Dartmouth is vitally concerned over a proposed State legislative attempt to curtail academic freedom within its own walls and those of every school in the State of New Hampshire.

House Bill No. 146 and Senate-House Joint Resolution No. 6, proposed by Harold H. Hart, representative from Wolfesboro in the New Hampshire Legislature, stress three educational controls.

First is the establishment of an investigating committee to lay bare the suspected teaching of communist principles; second, the prohibition of the teaching or advocacy of communism; third, the loyalty oath which would be required of teachers.

Dartmouth professors protested immediately, labeling the Hart proposal as a deviation from a commonsense point of view as well as a violation of the Bill of Rights. Prof. George F. Theriault '33 of the Sociology Department summed up the faculty attitude when he said, "I agree with a part of the intent of the provision as I interpret it—that no teacher has the right to advocate overthrow of the government by force.

"I disagree with the statement that no person shall teach the doctrines of communism, if that statement may be interpreted to mean, as I think it can, that no teacher shall even discuss the doctrines of communism.

"Such an interpretation of this provision of the Hart Bill would make it impossible for any teacher in social sciences to discuss or analyze realistically a great many of the most serious problems that we face in the world today."

The Dartmouth, in some excellent editorials, defended true freedom of inquiry at any educational level. In order to illustrate the impact of such legislation upon Dartmouth College, the paper pointed out that "an act prohibiting the teaching of 'Doctrines of Communism,' or overthrow of the government by force has the power to remove from Baker Library every copy of the Communist Manifesto and Das Kapital; it can prevent the reading of Marx and Engels in Great Issues; it can exclude from consideration in history, government or economics everything of the basis, beliefs and practices of communism; it can reduce any course in the history of modern Europe to sheer absurdity."

The author, Mr. Hart, claims that nowhere in the bill exists a prohibition against teaching communism in New Hampshire. However, provision I of this bill reads: "No person shall teach or advocate the doctrines of communism or overthrow of government by force in any public or private school in the state or at the University of New Hampshire That is a clear enough statement of prohibition.

Such a requisite measure as a loyalty pledge would only be a formality in the academic career of a communist teacher. Not uncommonly, the best teachers, sensing this State suspicion, would prefer to relinquish their positions rather than avow their loyalty before a state legislature.

The outcome o£ such legislation, followed by investigations, could only result in legal complications so confusing that "a squad of Daniel Websters couldn't extricate Dartmouth from encroachment by the State."

Why bother with communism, Marx, Engels, Lenin, Lysenko? Why not toss the books out of Baker and the University of New Hampshire? Simply because informed men must make their own evaluations, or risk being misinformed. Understanding is the only weapon, and in classrooms this ideology of historical materialism or communism can be exposed as inept, in its impressive but fallacious concept of man as a mere historical animal.

Deny this understanding to college men who will try to unsnarl the crises of the future and they will work armed with mere half-truths.

The issue of the Hart Bill met such spontaneous resistance at Dartmouth that Representative Hart himself was asked to debate the question, "Are the Hart Bills desirable?"

The Representative and Mr. Fred A. Tilton '28, a lawyer from Laconia, N. H., defended the proposals against the criticism of Government professor Robert K. Carr '29 and Colin L. Raubeson '51, a veteran of five years in the Army.

Enthusiastic students and townspeople, full of liberal comment, heard Mr. Hart assert, "It is not my intention to make an investigation of Dartmouth, the finest school in the U.S." Parents, he said, had complained of a strong communist influence in education.

In ten-minute arguments both Professor Carr and Raubeson tried to point out that state interference with education would constitute a dangerous threat to any truthseeking institution.

An inspiring example of free speech and assembly and the American right to sound off on all issues rather than parrot an imposed philosophy, the forum voiced the danger of communism and agreed that it could not be ignored.

Perhaps Bob Woody '5O of New York City posed the crucial question when he asked, "How do we differentiate between 'teach' and 'teach about'?" Mr. Hart's answer was unsatisfactory.

Following the forum, letters from sincerely worried students crowded into the pages of the paper. Evidently the legislators in Concord were confused on the great issues involved. Nelson Bryant '46 quoted Mr. Hart as saying he didn't see what we were so stirred up about as the bill didn't affect us.

That statement, according to a letter signed "Vox Clamantis," reflects the thoroughness of the consideration afforded this legislation in Concord. The same writer deplores the advent of "thought control" and a democracy "blinded by fear."

Recognizing the seriousness of both situations—communism in education and legislation clamping down on free inquirywhat steps should the colleges themselves take? Should the College take a public stand is a question asked by both students and faculty. If /lot, and this Bill becomes law, do we invite an ordeal similar to that affecting the University of "Washington?

Sidney Hook, Chairman of the Philosophy Department at New York University, discusses the threat of communism to education in the February 28 New York Times Magazine Section in his article, "Should Communists Be Permitted To Teach?"

Academic freedom is vital and has been contested since universities evolved, he says in effect. To censor this freedom defeats the purpose of a university.

However as a communist, under certain conditions of membership, bound by directives from The Communist, an official party organ, a teacher is no longer an agent of free inquiry.

"To stay in the Communist Party, they must believe and teach what party line decrees," he writes. "Anyone is free to leave or join the party, but once he joins and remains a member, he is not a free mind."

Professor Hook points out that public suspicion in the quest for Communists has already injured loyal teachers. Any state legislation could only augment this public defamation. "There is no safer repository of the integrity of teaching and scholarship than the dedicated men and women who constitute the faculties of our colleges and universities," he says.

Dartmouth agrees. Already politics have begun dissecting one U.S. university and more politicians may be inclined to popularize their offices at the expense of a teacher's career. Let the faculty as a whole determine their own course of action.

Passage of the Hart proposals in Concord could mean another Dartmouth College Case.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Article

ArticleTHE ARCTIC

April 1949 By TREVOR LLOYD, -

Article

ArticleConcerning Admissions

April 1949 By H. CLIFFORD BEAN '16 -

Lettter from the Editor

Lettter from the EditorLetter from Oxford

April 1949 By CHARLES G. BOLTE '41 -

Class Notes

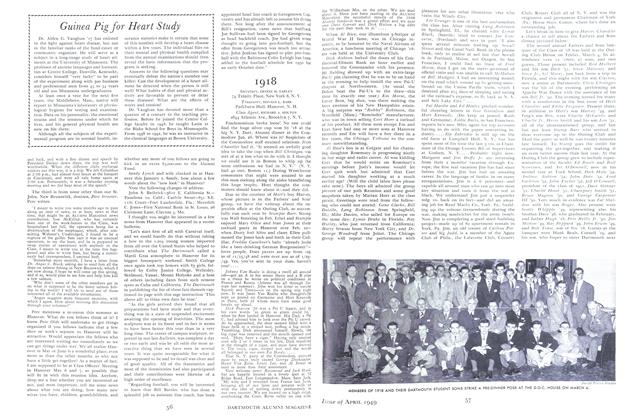

Class Notes1918

April 1949 By ERNEST H. EARLEY, DONALD L. BARR, RICHARD A. HOLTON -

Article

ArticleDeaths

April 1949 -

Class Notes

Class Notes1929

April 1949 By F. WILLIAM ANDRES, EDWIN C. CHINLUND, GEORGE B. REDDING