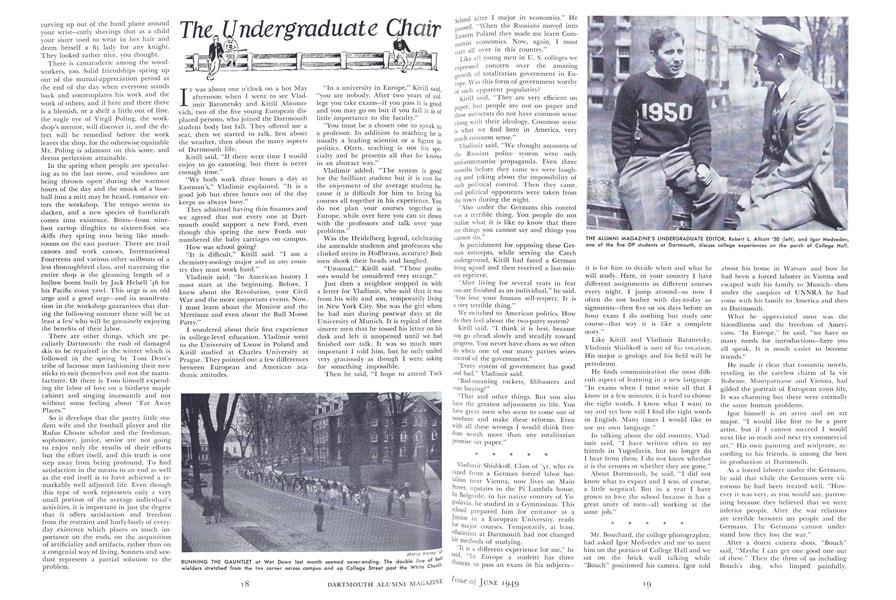

IT was about one o'clock on a hot May afternoon when I went to see Vladimir Baronetsky and Kirill Abromovich two of the five young European displaced persons, who joined the Dartmouth student body last fall. They offered me a seat, then we started to talk, first about the weather, then about the many aspects of Dartmouth life.

Kirill said, "If there were time I would enjoy to go canoeing, but there is never enough time."

"We both work three hours a day at Eastman's," Vladimir explained. "It is a good job but three hours out of the day keeps us always busy."

They admitted having thin finances and we agreed that not every one at Dartmouth could support a new Ford, even though this spring the new Fords outnumbered the baby carriages on campus. How was school going?

"It is difficult," Kirill said. "I am a chemistry-zoology major and in any country they must work hard."

Vladimir said, "In American history I must start at the beginning. Before, I knew about the Revolution, your Civil War and the more important events. Now, I must learn about the Monitor and the Merrimac and even about the Bull Moose Party."

I wondered about their first experience in college-level education. Vladimir went to the University of Lwow in Poland and Kirill studied at Charles University at Prague. They pointed out a few differences between European and American academic attitudes.

"In a university in Europe," Kirill said, "you are nobody. After two years of col- lege you take exams—if you pass it is good and you may go on but if you fail it is of little importance to the faculty."

"You must be a chosen one to speak to a professor. In addition to teaching he is usually a leading scientist or a figure in politics. Often, teaching is not his spe- cialty and he presents all that he knows in an abstract way."

Vladimir added, "The system is good for the brilliant student but it is not for the enjoyment of the average student because it is difficult for him to bring his courses all together in his experience. You do not plan your courses together in Europe, while over here you can sit down with the professors and talk over your problems."

Was the Heidelberg legend, celebrating the amenable students and professors who clinked steins in Hoffbraus, accurate? Both men shook their heads and laughed.

"Unusual," Kirill said. "Those professors would be considered very strange." Just then a neighbor stopped in with a letter for Vladimir, who said that it was from his wife and son, temporarily living in New York City. She was the girl whom he had met during postwar days at the University of Munich. It is typical of these sincere men that he tossed his letter on his desk and left it unopened until we had finished our talk. It was so much more important I told him, but he only smiled very graciously as though I were asking for something impossible.

Then he said, "I hope to attend Tuck School after I major in economics." He used. "When the Russians moved into Eastern Poland they made me learn Communist economics. Now, again, I must start all over in this country."

Like all young men in U. S. colleges we expressed concern . over the amazing arowth of totalitarian government in Europe. Was this form of government worthy of such apparent popularity?

Kirill said, "They are very efficient on paper, but people are not on paper and these autocrats do not have common sense along with their ideology. Common sense is what we find here in America, very much common sense."

Vladimir said, "We thought accounts of the Russian police system were only anti-communist propaganda. Even three months before they came we were laughing and joking about the impossibility of such political control. Then they came, and political opponents were taken from the town during the night.

"Also under the Germans this control was a terrible thing. You people do not realize what it is like to know that there are things you cannot say and things you cannot do."

As punishment for opposing these German concepts, while serving the Czech underground, Kirill had faced a German firing squad and then received a last-minute reprieve.

"After living for several years in fear you are finished as an individual," he said. "You lose your human self-respect. It is a very terrible thing."

We switched to American politics. How do they feel about the two-party system?

Kirill said, "I think it is best, because you go ahead, slowly and "steadily toward progress. You never have chaos as we often do when one of our many parties seizes control of the government."

"Every system of government has good and bad," Vladimir said.

"Bad-meaning rackets, filibusters and vote buying?"

"That and other things. But you also have the greatest adjustment to life. You have great men who seem to come out of nowhere and make these reforms. Even with all these wrongs I would think freedom worth more than any totalitarian promise on paper."

Vladimir Shishkoff, Class of '5l, who escaped from a German forced labor battalion near Vienna, now lives on Main Street, upstairs in the Pi Lambda house. In Belgrade, in his native country of Yugoslavia, he studied in a Gymnasium. This school prepared him for entrance as a Junior in a European University, ready for major courses. Temporarily, at least, education at Dartmouth had not changed "is methods of studying.

"It is a different experience for me," he said. "in Europe a student has three chances to pass an exam in his subjectsit is for him to decide when and what he will study. Here, in your country I have different assignments in different courses every night. I jump around—so now I often do not bother with day-to-day assignments—then five or six days before an hour exam I do nothing but study one course—that way it is like a complete story."

Like Kirill and Vladimir Baranetsky, Vladimir Shishkoff is sure of his vocation. His major is geology and his field will be petroleum.

He finds communication the most diffi cult aspect of learning in a new language.

"In exams when I must write all that I know in a few minutes, it is hard to choose the right words. I know what I want to say and yet how will I find the right words in English. Many times I would like to use my own language."

In talking about the old country, Vladimir said, "I have written often to my friends in Yugoslavia, but no longer do I hear from them. I do not know whether it is the censors or whether they are gone."

About Dartmouth, he said, "I did not know what to expect and I was, of course, a little sceptical. But in a year I have grown to love the school because it has a great unity of men—all working at the same job."

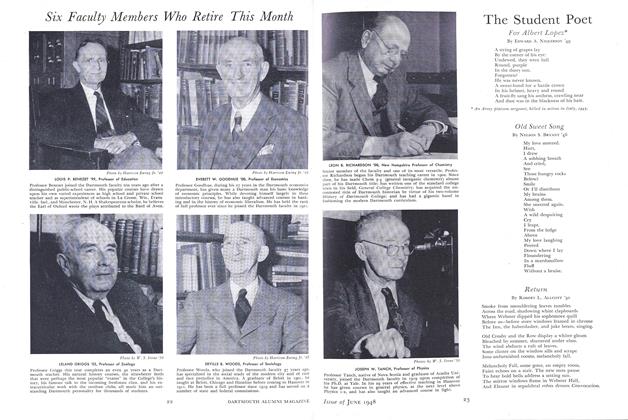

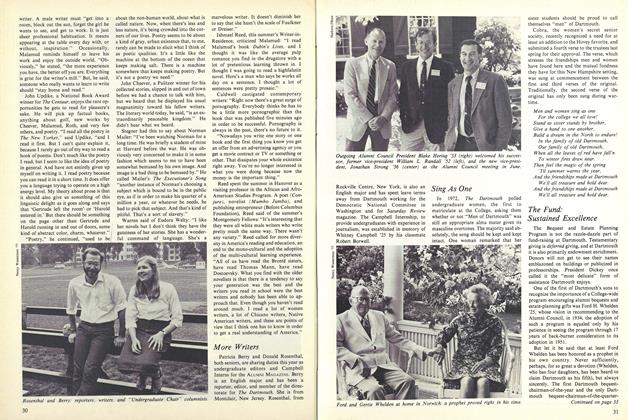

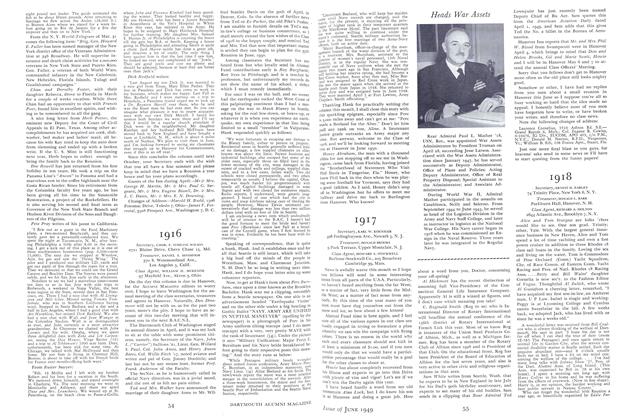

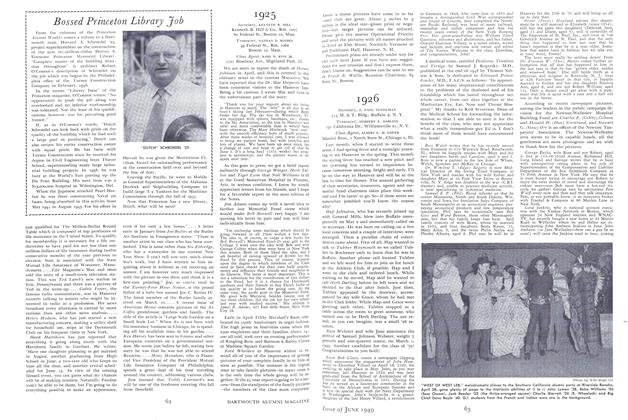

Mr. Bouchard, the college photographer, had asked Igor Medvedev and me to meet him on the portico of College Hall and we sat on the brick wall talking while "Bouch" positioned his camera. Igor told about his home in Warsaw and how he had been a forced laborer in Vienna and escaped with his family to Munich—then under the auspices of UNNRA he had come with his family to America and then to Dartmouth.

What he appreciated most was the friendliness and the freedom of Americans. "In Europe," he said, "we have so many needs for introductions—here you all speak. It is much easier to become friends."

He made it clear that romantic novels, reveling in the careless charm of la vie Boheme, Montparnasse and Vienna, had gilded the portrait of European town life. It was charming but there were eternally the same human problems.

Igor himself is an artist and an art major. "I would like first to be a pure artist, but if I cannot succeed I would next like to teach and next try commercial art." His own painting and sculpture, according to his friends, is among the best in production at Dartmouth.

As a forced laborer under the Germans, he said that while the Germans were victorious he had been treated well. "

However it was very, as you would say, patronizing because they believed that we were inferior people. After the war relations are terrible between my people and the Germans. The Germans cannot understand how they lost the war."

After a dozen camera shots, "Bouch" said, "Maybe I can get one good one out of these." Then the three of us including Bouch's dog, who limped painfully, walked downtown. Bouch was kidding Igor about his cap.

A chance to talk with these four men was a long-anticipated experience for me. It is difficult to reproduce the cadence of their accents but perhaps their comments suggest the hesitant yet thoughtful and intelligent way in which they talk. Of course they would insist that they spoke very bad English but it is really very thorough and polished.

One might expect to find a defeatist cynicism affecting the attitudes of these men who have experienced so much personal insecurity. The opposite is the case. A pessimistic concern for the future is more widespread among men who have never shared the trials of oppressed peoples and struggled for freedom.

In this era of healthy collegiate liberalism, the rare and faint praise of things American is inevitably lost amid the intellectual clamor for Social Justice. In a leisurely collegiate fashion we can dissect the profit and loss system, deride the Republicans and retool the U.S.A. for a new kind of democracy. Our ears ring with the political din.

It was reassuring to listen to men who have lived among the devout admirers of Nietzche and with the modern disciples of Marx—men who can look at the country and Dartmouth College objectively and say, "We like it here."

RUNNING THE GAUNTLET at Wet Down last month seemed never-ending. The double line of belt wielders stretched from the Inn corner across campus and up College Street past the White Church.

THE ALUMNI MAGAZINE'S UNDERGRADUATE EDITOR, Robert L. Allcott '50 (left), and Igor Medvedev, one of the five DP students at Dartmouth, discuss college experiences on the porch of College Hall.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Article

ArticleMusic at Dartmouth

June 1949 By ANDREW L. PINCUS '51 -

Class Notes

Class Notes1918

June 1949 By ERNEST H. EARLEY, DONALD L. BARR, RICHARD A. HOLTON -

Article

ArticleSalmon P. Chase

June 1949 By EDWARD C. LATHEM '51 -

Class Notes

Class Notes1897

June 1949 By WILLIAM H. HAM, MORTON C. TUTTLE -

Class Notes

Class Notes1937

June 1949 By ROBERT C. BANKART, ARTHUR H. RUGGLES JR., ALAN W. BRYANT -

Class Notes

Class Notes1926

June 1949 By E. PAUL VENNEMAN, HERBERT F. DARLING, ALBERT E. M. LOUER