves. We know that the artificial lengthening of our days fails to cheat death. We know that nothing stops deterioration in our bodies or our machines. What else could bring us, all the same, to mutual love and need, but this universal inclusion? Accept the endless eggs and seeds for their immortal habit, in which we are equal with the frogs, the flies, the plankton and the pine. No life under the sun is inferior to that of the human species."

Every creative man plants a special garden. Some write poems, some shape beautiful objects from wood and stone, some transform the music of the spheres into sounds and cadences audible to ordinary ears, and many more falter and leave the garden half-filled with desiccated dreams that weeds of weariness and doubt have overwhelmed.

Sustained by wonder and humility, John Hay has tended his garden well.

There is, as previously suggested, an abundance of deft and fascinating observations of the natural world in Hay's book: the species of freshwater mussel that times its spawning with that of the alewife so that the larvae of the former may attach themselves to the latter for three critical weeks of growth before dropping off— the three weeks that the alewife remains in fresh water; the burst of birdsong that comes just before dawn, then dies away until the sun has truly risen.

The Undiscovered Country is a marvelously felicitous and joyous account of mans realization that we do not dance alone.

Nelson Bryant writes a column about the outdoors for the New York Times.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

Feature'Far Out and Daring': Dartmouth Abroad

September 1982 By Shelby Grantham -

Feature

FeatureFIRST IN THE EYES OF HIS COUNTRYMEN

September 1982 By David Shribman -

Class Notes

Class Notes1957

September 1982 By Daniel M. Searby -

Article

Article"Man Better Man"

September 1982 By Nardi Reeder Campion -

Sports

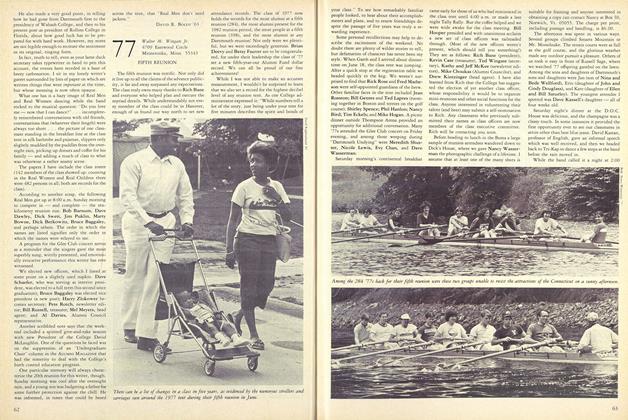

SportsHelp Wanted: Rising Sophomores

September 1982 By Brad Hills '65 -

Class Notes

Class Notes1977

September 1982 By Walter M. Wingate Jr., Lindsay Larrabee Greimann '77

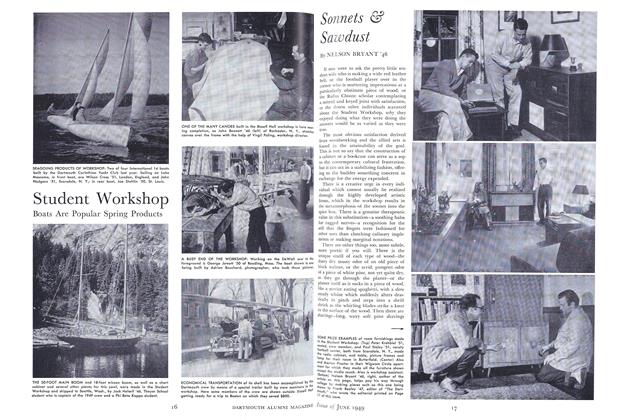

Nelson Bryant '46

Books

-

Books

BooksThe Great Technology, Social Chaos and the Public Mind

May 1933 -

Books

BooksAlumni Articles

March 1956 -

Books

BooksAlumni Articles

December 1956 -

Books

BooksPORTUGUESE AFRICA.

JANUARY 1968 By CHRISTIAN P. POTHOLM II -

Books

BooksTHE STORY OF MOUNT WASHINGTON.

June 1960 By STEARNS MORSE -

Books

BooksAMERICAN PENMANSHIP

JULY 1970 By TRUMAN H. BRACKETT JR. '55