A FEW WEEKS before the start of the A 1950 football season, Business Manager Irving Smith '41 of the Dartmouth Athletic Council will receive some special requests for press box tickets. These requests will come from universities and colleges listed on the Dartmouth football schedule.

Polite letters will ask for one or two scouting tickets for gentlemen from Michigan, Lehigh, Harvard and other Dartmouth rivals. Just as politely, Smith will acknowledge the requests for press box seats and will mail the tickets.

This is a far cry from the way football scouts operated a few decades ago. Using an alias and perhaps even a disguise, the scout would stealthily spy on an opponent and return with any information that might be of use to his team. If caught by students or alumni of the institution being spied upon, he might be tarred and feathered and sent roughly on his way. Scouts had to operate from open bleachers or hang from trees overlooking the football field.

All of this changed in the mid-1920s when scouting became an accepted part of the autumn mania called football. Scouts began to be welcomed with open arms. Guided to a choice seat in the press box and supplied with lineups, numbers, reams of paper and sharp pencils, the scout was able to work in relative comfort. Consequently, his information became more accurate and his diagnosis of an opponent's methods gave his head coach a reliable indication of what to expect the following Saturday.

Today scouting is an exact process, based largely on the important science of mathematics. Almost all observations by the scout are transmitted to paper in the form of mathematical symbols. A mechanical calculator is needed on his return home to summarize the long columns of figures he has collected on his trip. Once these figures are totaled and placed in their proper places, the scout has the answers to what makes an opponent tick.

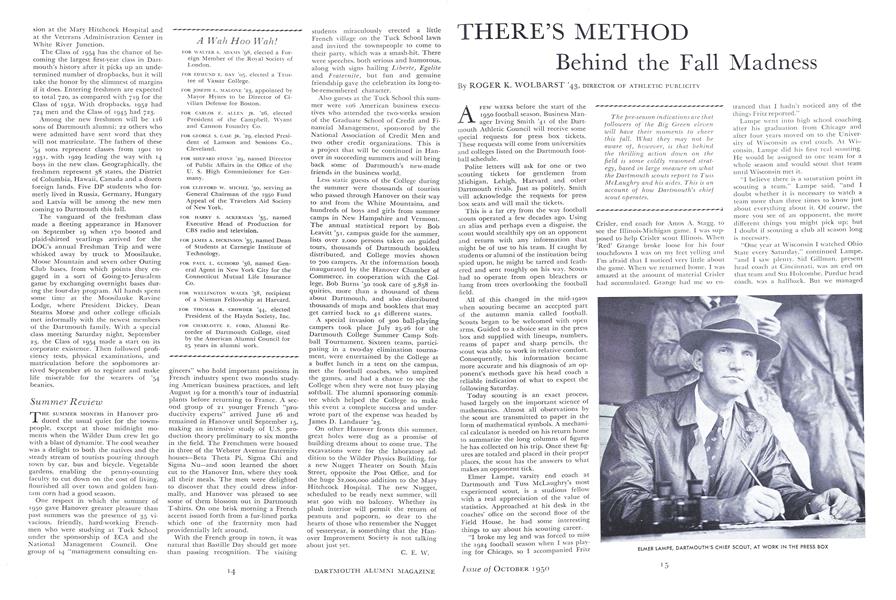

-JTi Elmer Lampe, varsity end coach at Dartmouth and Tuss McLaughry s most experienced scout, is a studious fellow with a real appreciation of the value of statistics. Approached at his desk in the coaches' office on the second floor of the Field House, he had some interesting things to say about his scouting career.

"I broke my leg and was forced to miss the 1924 football season when I was playing for Chicago, so I accompanied Fritz Crisler, end coach for Amos A. Stagg, to see the Illinois-Michigan game. I was supposed to help Crisler scout Illinois. When 'Red' Grange broke loose for his four touchdowns I was on my feet yelling and I'm afraid that I noticed very little about the game. When we returned home, I was amazed at the amount of material Crisler had accumulated. Grange had me so entranced that I hadn't noticed any of the things Fritz reported."

- e> 1 Lampe went into high school coaching after his graduation from Chicago and after four years moved on to the University of Wisconsin as end coach. At Wisconsin, Lampe did his first real scouting. He would be assigned to one team for a whole season and would scout that team until Wisconsin met it.

"I believe there is a saturation point in scouting a team," Lampe said, "and I doubt whether it is necessary to watch a team more than three times to know just about everything about it. Of course, the more you see of an opponent, the more different things you might pick up; but I doubt if scouting a club all season long is necessary.

"One year at Wisconsin I watched Ohio State every Saturday," continued Lampe, "and I saw plenty. Sid Gillman, present head coach at Cincinnati, was an end on that team and Stu Holcombe, Purdue head coach, was a halfback. But we managed to beat Ohio State, so I felt pretty good. However, when you lose to a team that you have scouted, everyone looks for things that went wrong and someone is liable to point a finger at the scout. That balances out the nice feeling you have when you win."

Lampe moved into small college head coaching for several years before joining Wally Butts at the University of Georgia. After eight years at Georgia, Elmer came to Hanover as Tuss McLaughry's end coach in 1946. Incidentally, the first team he ever played against in college was Georgia and his last college game was against Dartmouth.

"That Dartmouth game was something," said Lampe. "Swede Oberlander passed us dizzy and although we had a powerful line, it didn't do us much good. Dartmouth had the first really good passing attack we had ever seen. They were twenty years ahead of their time and we were never able to adjust to those passes."

Lampe's scouting routine at Dartmouth works like this. He is assigned three opponents at the start of the season by Tuss McLaughry. Tuss usually wants to scout each rival three times if it is possible. The scout first goes over the previous year's movies of the opponent and studies old scout reports so he knows what the rival coach's offense is like. Then he keeps a file of newspaper clippings on the opponent to see what individuals are standing out and to get a line on the team's statistical record.

Having left for the opponent's game on Friday, Lampe arrives at the stadium in plenty of time before the start of the contest. He is usually aided in his scouting by a Dartmouth alumnus from the area in which the game is being played. In most cases the alumnus is a former football player. After getting settled in the press box, the scout starts memorizing the numbers of the rival offensive and defensive teams. Having learned the players' numbers, the scout watches the opponent warm up before the game. Lampe says that sometimes one can pick up various characteristics of players during this pre-game drill. Speed, pass-catching ability, punting distances and passing accuracy are a few items that might catch a scout's eye.

The scout brings with him a set of prepared forms giving the basic offensive formations the rival team uses. These sheets list position of the ball, down, yards to go, gain on each play and the defense used by the other team. Throughout the game, with the help of his assistant, the scout charts every play by both teams. Habits and sequences of the scouted team are noted, together with any individual idiosyncrasies of the players.

Following the game, the scout returns home and immediately gets all the offensive and defensive data into statistical form. This material is then presented to Head Coach McLaughry and his assistants. The staff discusses the opponent's offense and defense and goes over methods of stopping the rival attack and splitting the opponent's defense. After hours of discussion, McLaughry then makes the final decision as to what Dartmouth's offensive and defensive plan will be. The scout then makes up more condensed scouting reports for the members of the Dartmouth team to study.

Someone asked Lampe whether he ever scouted a team that was so good that it appeared to have no apparent weaknesses. A team that looked invincible at every position. What does a scout do in a case like that?

"Every team, no matter how good, has some weaknesses," Lampe said. "Take Cornell last year. They could run inside or out, could throw the ball well and had size, speed and great depth. Cornell could have played anyone in the nation and done well. But they had a few weaknesses. Every defense can be exploited by the right plays. And any type of attack can be stopped by the right defenses. That sounds paradoxical, but it's true. Of course, that applies only if the personnel of the scouted team is somewhat similar to your own.

"Our problem is to find the plays that can beat the opponent's defense and instruct our quarterback what to do. Also, it is the scout's job to help the coaching staff discover what defenses will be effective against the opponent's strong attacking phases."

Lampe was then asked if a scout is ever completely fooled by an opposing team. "Sometimes that does happen," he replied. "Every so often a team will use an entirely different attack for one special game. A single-wing team may practice T-formation plays all season long but never use them until a climactic point in the season. Naturally, if a scout reported on a team's single-wing offense and in the game against his team it used the T-formation, the scout would have been useless.

"But most teams stick to what they know best and use that system right along. Special plays are rarely saved all season lor a particular opponent any more. Most teams practice a certain type of attack and modify it for each new type of defense that is met."

On each succeeding Saturday the Dartmouth scout is again perched high in the press box busily watching another opponent in action. He wonders how the Big Green is doing and keeps sending messages to the Western Union operator nearest him to try to find out the Dartmouth score.

Lampe was scouting Harvard a year ago when the score of the Dartmouth-Colgate game came in at halftime. The loudspeaker announced, "Colgate 6, Dartmouth o, at the half." Lampe says, "I heard that score and I was ready to take up ploughing. I worried all through the second half until I heard the final score, Dartmouth, 27; Colgate, 13. Then I felt human again. I decided that maybe I would stick to coaching and scouting for a while longer.

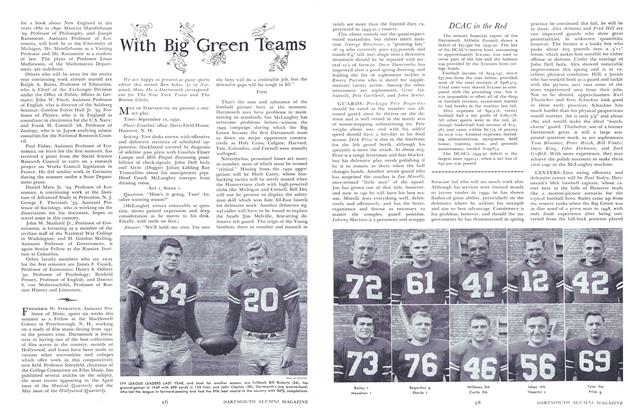

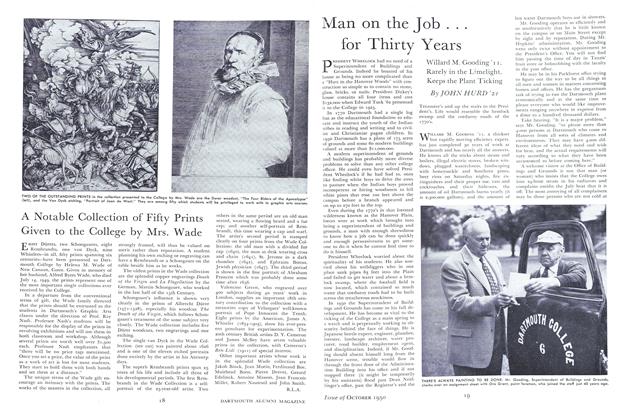

ELMER LAMPE, DARTMOUTH'S CHIEF SCOUT, AT WORK IN THE PRESS BOX

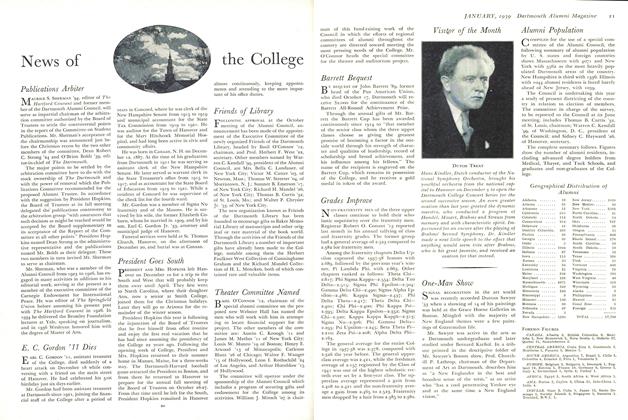

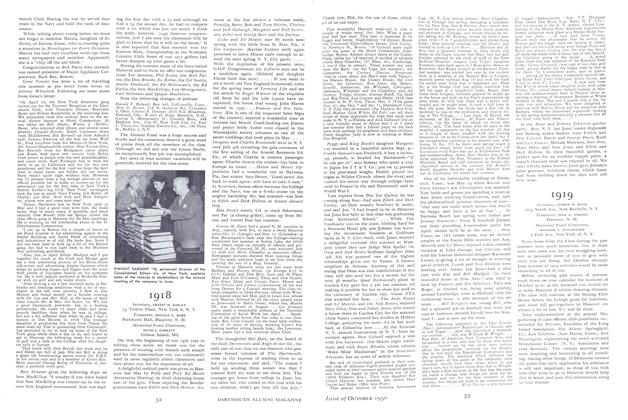

WITH HIS SCOUTING REPORT on a Big Green opponent presented in a statistical nutshell on the black- board in the coaches' office, Elmer Lampe goes over his findings with Head Coach Tuss McLaughry (center) and Backfield Coach Milt Piepul preparatory to devising offensive and defensive strategy for the game.

The pre-season indications are thatfollowers of the Big Green elevenwill have their moments to cheerthis fall. What they may not beaware of, however, is that behindthe thrilling action down on thefield is some coldly reasoned strategy, based in large measure on whatthe Dartmouth scouts report to TussMcLaughry and his aides. This is anaccount of how Dartmouth's chiefscout operates.

DIRECTOR OF ATHLETIC PUBLICITY

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Sports

SportsFINIS

October 1950 By Bernard G. Sykes '51 -

Article

ArticleMan on the Job . . . for Thirty Years

October 1950 By JOHN HURD '21 -

Class Notes

Class Notes1918

October 1950 By ERNEST H. EARLEY, DONALD L. BARR, DAVID L. GARRATT -

Class Notes

Class Notes1923

October 1950 By TRUMAN T. METZEL, COLIN C. STEWART 3RD, JULIUS A. RIPPEL -

Class Notes

Class Notes1905

October 1950 By GEORGE W. PUTNAM, GILBERT H. FALL -

Class Notes

Class Notes1949

October 1950 By ROBERT H. ZEISER, DAVID S. VOGELS JR.